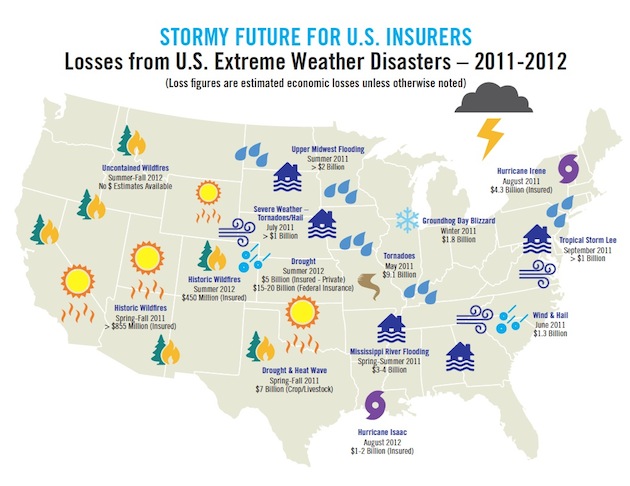

Not a pretty picture.Source: Ceres

When it comes to grappling with the effects of climate change, insurance companies could be on the verge of failing the very people they’re meant to protect.

According to a new report from Ceres, a sustainability-minded business nonprofit, the insurance industry has been relying on deflating financial reserves while being struck with record catastrophe damages—last year, the United States suffered an estimated $55 billion economic loss due to severe weather damages alone, and the $44 billion paid in insured losses for weather and catastrophes was the highest since the year Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast. Meanwhile, the industry’s pricing models still follow outdated risk assessments, lacking plans for more extreme scenarios. The report argues that insurance companies’ inability to adapt to current climate reality could result in unaffordable rates, loss of coverage where it’s needed most, or force government into the role of last resort insurer, which would place more burden on taxpayers.

Sharlene Leurig, one of the report’s co-authors, believes the insurance crisis that’s plagued hurricane-prone Florida, for example, could play out on a national scale. When private insurers hiked their rates or simply pulled out of the area due to frequency of disaster, state-run insurance stepped in, providing cheap, subsidized premiums that encouraged development in vulnerable coastal areas. “The only way Florida was able to fuel its real estate boom was because of cheap insurance,” Leurig told Mother Jones. But, “when the next Hurricane Andrew hits Florida, is there actually going to be insurance waiting for them?

It’s an anxiety-inducing scenario, especially when the National Flood Insurance Plan—though newly-reformed as of this summer—is already $18 billion in debt. But, as extreme weather is demonstrating, floods aren’t the only problem, and most insurance companies aren’t jumping at the opportunity to model new risk assessments with this in mind.

“If insurance companies continue to pursue the risk management strategies that they have in recent years, where they either move out of certain geographies because they’re too risky, or if insurers start cutting out sources of losses that their policies will cover, then what you have is either effectively the loss of any kind of insurance coverage, or you have the potential for risk pools to start expanding,” Leurig explains. “And that’s a very significant risk—to taxpayers, to customers, to consumers, and to the industry itself.”

One of the report’s more troubling hypotheses is already playing out. With more than half the US experiencing severe drought, breadbasket crops are shriveling up. For the majority of farmers who take out federal weather insurance, the government subsidizes those premiums—and for the insurers that provide private policies, the government provides reinsurance. That means that with this year’s droughts, which scientists tie to climate change, public payout in taxes could be upwards of $9 billion, more than quadruple what it was a decade ago.

Leurig argues that in this critical moment, the insurance industry should be aggressively lobbying for updated building codes, better federal policies, and reducing carbon emissions.

Yet in some legislatures, policy-making seems headed towards the exact opposite: This past summer, North Carolina made it illegal to anticipate accelerated sea level rise when setting insurance rates and planning development. The good news is that this policy comes free—until an extremely rainy day.