<a href="http://patrickmurphy2012.com/video">Patrik Murphy for Congress</a>

Everyone wants a piece of Patrick Murphy. “I was hoping to have a walk-and-talk with you,” the 29-year-old Florida congressional candidate tells me, “but Charlie Crist just called and told me he wants to meet.”

Murphy, a businessman and former Republican, became a Democrat last year. He is meeting with Crist, the former governor of Florida and a fellow ex-Republican, at the Westin on the other side of the security perimeter in Charlotte. Then it’s off to a meeting with New York Rep. Steve Israel, head of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, which has anointed Murphy as part of its “red to blue” program for top recruits. Murphy has already met with House Minority Whip Steny Hoyer (D-Md.), DNC Chair Debbie Wasserman-Schultz (D-Fla.), and a group of Jewish Democrats. He’s swamped, waiting anxiously for his blue SUV as he gland hands with Florida delegates outside the Marriott. “Basically there was more than I can go to,” he says, “so at some point it’s just saying, ‘What can I make it to without having to walk like five miles through the rain?'”

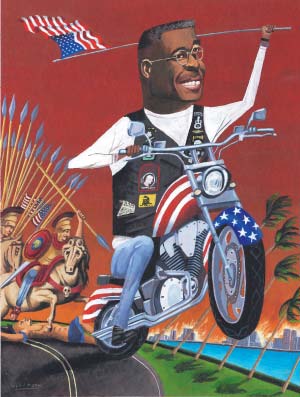

There’s a reason Murphy is a popular guy in Charlotte: He’s taking on Rep. Allen West (R-Fla.), the first-term congressman famous for accusing progressive colleagues of belonging to the Communist Party. West, a tea party icon, has accused Democrats of keeping African Americans “on the plantation,” compared himself to Harriet Tubman, and, most recently, called Dems “the most racist party I’ve ever seen in my life.” (As of Wednesday, West is also a national co-chair of Mitt Romney’s black outreach initiative.) Democrats need to flip 25 seats to take control of the House of Representatives. President Obama needs a big win in Palm Beach County if he wants to win Florida. West and Murphy’s 18th congressional district is where the action is.

“Just, half of his comments I just don’t understand,” Murphy says of his opponent. “They do not make”—he pauses for a moment—”sense. They’re irrational, unreasonable, untrue.”

Eight weeks from Election Day, polls show the race deadlocked. Murphy believes the selection of Paul Ryan as Mitt Romney’s running mate and Todd Akin’s victory in the Missouri Senate primary have given him an opening to prove that West, who has claimed to be a warm-and-fuzzy moderate in campaign ads, is a radical.

“They’ve just gone so far off the deep-end,” Murphy says. “Truly, if more people read the platform, I feel that they’d also change parties. Whether it’s gun rights, whether it’s reproductive rights, it’s so extreme right now. Most people don’t realize, that my sister-in-law, for example, is a Republican. And we were talking about Todd Akin and she said, ‘Oh, he’s just a crazy guy! That’s just an exception.’ I said, ‘Listen, that’s not just an exception, that’s the rule now. It’s in the platform. There are no exceptions. It’s the rule now!'”

“I had to give an interview…a reaction to Paul Ryan’s speech, and I was shocked by what he was saying,” Murphy says, referring to Ryan’s debunked claims about Medicare. “I just kept circling the word ‘lie.’ Lie, lie. Do they think Americans are not gonna pay attention?” West, who has sought to present himself as a defender of the social safety net in ads, has previously referred to Social Security as “slavery.”

Whether the strategy of tying West to the national GOP will work remains to be seen. West has been a congressman for two years and a candidate for four. If voters weren’t already convinced that he is a bit out there, it’s not clear why tying him to a Senate candidate from Missouri and a vice presidential hopeful from Wisconsin would change their minds.

And Murphy, a newcomer to the party who doesn’t hesitate when I ask if he’d support a hypothetical Crist comeback (“Yeah, I would”), has taken some lumps of his own. In August, a new super-PAC, American Sunrise, launched a television salvo against West depicting the congressman with a gold tooth and boxing gloves, punching out women and working families. The founder, organizer, and top donor to American Sunrise is Murphy’s father, Thomas, a construction firm CEO. The elder Murphy gave the group $250,000 in seed money in May.

Murphy says he hasn’t discussed the super-PAC with his father. But, he adds, “He’s still my dad. I talk to him about family issues, I talk to him about work, I talk to him about the different things you talk to your dad about. The campaign—and what he does—we just don’t talk about.”

“I’m completely against Citizens United,” he says. “I think the money in politics is ruining the system and we have to change it. Of course, I have no control over what super-PACs are saying or doing. So that’s unfortunate. It’s scary for all of us, as Republicans and Democrats. I hope more Americans wake up and realize that and if Mitt Romney is elected he’ll be able to appoint one or two more Supreme Courts justices, and the implications of that. It’s unfortunate, but super-PACs are out there.”

In the meantime, money matters. And that’s why Murphy is in Charlotte this week, mingling with Democratic big-shots instead of pounding the pavement in West Palm Beach. “Look, Allen West has gotten support from people all over the country,” he says as he heads off for his summit with Crist. “If we are going to beat him, and when we beat him, it’s going to be because of support from around the country. We’ve got to make this a national campaign. Fighting fire with fire in a sense. We’ve got to do the same thing.”

Watch our

Watch our