Soldiers of the 1st Infantry Division in their M1A1 Abrams tank in Iraq, April 2004.<a href="http://usarmy.vo.llnwd.net/e2/-images/2007/04/22/3579/">Photo by Pvt. Brandi Marshall</a>/US Army

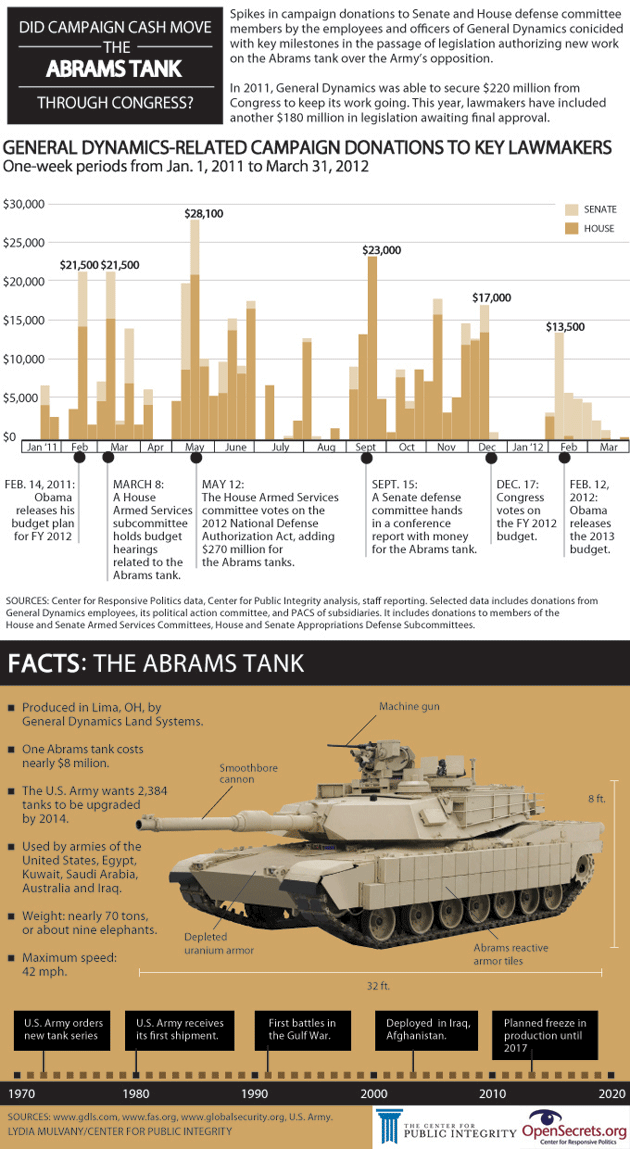

The M1 Abrams tank has survived the Cold War, Iraq, and Afghanistan. No wonder—it weighs as much as nine elephants and is fitted with a cannon capable of turning a building to rubble from two and a half miles away.

But now the hulking, clanking machine finds itself a target in an unusual battle between the Defense Department and lawmakers who are the beneficiaries of large donations by its manufacturer.

The Pentagon, facing smaller budgets and looking towards a new global strategy, has decided it wants to save as much as $3 billion by not doing scheduled “refurbishing” upgrades on the tank from 2014 to 2017, and instead redesign the Abrams from top to bottom. But the proposal is fiercely opposed by Abrams manufacturer General Dynamics, which has pumped millions of dollars into congressional elections over the last decade. The tank’s supporters on Capitol Hill say they want to save jobs—the Pentagon’s proposal would idle a large factory in Lima, Ohio, and halt work at subcontractors in several other states—and protect America’s military capability.

So far, the contractor is winning, after a well-organized campaign targeting lawmakers on four key committees that will decide the tank’s fate, according to an analysis of spending and lobbying records by the Center for Public Integrity.

Sharp spikes in General Dynamics’ donations—including a two-week period in 2011 when its employees and political action committee sent the lawmakers checks for their campaigns totaling nearly $50,000—roughly coincided with committee hearings and votes on the Abrams.

