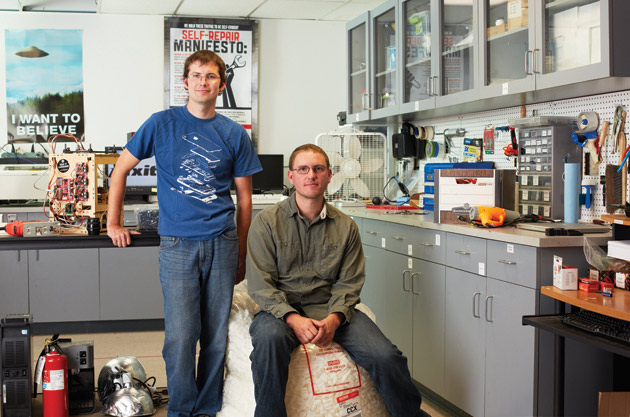

Luke Soules (left) and Kyle Wiens at iFixit's San Luis Obispo headquarters.Chris Leschinsky

In March, one day before the release of the iPad 3, iFixit cofounder Luke Soules traveled 17 hours from San Luis Obispo, California, to Melbourne, Australia, so that he could be the first person in the world—literally—to purchase one. Then, wielding a heat gun, some high-powered suction cups, eight guitar picks, a Phillips screwdriver, and a flat-headed tool called a spudger, he proceeded to gut the thing part by part, tweeting out photos as he did.

The stunt was catnip for a technology press eager for an angle on the latest launch and for gadget geeks hot to glimpse live nude photos of the iPad’s massive battery and dual-core A5X processor. But the teardown, one in a series, had a more subversive purpose. “We’ve figured out how to hijack the news cycle to change the dialogue to be more about long-term thinking and repair,” explains Kyle Wiens, who founded iFixit with Soules while both were students at California Polytechnic State University.

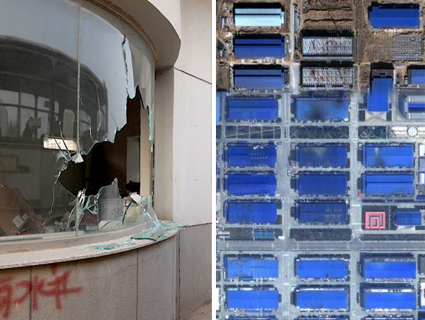

Indeed, most stories about the teardown noted why iFixit had rated the new iPad a paltry 2 out of 10 for repairability: glued-together components that make it nearly impossible to fix a cracked screen, replace a dead battery, or even disassemble a defunct iPad for recycling. “Apple has trained people to think that when their battery wears out it means that their device is wearing out and you just get a new one,” Wiens says.

iFixit—a fixture on Inc. magazine’s list of fastest-growing US firms—aims to change that assumption. It sells tools and parts and provides free, crowdsourced manuals showing how to repair everything from smartphones to bikes and coffeemakers. At last count, there were more than 6,000 photo-heavy how-tos on its website, two-thirds of them generated wiki-style by the company’s global community of around 50,000 fixers. (Millions more use the site but don’t contribute content.)

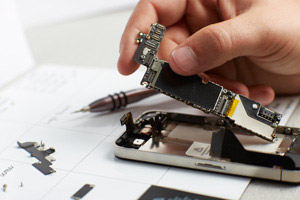

Watch iFixit’s Kyle Wiens pull apart the iPhone 5:

Fixing stuff, Wiens and Soules argue, is the ultimate act of rebellion against our consumerist culture. iFixit’s repair manifesto, available as a poster, holds several truths to be self-evident—some practical (“Repair saves you money”), some principled (“Repair saves the planet”), and some profound (“If you can’t fix it, you don’t own it”).

To understand why they believe that repairing gadgets can change the world, it’s instructive to take another look at that vivisected iPad 3. During my recent visit to the iFixit headquarters, Wiens shows me one with a demolished display, the glass a spiderweb of cracks, the rim fractured and chiseled. It’s one of several iPads the iFixit techs destroyed while searching for a simple way to take it apart.

In a cardboard box next to it are the pieces of another tablet, Google’s Nexus 7, which the techs had disassembled with a few twists of the screwdriver and a little coaxing with a spudger. They gave the device a 7 for repairability, noting that it was merely a millimeter thicker than the iPad 3 but infinitely easier to fix. Which might not matter when you first buy it, but it might after you drop it on the sidewalk. “If you have a cracked windshield, are you going to throw your car away?” Wiens asks rhetorically. “I’ve spent more on every computer I’ve ever bought than on any car I’ve ever bought. If I’m going to fix my car, why wouldn’t I fix my computer?”

Throwaway gadgets generate stupendous amounts of waste—we toss 20 to 50 million metric tons of electronics annually, the United Nations estimates—and recycling only reclaims a fraction of that. Also wasted is the energy used to create the products in the first place. (Apple attributes 61 percent of its products’ carbon footprint to mining and manufacturing.) “The only solution we’re going to have to fix our planet,” Wiens muses, “is to mine less and to make less.” (Click here to read about iFixit’s just-released chemical analysis of the top-selling smart phones.)

