It’s official. Or sort of. Mitt Romney appears to be finishing the presidential race with 47 percent of the popular vote. According to the National Popular Vote Tracker, Romney’s take of the nationwide vote, which is still being tallied in several states, now stands at 47.43 percent. Rounding down, that’s the magic number. And given that the states that have not finalized their vote count include California and New York, where Obama won big, it’s likely Romney’s percentage will tick down a bit. With Obama bagging 50.86 percent, the history books will record the contest as a 51-47 percent contest.

Romney was stuck at 47 percent even within twelve swing states, where he drew 47.32 percent of the cumulative vote. In the non-swing states, he pocketed 47.49 percent. This is highly convenient. Anytime the results of this presidential race are referenced, there will be a reminder of Romney’s now infamous 47 percent rant.

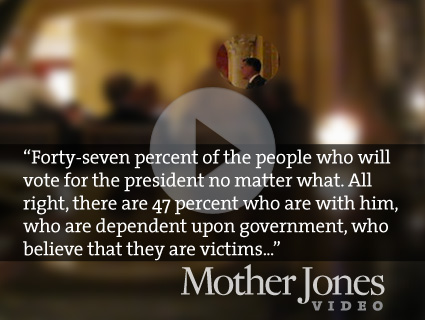

In the aftermath of the election, numerous politicos—and strangers on the street—have told me they consider the revelation of the 47 percent video to have been the game-changer. Various post-mortems have cited Romney aides saying the same. There is, of course, no way to know what might have transpired had the video not roiled Romney’s campaign for nearly two weeks during the crucial general-election period, where every single day counts. The video certainly reinforced the narrative that Romney’s critics—including the Obama campaign—had been pushing: He was a 1-percenter who could not relate to middle- and working-class Americans confronting serious economic challenges and troubles. But the 47 percent story also caused Romney another problem; it stole time.

Money is not necessarily the most precious resource for a political campaign; it is time. Money can always be raised. Time cannot. After the political conventions, Romney had nine weeks to execute his strategy for winning the presidency. As campaigns do, his crew mapped out how it would use those weeks: when it would run ads, when it would stress particular messages, when it would focus on this or that state. The dust-up created by the 47 percent video lasted nearly a fortnight, throwing sand into Romney’s gears during that crucial period. A week and a half after Mother Jones broke the story, a top executive at a broadcast news outlet sent me an email: “Used your video tonight (not too many stories are still going 10 days strong).” The 47 percent video had become one of the longest-running dramas of the 2012 campaign.

During those days, Romney was knocked off his already not-too-sure footing—which he wouldn’t regain until the first debate, thanks to President Obama’s limp performance. By then, the Obama campaign and its allies were using the 47 percent video in a series of ads that reinforced its initial impact on the race. On election night, an Obama adviser told me that the campaign did not rush out 47 percent ads right after the video emerged because in focus groups, undecided voters were bringing up Romney’s remarks without prompting. His 47 percent comments had penetrated the voting public so fast and so far that the campaign had no cause at first to spend money to remind voters.

Romney was the 47 percent man. And that’s how he is ending up.

In a private post-election call with funders that was revealed by the New York Times, Romney explained his loss by saying that Obama had showered key parts of his coalition with “gifts,” by which he meant federal support for college loans, a health care law that allows children to remain on their parents’ policies, and an executive order that permits the children of undocumented residents to remain in the United States. With those comments—something of a sequel to his 47 percent tirade—Romney was failing to take personal responsibility, holding the government accountable for what happened to him, and portraying himself a victim. Now where have we heard that before?