Last year, both the House and Senate restored the tank money the Pentagon wanted to cut from its own budget—and the Armed Services committees in both houses have proposed doing so again this year, to the tune of $181 million in the House and $91 million in the Senate.

The Army already has more than 2,300 M1s deployed with US forces around the world and roughly 3,000 more sitting idle and unneeded in long rows outdoors at a remote military base in California’s Sierra mountains. If Congress restores the money, tax dollars will be going to upgrade about 70 tanks a year—or, as Army chief of staff Ray Odierno put it in a March hearing, “280 tanks that we simply do not need.”

The $3 billion in savings from freezing the refurbishments is not a large sum in Pentagon terms—it’s what the department spends in a little more than a day. But the fight over the Abrams’ future illuminates the pressures that drive the defense spending debate: The Pentagon is looking to free itself from legacy projects and modernize some of its combat strategy, Congress is determined to defend pet projects, and a well-financed defense industry is fighting to fend off even small reductions in the budget devoted to the military—which composes about half of the federal budget’s discretionary spending.

Vulnerable to IEDs But Impervious to Pentagon Budgeteers

The M1 Abrams entered service in 1980, but first saw combat during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. That experience suggested that, on the battlefield at least, one of the only things that could destroy an Abrams was another Abrams; only seven of the tanks deployed in the operation were destroyed, all by friendly fire.

In the last decade, however, as hundreds of the vehicles were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, a key shortcoming became apparent: The Abrams’ design made it vulnerable to improvised explosive devices (IEDs). As a result, the Abrams in Iraq sometimes ended up being used as “pillboxes”—high-priced armored bunkers used to protect terrain rather than go out and patrol.

“The M1 is an extraordinary vehicle, the best tank on the planet,” says Paul D. Eaton, a retired Army major general now with the nonprofit National Security Network. But its utility in modern counterinsurgency warfare is limited, he adds, because the tank’s primary purpose is to kill other tanks—as it would have in the kind of combat envisioned during the Cold War.

Ashley Givens, a spokeswoman for the Army’s Program Executive Office for Ground Combat Systems, said that the Army can get all the refurbishing it needs done by the end of 2013. Freezing work after that, she said, will allow it to “focus its limited resources on the development of the next generation Abrams tank,” rather than the current model that has “exceeded [its] space, weight, and power limits.”

Nonetheless, top Army officials have been unable to get political traction to kill the M1—thanks in large part to General Dynamics’ checkbook. Since January 2001, GD’s political action committee and the company’s employees have invested $5.3 million in current members of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees or defense appropriations subcommittees, according to data the Center for Public Integrity acquired from the Center for Responsive Politics.

Kendell Pease, GD’s Vice President for Government Relations and Communications, told us that the company—which produces submarines and radios for the military, as well as tanks—makes donations to lawmakers whose views are aligned with the firm’s interests. “We target our PAC money to those folks who support national security,” Pease says. “Most of them are on the four [key defense] committees.”

But Pease denies trying to time donations around key votes, saying that the company’s PAC typically gives money whenever members of Congress invite its representatives to fundraisers. “The timing of a donation is keyed by [members’] requests for funding,” he says, adding that personal donations by company employees are not under his control.

More Cash at Key Milestones

During the current election cycle, General Dynamics’ political action committee and its employees sent an average of about $7,000 a week to members of the four committees. But the week President Obama announced his defense budget plan in 2011, the donations spiked to more than $20,000, significantly higher than in any of the previous six weeks. A second spike of more than $20,000 in donations occurred in early March 2011, when Army budget hearings were being held.

At a March 9 hearing of the House subcommittee dealing with land forces, Rep. Silvestre Reyes (D-Texas) railed against the Army’s decision to freeze work on the Abrams. Since the start of 2001, Reyes has received $64,650 in GD donations, including $1,000 on March 10, the day after the hearing, according to the data. Reyes’ office did not respond to a request to comment.