Wiens deconstructs a smartphone. Chris LeschinskyNot surprisingly, iFixit is revered in green-tech and hacker circles, and reviled among fanboys who argue that Apple should be left to design things as it sees fit. Its headquarters has an ecostartup aesthetic, complete with bike racks (any employee who wants one is given a bike), bottles of homebrewed beer, and photos of kids tending smoldering piles of e-waste. Its manuals, however, are largely written and refined not by the hipsters of Brooklyn or the gadget geeks of Silicon Valley but by rural people in places like Texas and Florida and the Midwest who may not find it quite so easy, or affordable, to head over to the nearest Apple store when something breaks.

Wiens deconstructs a smartphone. Chris LeschinskyNot surprisingly, iFixit is revered in green-tech and hacker circles, and reviled among fanboys who argue that Apple should be left to design things as it sees fit. Its headquarters has an ecostartup aesthetic, complete with bike racks (any employee who wants one is given a bike), bottles of homebrewed beer, and photos of kids tending smoldering piles of e-waste. Its manuals, however, are largely written and refined not by the hipsters of Brooklyn or the gadget geeks of Silicon Valley but by rural people in places like Texas and Florida and the Midwest who may not find it quite so easy, or affordable, to head over to the nearest Apple store when something breaks.

“This is not an ecosensitive thing they’re doing,” Wiens insists as we sit in his office looking at a map showing where iFixit’s far-flung authors are based. (He rarely makes a point without pulling out some data to back it up.) “They don’t identify themselves with some big repair, anti-manufacturer movement,” he says. “They’re just solving problems.”

Wiens is harder to pigeonhole. With his thick glasses and mild manners, he doesn’t seem too different from any young engineer who likes to take things apart. But talk to him for a few minutes and the polymath emerges. In the past year, he’s taken a film crew to Cairo and Nairobi to document informal repair economies, blogged for The Atlantic and the Harvard Business Review on subjects ranging from mineral mining to grammar, and testified before the International Trade Commission about electronics recycling.

Wiens is harder to pigeonhole. With his thick glasses and mild manners, he doesn’t seem too different from any young engineer who likes to take things apart. But talk to him for a few minutes and the polymath emerges. In the past year, he’s taken a film crew to Cairo and Nairobi to document informal repair economies, blogged for The Atlantic and the Harvard Business Review on subjects ranging from mineral mining to grammar, and testified before the International Trade Commission about electronics recycling.

A conversation with him feels a bit like a one-on-one TED talk, complete with visuals. In the course of one discussion he shows me the history of Apple’s self-reporting on its carbon footprint (“The problem is not lack of recycling, or e-waste—it’s mining and manufacturing”), a Chinese repair manual that cribbed photos from iFixit.com (“Please, take our manual and use it to fix things!”), a blog post including schematic circuit diagrams for the iPhone (“No repair shops in America have this, but all the repair shops in China have it”), and research by a British sociologist on Ugandan cellphone repair networks (“Far more informal recycling is happening than anyone has any idea of!”). iFixit may basically be an electronics parts shop, but it’s a parts shop with big ideas. “This is kind of a life ambition,” Wiens says. “To change the way we consume things.”

iFixit got its start in 2003 after Wiens and Soules tried to repair some old laptops in their Cal Poly dorm room and couldn’t find any parts or instructions. So they cannibalized a broken computer they found on eBay—many of their parts are still obtained chop-shop style—and began writing their own how-tos, testing them on art students for user-friendliness. Eventually, they started posting the instructions online and selling the needed parts and tools—including some (like the spudger) of their own design. By the time they graduated, in 2005, their business was generating $1 million in sales.

At the time, they were just hoping to cover their tuition. Wiens envisioned himself moving on to important projects that would improve people’s lives and hopefully make the world a better place. But as the grateful emails poured in, it occurred to him that iFixit already fit that bill perfectly. The environment, in his view, can only handle so much abuse for the sake of our high-tech conveniences. “I think all 7 billion people on Earth should have a cellphone,” he explains. “But if we all have a cellphone, we have to replace them much less frequently.”

Wiens concedes that changing people’s habits is an uphill battle. “We’re fighting some innate psychological tendencies where we get an endorphin boost from buying things,” he says. But his hope is that teaching us how to fix things might deliver its own endorphin boost. It’s not that far-fetched. Back home the day after my iFixit field trip, I sat down with my 13-year-old, a set of the company’s tiny screwdrivers, and a dead iPod Touch he’d scavenged from a friend. It turned out we didn’t even need tools. Within a few minutes, we’d revived the thing and my son was proudly loading it up with music. “That’s where the viral spread has come from,” Wiens had explained to me earlier. “We teach our customers to do amazing things. Once you’ve figured out how to repair your computer, you’re going to tell all your friends that they can do it too.”