Courtesy <a href="http://vague-terrain.com/">vague-terrain.com</a>.

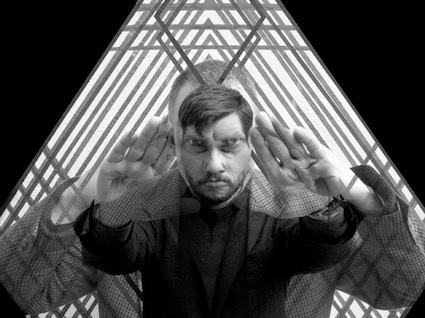

The subject is placed with his back on a mattress. He wears headphones that funnel gentle waves of white noise into his brain and halved ping-pong balls that cup his eye sockets. In another room, Drew Daniel, one half of experimental duo Matmos, is trying to transmit the concept of his forthcoming album to the subject using only his mind. After the subject has adjusted to his sensory deprivation, he will attempt to say what that concept is.

“It’s my stepmother singing ‘Wabash Cannonball,'” the subject tells MC Schmidt, Daniel’s musical and romantic partner, who is there in the room to record the responses. “It’s ‘Wabash Cannonball.’ That’s all I hear.”

For the past four years, Daniel has been conducting this ritual with friends and strangers using Ganzfeld, a method of ESP experimentation first conceived in the 1930s. Schmidt estimates that they’ve done at least 50 of these sessions across a variety of university campuses, and even at the home the couple shares. Their subjects’ verbal responses coupled with the vocal talents of friends (including Dan Deacon and the Dirty Projectors‘ Angel Deradoorian) are largely what you hear on Matmos’ latest, The Ganzfeld EP. It’s a teaser for a full-length release planned for next year, which will not only incorporate more experiments, but also celebrate Daniel’s and Schmidt’s 20th anniversary. They aim to call it The Marriage of True Minds.

Certainly there are easier ways to make a record, but Matmos isn’t interested in convenience. The pair met two decades ago at a Baltimore gay bar where Schmidt stuck a dollar into Daniel’s jockstrap (decorated with a plastic goldfish). Since then, they’ve gone on to produce some of the most uncomfortable and catchy performance art ever attempted. Their debut album sampled the neural tissue of crayfish. In 2006, Matmos dedicated the sounds of a fresh, inflated cow uterus to Valerie Solanas, the feminist writer who tried to assassinate Andy Warhol. The duo has collaborated with Bjork, held professorships at art institutes and at John Hopkins University, and most recently taught master classes on material poetics.

But even for a band that has sampled the squelchy sounds of a chin implant (see their 2001 album A Chance to Cut is a Chance to Cure), The Ganzfeld EP is out of Matmos’ usual wheelhouse. This time, instead of mining every day sounds of the physical world, Schmidt and Daniel mined a sampling of the collective unconscious. The responses served as rich sonic fodder for the EP, in which Matmos layered their subjects swelling chatter in harmony, and yes, beats.

So, did this telepathic messaging business actually work? That’s beside the point, according to Matmos. Daniel explains that instead of trying to prove or disprove ESP theory, Matmos hijacked the experiments “on behalf of music.” Still, the two noted some strikingly common threads in their subjects’ responses. One involved the image of a triangle, which made its way onto the EP as the song “Very Large Green Triangles.”

“I think that it was compelling to see people trust us enough to relax and let a lot of their guard down,” Daniel says. “In the process I felt that it would approach a therapeutic or psychoanalytic place where people are free-associating and generating inadvertent self-portraits.”

Ganzfeld originated as a term coined by German psychologist Wolfgang Metzger, who used this method of sensory deprivation to research Gestalt theory. In the ’70s and ’80s, Ganzfeld experimentation was revived by researchers looking for evidence of psi, or ESP. While many of those claims were eventually debunked, plenty of respected scholars bought into them over the course of the 20th century—Upton Sinclair, for example, the muckraking writer who exposed horrific conditions in the meatpacking industry, conducted his own series of ESP experiments with his wife, and published his findings in 1930. After a preface written by Albert Einstein, Sinclair went on to explain how his experiments led him to this conclusion. “Telepathy is real,” Sinclair wrote. “It does happen.”

Daniel, meanwhile, doesn’t want to make any hard and fast statements about paranormal phenomena. He even admits that he didn’t score highly on psychic-ability tests he undertook before conducting his musical experiment. “So make of that what you will,” he says. “There may be some people who are pitchers and some people who are catchers.”

Psychic ability notwithstanding, Daniel and Schmidt say the goal of their music is to engage people—to make high-concept stuff accessible and fun. “I kind of want to resuscitate modern art for regular people,” Schmidt says. The next album, he says, just deadpan enough to make matters ambiguous, “is going to be all about washing machines.”

Click here for more music coverage from Mother Jones.