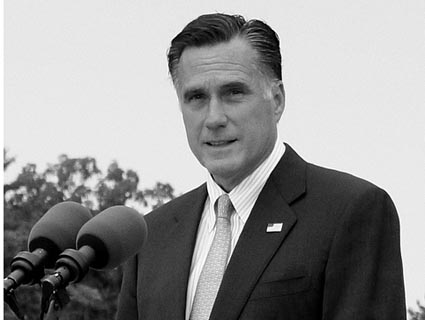

Michal Fludra/Newspix/ZUMA Press

With Mitt Romney the presumptive GOP presidential nominee, his wife, Ann, has become the most high-profile advocate for people with multiple sclerosis since Mouseketeer Annette Funicello. From her new post as potential first lady, Ann Romney has done much to raise the profile of an incurable, degenerative illness that afflicts some 400,000 Americans. Local chapters of the National MS Society have been clamoring for her to appear at their fundraisers and other events.

But there’s a problem: MS advocates say that policies Romney now supports would be detrimental for many MS sufferers, and they are actively opposing these proposals. Which means that Mitt Romney is now at odds with the MS community he and his wife have long supported.

Earlier this year, Mitt and Ann made a short video called “Soul Mate” for his presidential campaign in which they talked about what it was like in 1998 when Ann was diagnosed as having the degenerative nerve disease. “Probably the toughest time of my life,” Mitt said. The campaign video ended with a pitch for people to donate to the National MS Society.

National MS advocates are appreciative of Ann Romney’s efforts to help boost the profile of the disease and raise money for the cause, but they are opposing her husband’s campaign health care policy proposals, many of which are mirrors of GOP legislation currently pending in Congress. MS advocates believe many of the proposals would be extremely harmful to most people with multiple sclerosis.

“To the degree that Mrs. Romney brings attention to the disease, that’s extremely positive,” says Ted Thompson, the vice president for federal government relations at the National MS Society in Washington. But he acknowledges that her husband’s health care platform is not helpful.

“The contradiction has been pointed out to us,” he says judiciously.

Romney has pledged to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. He also would turn Medicaid, the government health care plan for children and the poor, into a block grant, a plan that would ultimately cut millions from the program. And when he promises to replace Obamacare, Romney has offered only a few weak substitutes, such as capping damages in malpractice lawsuits. All of this would have tremendous implications for people with multiple sclerosis.

The MS Society is actively opposing the repeal of Obamacare, which it enthusiastically supported (just as it did with Romneycare in Massachusetts). “There are so many provisions in the health law that are beneficial to people with chronic illness, including MS,” Thompson says. “To do a wholesale repeal would be a real setback. MS is a very expensive disease to have, unlike cancer, where you either get cured or pass away.” He explains that MS can cost sufferers about $70,000 a year, half of which is attributed to medical costs. That’s one reason why the new health care law is so critical to people with MS: The law ends lifetime limits on insurance coverage, which someone with MS can quickly burn through.

The new law also has a host of measures that will help people with chronic illness live better lives. It includes requirements that insurers sufficiently cover habilitation services, which include physical and occupational therapy and other measures that can help slow the progression of chronic diseases and keep people in the workforce and out of government programs. Thompson says that requiring coverage of those services is “not only the right thing to do, but it saves money because we’re not letting the disease deteriorate so quickly.”

The MS Society also strongly opposes block-granting Medicaid, which would turn the federal program over to the states to run on a fixed allocation from Washington. Romney sells his plan as a way of allowing states to innovate. But block grants are a form of stealth budget cut. A similar move in the welfare program in the mid-1990s has resulted in a 30 percent reduction in the amount of money the country now spends on cash assistance to poor single mothers. Cuts to Medicaid could seriously imperil people with MS, Thompson notes. MS is such an expensive disease that the high medical costs, combined with the associated disability that often forces people out of the workforce, can leave middle-class sufferers deeply impoverished and forced to rely on Medicaid. “The reason they’re on Medicaid is that they may have slipped into poverty because of the illness.” Thompson says. “It’s through no fault of their own,”

Mitt Romney’s opposition to policies embraced by the MS community comes after years of Ann Romney publicly advocating on behalf of people with MS. From 2004 through 2007, she served on the board of trustees of the Greater New England chapter of the MS Society, while her husband was governor of Massachusetts. In that position, she lobbied the Massachusetts statehouse for the society’s legislative agenda, which included proposals for state funding for health care and disability programs and the society’s Home LINKS program, a public-private partnership that provides case management services to people with MS. Ann helped press legislators for improved long-term care services, better access to prescription drugs for Medicaid beneficiaries, and a host of other issues designed to assist people with disabling chronic conditions like MS.

Steve Sookikian, the associate vice president for communications at the Greater New England chapter of the MS Society, collaborated with Romney regularly during her time on the board. “She was wonderful to work with,” he says, “ready to share her experience of personally living with MS.” Ann attended a number of activities sponsored by the chapter and made herself available for publicity to generate awareness for MS. Romney was a committed advocate who could be counted on to make the 70- or 80-mile drive from home in time to show up at 7 a.m. on Cape Cod to kick off the chapter’s annual 50-mile fundraising walk.

Sookikian says that for several years Ann helped launch the MS chapter’s annual lobbying day at the statehouse with a motivational speech. At one of those events, Ann recounted her interaction with her husband that morning. Mitt had noticed she was getting dressed up and asked, “Where are you going?” She replied, “To the statehouse.” When Mitt asked why, Ann exclaimed, “To lobby you!”

The Greater New England MS chapter’s 2006 annual report featured a photo of Gov. Romney signing a bill supported by the society to create a commission to study the needs of young adults with chronic disabilities, with the goal of expanding long-term care options for them. The law also required the state’s regional transportation authorities to include disabled people on their boards, to ensure that the needs of the disabled were included in transportation planning.

Linda Guiod, the chapter vice president for programs, services, and advocacy who also worked closely with Ann Romney, says, “The governor was never openly opposed to any of our legislative issues…Whenever our bills were approved by the Legislature, he signed them.” And the chapter backed Romneycare because it helped guarantee, among other things, that people with chronic illnesses could obtain affordable insurance and could not be discriminated against by insurers for preexisting conditions.

That was then.

The MS Society is not a partisan political operation—its nonprofit status bars it from getting involved in presidential campaigns or endorsing candidates—but there’s no doubt that privately, individual MS advocates would be overjoyed at the prospect of having the spouse of a leading supporter become president of the United States. A first lady with MS could do wonders for their cause—everything from pushing for better medical research on the disease to making sure that the chronically ill and disabled aren’t an afterthought in major policy battles.

But in this case, the MS community has good reason to root for the other team. MS advocates could well face the possibility of having to use money the Romneys helped them raise to fight a President Romney’s attempts to kill policies and programs they need to survive.