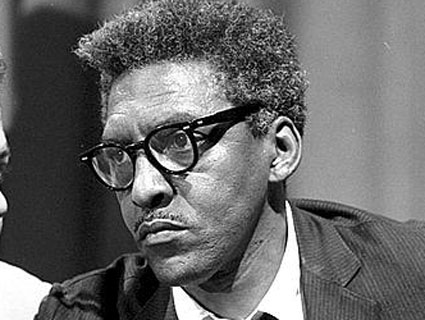

Bayard Rustin at a March on Washington news briefing in 1963.<a href="http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsc.01272/">Warren K. Leffler</a>/Library of Congress

Bayard Rustin was for years one of the least known and celebrated major players in the civil rights movement. Now Martin Luther King Jr.’s trusted adviser—the black, gay, “badass” pacifist who organized the March on Washington—is finally getting his due 50 years after the landmark demonstration.

Rustin, born in Pennsylvania in 1912 and raised by his grandfather and his Quaker grandmother—who, along with Mahatma Gandhi, influenced his philosophy of pacifism—had his hand in several major moments in a fight for equality that would span his entire life. He helped organize and participated in the first freedom ride, 1947’s “Journey of Reconciliation” (for which he and several other participants were jailed and put in a chain gang). In the 1950s, he advised, strategized, and raised money behind the scenes for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, helping to direct King’s rise to national prominence. He’s also credited with honing the King’s nonviolent strategy. Later, Rustin was the mastermind of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (now simply known as the March on Washington), organizing it in just two months. But Rustin was kept in the shadows by the homophobia of both his enemies (segregationist Strom Thurmond used Rustin’s sexuality to denigrate the movement) and his allies.

“We must look back with sadness at the barriers of bigotry built around his sexuality,” NAACP Chairman Emeritus Julian Bond, who knew and worked with Rustin, wrote in the forward for 2012’s I Must Resist, a book of Rustin’s letters. “We are the poorer for it.”

Although prejudice kept Rustin behind the scenes—and out of history books—his name is finally making headlines. In March, President Obama awarded Rustin, who died in 1987, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The National Black Justice Coalition, a black LGBT civil rights organization, launched a movement to celebrate Rustin on what would have been his 100th birthday in 2012 and created the Bayard Rustin 2013 Commemorative Project, which highlights his contributions to the March on Washington.

Michael G. Long, who edited I Must Resist, tells Mother Jones the accolades are long overdue. “Rustin is finally emerging out of the shadows,” he says. “This is a man who labored for decades behind the scenes. And he labored there willingly, but he was also pushed there and kept there and confined there by civil rights leaders.”

Rustin should be remembered not just for his fight for racial equality, which was accompanied by a quest for economic justice, but also his unflinching participation in the fight for gay rights. In a 1986 speech he advocated for a change in civil rights activism: “The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: gay people.”

Sharon Lettman-Hicks, executive director of the National Black Justice Coalition, told USA Today this month that her organization is “advocating the preservation of his legacy by removing the barriers that didn’t allow society to get to know all of Bayard Rustin. His legacy deserves its due.”

“I hope that Bayard can bask in the daylight for decades and centuries to come and that we’ll finally see his name in history books in high school and elementary school,” Long says. “I hope that every elementary school student will come to know that Bayard Rustin was the man who organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in eight short weeks.”