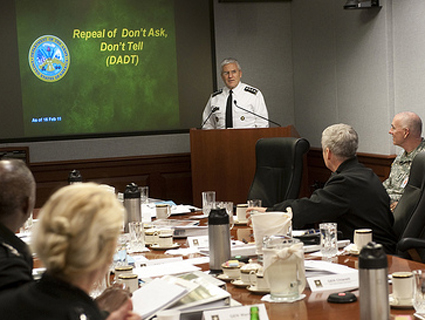

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta and Gen. Martin DempseyDOD photo

If the United States had previously allowed women to serve officially in military combat roles, including special operations forces, there might be fewer sexual assaults in the armed services, the Pentagon’s top general told reporters Thursday.

Having studied the issue of rampant sexual misconduct in the ranks, Gen. Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, noted that he has concluded that the phenomenon exists partly because women have been subordinated to men in military culture: “It’s because we’ve had separate classes of military personnel.”

Dempsey’s comments came during a press conference with Defense Secretary Leon Panetta, with the pair announcing the end of restrictions on women serving in previously all-male combat-arms roles, such as within the infantry, the artillery, and special forces. “We’ve been on a long journey, a long journey towards achieving equality, and there have been some tough challenges along the road,” Panetta said.

Despite the announcement, the road to full equality may well be rocky; each of the armed services has until May to report to the incoming defense secretary (presumably Chuck Hagel) on how—and how quickly—it will integrate women into combat billets. “We want to make sure we get the standards right, and we don’t overengineer them either,” Dempsey said.

Nevertheless, the move largely codifies a practice long under way in combat zones like Afghanistan and Iraq, where women serving in what are technically non-combat roles—such as patrolling in vehicles and aircraft—can find themselves under fire. And the transition to women serving fully side-by-side with men has been happening in several services already. “Women are now in submarines, and that was one of the concerns at the time,” Panetta said, answering a reporter’s questions about “privacy issues” among troops. “Women are fighter pilots now. So Air Force, Navy have moved in that direction. The Marines and the Army are now gonna move in that direction.”

Dempsey echoed that. “We figured out privacy right from the start,” he said, referring to Desert Shield operations in 1990 and 1991 that required men and women to huddle together in ad hoc desert encampments.

Asked whether the military’s elite Seals and Green Berets might soon see female recruits, Dempsey said he had discussed that with Army Chief of Staff Ray Odierno and Marine Commandant James Amos, both combat veterans themselves. “I think we all believe that there will be women who can meet those standards,” he added.

Dempsey appeared to chafe when asked by a reporter about his personal opinions on whether women would affect combat readiness: “I graduated from West Point in 1974. It was an all-male institution. I went back to teach at West Point in 1984 and found the place far better than it was when I had been a cadet… I attributed a good amount of that to the fact that we opened up the academy to women.”

Dempsey noted that allowing women to serve in such coveted roles as infantry could help erode a male-dominated culture in which sexual assaults have been rising among uniformed personnel. “The more we can treat people equally, the more likely they are to treat each other equally,” he said.

Both men conceded that they didn’t know if this move means that women will have to register for the draft with Selective Service, as young men are required to do. “That’s not our operation,” Panetta said, stumbling over his words, then adding, “I don’t know who the hell controls Selective Service, to tell the truth.”