Another large spike came in May 2011, when the House Armed Services Committee voted 60-1 for a budget bill containing money to continue work on the Abrams through 2013. Over this period, GD’s PAC and employees donated a total of $48,100 to members of the four committees, with almost $20,000 of that going directly to members of the House Armed Services Committee.

During another two week period in September, in which the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense handed in its conference report and Congress rushed to pass a stopgap spending bill to keep the government open, the company sent $36,500 to members of the committees—primarily the House Armed Services Committee, whose members got $30,500.

The final large spike in donations last year came the week of December 11-17, when Congress voted on the whole Pentagon budget. During this week, GD’s donations to members of the four committees totaled $17,000.

Along with its checks, the company has been delivering a message that a cutoff of tank manufacturing work in Lima will harm the nation’s “industrial base”—a favorite expression for military contractors facing cutbacks.

The workforce “is not like a light switch. You can’t just click it off, then walk away for three years, come back and click it on,” Pease said. GD has also accused the Army of underestimating the cost of idling the Lima plant, claiming that the government’s actual savings would be minimal.

To drive these points home, General Dynamics has spent at least $84 million over the past 11 years on lobbyists, according to Senate Office of Public Records lobbying data acquired from the Center for Responsive Politics. While lobbyists often do not name their causes, those working for GD that specifically listed the Abrams tank, along with other topics, reported earning at least $550,000 from 2011 to the first quarter of 2012, according to the data. Pease described the lobbying efforts as “education…Shame on us if we don’t go and tell them [Congress] our side.”

Relying on Special Contacts

In addition to tapping its in-house team, the company hired outside firms that assigned the General Dynamics account to former congressional staff and others tightly connected to committee members. GD has paid the Podesta Group, run by famed Democratic lobbyist Tony Podesta, more than $1.5 million since 2009 to lobby on the defense appropriations and authorizations bills, according to lobbying disclosure forms. Among the more than 20 Podesta lobbyists assigned to the account was Josh Holly, communications director for the House Committee on Armed Services under Republican leadership for six years.

According to Holly’s bio on the Podesta website, on the Hill he worked directly with California Republican Buck McKeon, the committee’s current chairman. McKeon has received $56,000 from GD’s PAC and employees since 2009, when he became the committee’s top Republican. Holly did not respond to emails and phone calls seeking comment, and committee spokesman Claude Chafin said McKeon has consistently argued that it is fiscally smarter to keep the Abrams work going than to stop it.

Podesta also assigned the GD account to two former House Appropriations Committee aides. One of them, Jim Dyer, confirmed that he lobbied on the tank this year, but he directed other questions to General Dynamics. GD also hired firms that assigned its account to six other lobbyists who once worked for the relevant committees, and to a former Pentagon official who had served as the department’s liaison to Congress.

Pease said that when working with outside firms, he lets them choose the specific lobbyists on the account. But when picking the firms, “you always look for those people who can get the job done,” he says.

So far, it seems the job has been getting done—earlier this year, 173 members of Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, signed a letter of support for the tank. But their support isn’t necessarily in full public view.

Both this year and last year, the Abrams funds were added to the Pentagon budget without a specific recorded vote—in other words, as modern day earmarks. Earmarks were supposed to have been banned after the 2010 election, but lawmakers have decided that when multiple members favor adding funds—rather than just one lawmaker—it is not formally an earmark.

Rep. Jim Jordan, who represents the Ohio district where the Lima plant is located and has received $31,000 for his campaigns from General Dynamics’ leadership PAC and employees, said he is now optimistic that the Abrams money will make it safely through the Senate.

If it does, the fight still might not be over. The White House, in its May 15 response to the House budget, objected to the “unrequested authorization” of funds for the Abrams during a “fiscally-constrained environment.” The administration did not specifically threaten a veto over the issue but said that if too many unrequested projects impeded “the ability of the Administration to execute the new defense strategy and to properly direct scarce resources,” senior advisers will recommend the president veto the bill.

Reporter Zach Toombs and Data Editor David Donald contributed to this report.

Reporter Zach Toombs and Data Editor David Donald contributed to this report.

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit, independent investigative news outlet.