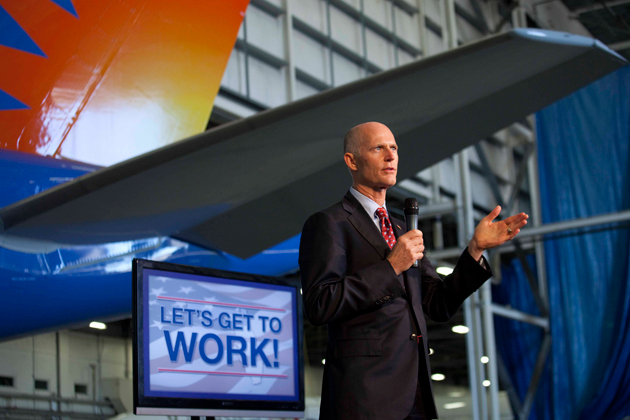

Florida Governor Rick Scott on the campaign trail.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/scottforflorida/5243034270/sizes/m/in/photostream/">Gov. Rick Scott</a>/ Flickr

Florida Gov. Rick Scott was elected in 2010 almost entirely thanks to his activism opposing the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. Scott spent $20 million of his own considerable fortune attacking the law, and the Republican backed the state’s lawsuit challenging its constitutionality all the way to the Supreme Court. Scott had declared last summer that Florida would implement the law basically over his dead body, including the optional part that would provide federal funding to expand Medicaid to people making up to 138 percent of the poverty line.

So it was a bit of a surprise Wednesday when he announced suddenly that he had changed his mind: Florida should embrace the Medicaid expansion. We’d like to think that this article might have had something to do with his decision; Scott himself claims that mother’s death inspired his change of heart. But it’s more likely that the decision was a direct result of the US Department of Health and Human Services agreeing to grant Florida a waiver that would allow it to move more Medicaid recipients into private managed-care plans—many of which are part of huge corporate insurance companies waiting to cash in on the latest installment of Obamacare. (The Medicaid expansion is expected to send $66 billion in federal funds to Florida in the next decade.)

Scott has been saying for months that if HHS approved Florida’s waiver request, he might be more willing to take the Medicaid expansion. He was in DC in January meeting with HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius over the issue. But HHS’s decision to grant the waiver was somewhat surprising, given that the state was asking to expand a very troubled pilot project going back to the Bush era. The pilot project, which also required a waiver from HHS, allowed the state to put Medicaid recipients in five counties into private, HMO-type health plans rather than the traditional government health plan for the poor and disabled. Scott has championed the pilot as an innovative way of keeping government spending in check. Health care advocates, though, saw the program as a major disaster.

A study by the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute backed up their claims, finding that the biggest problem with the “reform” was that insurance companies got into the program thinking they’d make a lot of money, only to discover that they actually had to care for people who were expensively sick. Nine plans dropped out of the pilot project in a year, leaving many patients without access to any primary health care. There were horror stories, too: the woman denied a kidney transplant, the man with a lifelong seizure disorder who suddenly found he couldn’t get the Botox injections that calmed his seizures. If the patients weren’t getting dropped by the managed-care plans, they were fleeing them for whatever other options they could find. There’s no evidence that the private plans saved the state any money.

“We’ve been raising hell for a couple of years saying this is a problem,” says Laura Goodhue, executive director of Florida CHAIN, a consumer advocacy group that works for the uninsured in Florida. “When you’re caring for an expensive population with multiple conditions, lots of mental-health issues, the only way to make a profit is to delay and deny services, and that’s what we saw in Florida.”

Some of the companies chosen to lead the Medicaid “reform” pilot project weren’t exactly stellar performers before they got there. Wellcare, one of the HMOs in the project (and a major donor to Florida’s GOP), paid out $80 million in 2009 to settle charges federal criminal charges that it had lied about how much it actually spent on health care for poor kids and other vulnerable clients. Last year it paid out another $137.5 million to settle False Claim Act lawsuits alleging schemes to wring extra money out of Medicaid programs, including those in Florida, as well as cherry-picking customers and other abuses.

Despite experiences like these, the Florida Legislature in 2011 voted to expand the pilot project, and big insurers have been jumping to get into this market, (The insurance giant WellPoint, for instance, recently bought Amerigroup, a large Medicaid managed care company, to get in on new business thanks to Obamacare.) But to fully implement its new privatization law, Florida needed the federal government, which pays for about half the program, to waive certain requirements designed to protect patients.

Consumer advocates had fought the law and have been lobbying the Obama administration against granting Florida a waiver. And they had some success. Recently, HHS refused to allow Florida to let HMOs charge Medicaid enrollees $10 co-pays for doctor visits or $100 for emergency room visits for non-emergency care, as the state law allows.

And while Scott has heralded this week’s news about the latest waiver approval as a victory, what HHS actually agreed to is less than the governor and the HMO companies lobbying for the changes were probably hoping for. Among other things, HHS said that the state still has a long way to go to protect consumers enrolled in private plans, and that the approval of the waiver was “conditional,” premised on Florida developing “robust” community input and data-driven goals and strategies.

Goodhue says the new waiver has many more consumer protections built into it than the one granted under the Bush administration, and that hopefully it will prevent some of the problems that occurred under the state’s pilot program. She still doesn’t think that managed care is the way to go to improve Medicaid. But in the end, she’s pleased that it’s not as bad as it could be, and if it means that a million Floridians will get new coverage, that’s something advocates can get behind.