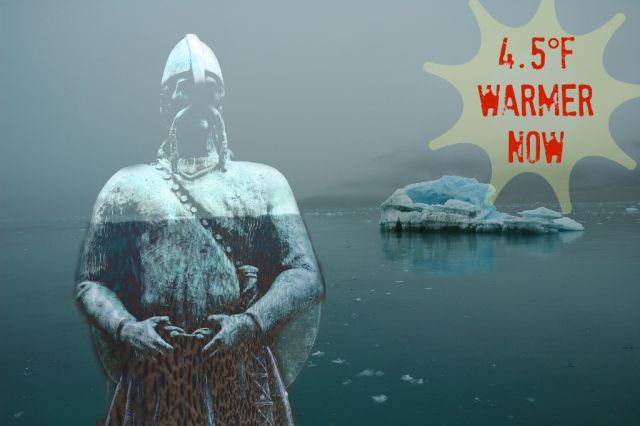

Summers on Svalbard are up to 4.5°F (2.5°C) hotter than during the warm period when Vikings colonized Greenland and Iceland: Svalbard landscape: Wen Nag (aliasgrace) via Flickr. Viking statue: frankdouwes via Flickr. Mashup: Julia Whitty (thanks PicMonkey!)

Summers on Svalbard are up to 4.5°F (2.5°C) hotter than during the warm period when Vikings colonized Greenland and Iceland: Svalbard landscape: Wen Nag (aliasgrace) via Flickr. Viking statue: frankdouwes via Flickr. Mashup: Julia Whitty (thanks PicMonkey!)

Things are so hot on the Norwegian Arctic island of Svalbard these days that if the Vikings were still around they’d flee north to get away from their own sweat. Okay, that’s total conjecture. But a fascinating new paper in the science journal Geology describes how much hotter it is on Svalbard now than it was during the Medieval Warm Period when Vikings colonized Greenland and Iceland and briefly Newfoundland.

The Medieval Warm Period was driven by a natural increase in solar radiation that warmed parts of the northern hemisphere and severely dried out others (California, Nevada, Mississippi Valley). The current warming is driven by us.

The authors used a novel method to decipher temperatures on Svalbard for the past 1,800 years based on the fatty remains of microscopic algae left behind in Kongressvatnet lake. Turns out the algae are miniature record-keepers extraordinaire because they make more unsaturated fats in colder water and more saturated fats in warmer waters, reports the Earth Institute at Columbia University.

The researchers then dated the sediments based on grains of glass spat from volcanoes hundreds of miles away in Iceland: Snæfellsjökullin volcano in the year 170, Hekla in 1104 and Öræfajökull in 1362. How cool is that detective work?

The big difference with the new research is that most Arctic climate records come from ice cores that tell of winter snowfalls. The lake sediments record summertime temperatures. Which reveals a lot about how climate varied from winter to summer and also in places where there are no (longer) ice sheets.

Based on the new summertime story, here’s some of what the authors learned:

- The region was not particularly cold during another recent anomalous period: the Little Ice Age of the 18th and 19th centuries when Svalbard glaciers grew to their greatest extent of the past 10,000 years (and when glaciers in much of parts of Western Europe grew too).

- This suggests that a wetter climate (more snow) rather than colder temperatures may have fed the Svalbard glaciers.

- By 1600 Western Svalbard had begun to gradually warm as the northern arm of the Gulf Stream (the West Spitsbergen Current) brought more tropical water to the region.

- In 1890 the warming began to accelerate.

- Meanwhile ice cores from Svalbard tell a different wintertime story: a slight cooling over the last 1,800 years.

- The conflicting evidence suggests that temperatures may have fluctuated sharply between winter and summer.

From the Earth Institute at Columbia University:

Climate models suggest that by 2100 Svalbard will warm more than any other landmass on earth, due to a combination of sea-ice loss and changes in atmospheric and oceanic circulation… In a study published last year in the journal Advances in Meteorology, Norwegian researchers estimate that average winter temperature in Svalbard could rise by as much as 10 degrees C or 18 degrees Fahrenheit [by 2100].

This video from lead author Billy D’Andrea, a research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, describes the scientific motivations behind his work.

The paper:

-

William J. D’Andrea, David A. Vaillencourt, Nicholas L. Balascio, Al Werner, Steven R. Roof, Michael Retelle and Raymond S. Bradley. Mild Little Ice Age and unprecedented recent warmth in an 1800 year lake sediment record from Svalbard. Geology (2012). DOI:10.1130/G33365.1