Iwaki city, one of the most damaged areas in Fukushima.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/fuuasumma/5720939326/">fuuasumma</a>/Flickr

This story first appeared on the Guardian website.

It’s little wonder that Chieko Sasaki is gripping two bottles of sake like her life depends on it.

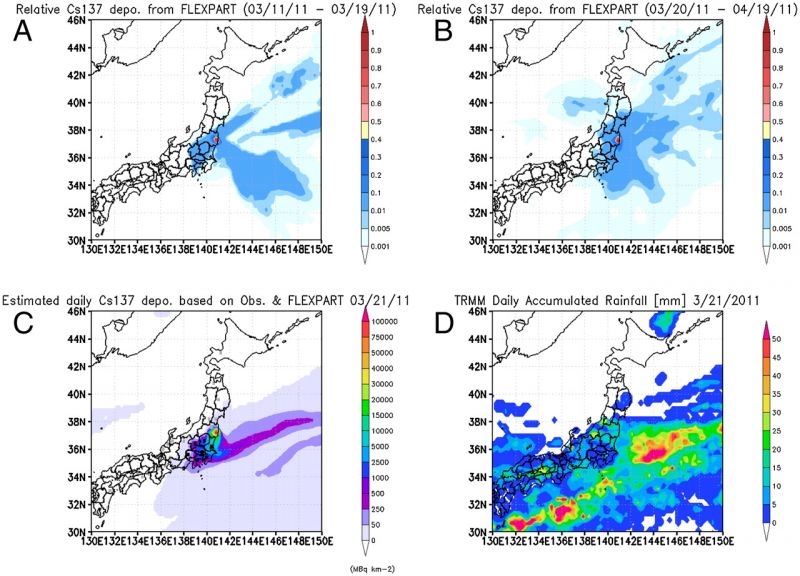

For weeks after the meltdown at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant last March, Sasaki believed her brewing business had met the same fate as her hometown, Iitate.

The farming village lies just outside the 20km (12-mile) evacuation zone surrounding the plant, but was evacuated two months after the accident after independent monitors discovered dangerously high levels of radiation there.

Sasaki, along with 7,000 Iitate residents, left the home she shared with her husband, son and grandson, and said a quiet farewell to her brewery, restaurant and the fields where she once grew organic rice and vegetables.

“When I think about my old house, I get a headache and can’t sleep,” she said. “I took out millions of yen in loans to build my old brewery and restaurant, and I was on the verge of paying them off when the accident happened.

“Then I had to borrow more money to open this place. Tokyo Electric Power [the operator of the plant] has paid me some compensation, but it’s a drop in the ocean.”

Almost a year and half later, Iitate’s residents, now scattered around the region in temporary shelters and private accommodation, still don’t know when they will be able to make a permanent return, although many are now permitted to visit during daylight hours.

The uncertainty, and boredom with life as a nuclear evacuee, drove Sasaki, 66, to resurrect her business making unrefined doburoku sake at her new premises just outside Fukushima city.

Standing in her way was a web of red tape. Japan’s brewing laws are weighted in favour of large-scale producers, and Sasaki had only been given permission to brew the doburoku, which requires a special license, after Iitate was granted special economic status in 2006.

As soon as she was evacuated, she effectively lost her right to work. Under pressure from the Iitate council, the authorities compromised, and Sasaki began brewing again with the last batch of the village’s rice harvest from 2010.

Last year’s crop was never harvested due to fears over radiation, but what little was left of the previous year’s supply went towards the production of six large barrels of sake, with the final product going on sale in May. From this year, she will use rice grown by relatives living in another part of Fukushima prefecture.

“I made far less than I used to,” she said. “I used to sell huge amounts for New Year’s celebrations, summer festivals and social events. But now my old neighbours are scattered all over the place.”

Sasaki has returned to her old routine of visiting her brewery three times a day to monitor the sake’s temperature. But her enthusiasm is tempered with resentment at the hand the nuclear accident has dealt her and her family.

She visited her former home last winter to find that the bath, sink and toilet had cracked irreparably, and layers of ice on the floor where water had leaked through the roof. There were signs that wild animals had invaded the property.

“I can’t think about the future at all,” she said when asked about official promises that parts of Iitate could be inhabitable within two years.

But after word spread about her sake venture, Sasaki quickly found herself running out of stock as old neighbours and new customers indulged their love of her cloudy, slightly fizzy tipple.

“If this can help lift people’s spirits even just a little, then I’m happy to do whatever I can to help.”