Mitt Romney isn’t just downplaying his signature accomplishment as governor of Massachusetts, he’s developed a sudden amnesia about the policy problems that lead him to implementing it.

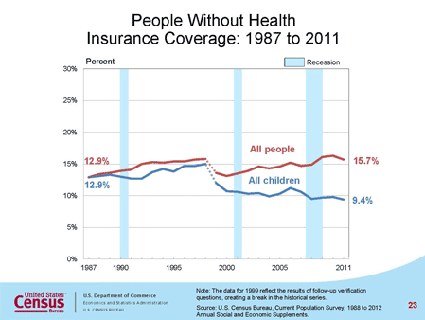

During a 60 Minutes interview on Sunday, CBS’ Scott Pelley asked Romney: “Does the government have a responsibility to provide health care to the fifty million Americans who don’t have it today?”

Romney responded: “Well, we do provide care for people who don’t have insurance, people—we—if someone has a heart attack, they don’t sit in their apartment and and die. We pick them up in an ambulance, and take them to the hospital, and give them care. And different states have different ways of providing for that care.” Romney later repeats usual refrain that what worked for Massachusetts won’t necessarily work everywhere else.

As Maddowblog’s Steve Benen points out though the “emergency room care” line is a go-to talking point for conservatives, this kind of last-resort care raises costs for everyone else and simply doesn’t provide the kind of treatment that really sick people need. Romney knows this—at least he did.

As Sam Stein and Amanda Terkel at the Huffington Post note, Romney recognized this as recently as 2010, when he said on MSNBC’s Morning Joe: “It doesn’t make a lot of sense for us to have millions and millions of people who have no health insurance and yet who can go to the emergency room and get entirely free care for which they have no responsibility.”

This isn’t just a minor point: It’s one of the major reasons both the Massachusetts health insurance law and the Affordable Care Act include an individual mandate. In Romney’s memoir, No Apology, he calls the realization that emergency room care substantially raises costs an “epiphany.” From page 171 (italics original, bolded mine):

After about a year of looking at data—and not making much progress—we had a collective epiphany of sorts, an obvious one, as important observations often are: the people in Massachusetts who didn’t have health insurance were, in fact, already receiving health care. Under federal law, hospitals had to stabilize and treat people who arrived at their emergency rooms with acute conditions. And our state’s hospitals were offering even more assistance than the federal government required. That meant that someone was already paying for the cost of treating people who didn’t have health insurance. If we could get our hands on that money, and therefore redirect it to help the uninsured buy insurance instead and obtain treatment in the way that the vast majority of individuals did—before acute conditions developed—the cost of insuring everyone in the state might not be as expensive as I had feared.

That was then. Now Romney seems fine with notion of people waiting until they need to go to the emergency room to get care. Perhaps the sequel to No Apology should be titled “I’m Sorry for all the Stuff I did That Conservatives Don’t Like.”