Mike’s morning commute to the battlefield begins with his usual Egg McMuffin and black coffee from a McDonald’s drive-through window in Alamogordo, New Mexico. After driving out of town in his Ford pickup, clearing a security checkpoint, and attending a daily briefing, he will be remote-controlling an MQ-9 Reaper drone 10,000 feet above Afghanistan.

But don’t call Mike—an Air Force major based at Holloman Air Force Base—a drone pilot. (And don’t call him Mike; I’ve changed his name and that of his colleagues by request.) The preferred nomenclature inside the military for unmanned planes is RPA, for Remotely Piloted Aircraft. “Drone” conjures images of brainless bots on autopilot, an implication not appreciated by the three-person crew (pilot, sensor operator, intelligence analyst) typically tasked with operating the military’s high-tech workhorses.

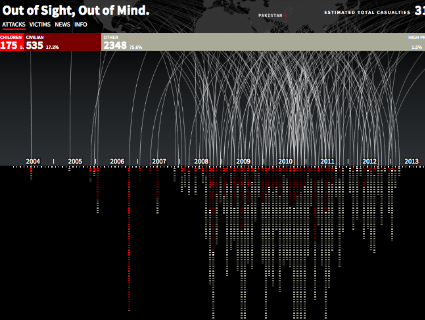

The word drone also evokes monotony, which is what fills much of the pilots’ daily routines. Though strikes on suspected terrorists and the resulting civilian casualties get the headlines, the lion’s share of remote piloting consists of quieter, more shadowy work: hour after hour of ISR—intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Sitting in ergonomic chairs in ground control stations—essentially souped-up shipping containers—RPA operators coordinate with ground intel to identify human targets, then track them with high-powered zoom lenses and sophisticated sensors. (A nine-camera sensor nicknamed Gorgon Stare is capable of streaming full video with enough resolution to discern facial expressions.)

“It might be little things like a group of kids throwing rocks at goats, or at each other, or an old man startled by a barking dog,” says Mike. “You get a sense of daily life. I’ve been on the same shift for a month and you learn the patterns. Like, I’ll know at 5 a.m. this guy is gonna go outside and take a shit. I’ve seen a lot of dudes take shits.”

“Another time we followed this guy outside his house for half an hour, and all he did was go scoop water from a stream. Seeing that just made it sink in—how we live worlds apart,” he recalls. Asked about feeling any sense of attachment to his targets after long hours of scrutiny, Mike replies, “Whether it gives me empathy or sympathy or just familiarity I’m not sure. We compartmentalize the job like anyone else.”

Yet the pilots insist their distance from their targets does little to desensitize them to the real-life consequences of their actions. Ryan, a captain who used to fly a B-52 bomber, says, “Oh yeah, you still get buck fever; you know you’re about to do some damage. The heart rate goes up. The main thing is repetition, so whether it’s a training weapon or 2,000-pound laser-guided missile, it doesn’t feel different.”

Surveillance often includes hovering indefinitely to scan for IEDs or ambushes. There is massive demand for this “overwatch” work, as American commanders on the ground now feel blind without it. Mike describes an incident when employees of a private security agency dressed in local garb were mistaken for Taliban fighters. An attack controller on the ground called in a Reaper strike, but when Mike examined the area, he noticed that the men were openly brandishing their weapons, suggesting they were friendlies. He decided to withhold ordnance and instead asked ground forces to investigate, whereupon they confirmed his assumption. He was awarded a Pilot Safety Award of Distinction, and months later had an unlikely run-in with the owner of the firm that employed the contractors. He says the CEO shook his hand and told him, “Thanks for not killing my guys.”

But an award or handshake can’t replace the buzz of flying at Mach speed over a combat zone. Many early recruits to the program flew jets, bombers, or cargo planes before being “asked” to transfer to drone duty under the impression they could reassign to a base of their choosing after putting in time on RPA rotations. But as demand for their new skill set increased, the timelines became moving targets. Some have been flying drones so long they would need expensive retraining to fly regular aircraft again.

“I’m overpaid, underworked, and bored,” says Ryan. “What the Air Force doesn’t get is that they can’t throw money at us to make us happy. I didn’t even know how much a pilot made when I enlisted. I just wanted to fly.” Brad, who flew a B1 bomber in Afghanistan and is now an RPA instructor at Holloman, compares it to “being transferred from marketing to the accounting department.” Ryan says pilots in their situation have taken to calling themselves the “lost generation,” and many have become resigned to the notion that if they stay in the Air Force they might never feel g-forces in a real cockpit again.

“It’s tough working night shifts watching your buddies do great things in the field while you’re turning circles in the sky doing ISR,” says Ryan. And the dusty town of Alamogordo doesn’t offer much in the way of extracurricular perks. “If we can do this job from anywhere, why can’t they just put the base in Hawaii?” wonders Mike, only half-joking.

This isn’t to say RPA pilots are a disgruntled lot; they see value in what they’re doing, but it’s an adjustment for the guys who followed their Top Gun daydreams only to find themselves landlocked in air-conditioned containers.

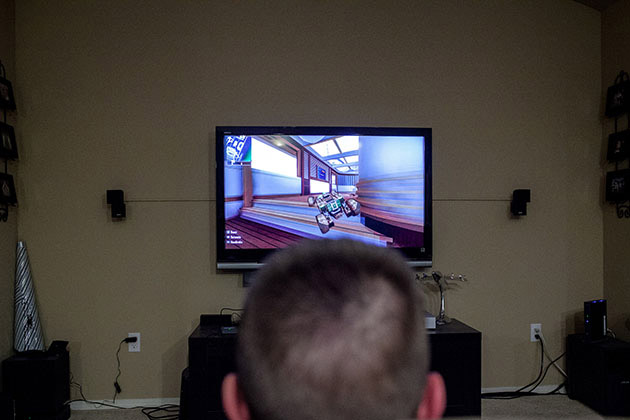

Still, these are boom times in the RPA business. Classrooms at Holloman are filled with recruits who will soon deploy to the virtual front lines at the base or similar facilities in Nevada and South Dakota. Some trainees have logged zero hours of actual manned flight time, though Ryan believes “the video game generation may have advantages in some respects.” And there are plenty of pilots happy to raise their families inside the suburban confines of an Air Force base without needing to deploy abroad. It’s hard to beat making a 7,500-mile commute in just a few minutes.