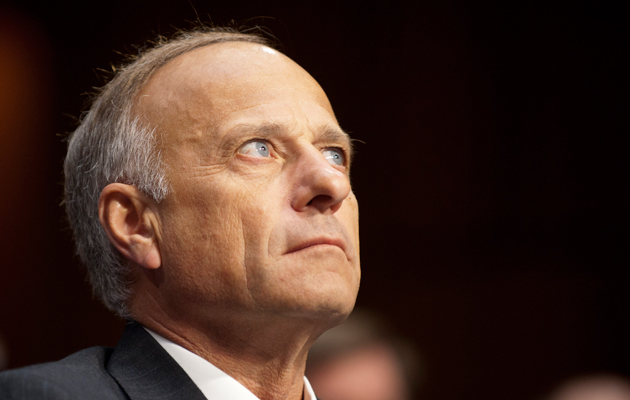

The Washington Times/ZumaPress.com

Comprehensive immigration reform has no greater enemy in Congress than Rep. Steve King (R-Iowa). In July, he warned the conservative site Newsmax that most undocumented immigrants “weigh 130 pounds and they’ve got calves the size of cantaloupes because they’re hauling 75 pounds of marijuana across the desert.” In June, when a coalition of undocumented immigrants stopped by his Capitol Hill office, he tweeted that he had been “invaded.” He once constructed a replica border fence from scratch on the floor of the House, just to show his colleagues how it’s done.

King is Washington’s most anti-immigrant congressman, but the patch of northwest Iowa he represents is surprisingly devoid of his brand of nativism. Statistically, he’s an outlier. Voters in King’s district support a path to citizenship for undocumented residents by a 2 to 1 margin, according to a survey last month by the Tarrance Group, a Republican polling firm. In recent months he has run into opposition at home from a bipartisan coalition of immigrants, faith leaders, business interests, and even law enforcement officers, who view comprehensive immigration reform as imperative to the health of the increasingly diverse region. On Thursday, King finally met with supporters of immigration reform at his Sioux City office—on the condition that he be allowed to videotape it.

Their message for King is a simple one: They’d like him to tone it down.

“I think the biggest thing that the immigrant community gets a black eye for ends up being drug-smuggling and this type of thing,” says Gary Malenke, president of Natural Food Holdings, a meat processing plant in King’s district, responding to the congressman’s cantaloupe comment. “I’m sure to some degree it happens, but not every immigrant worker that’s coming here is a drug smuggler, okay? I think if we worried more about all the white Caucasian people in the United States that were using the drugs we’d probably solve the issue.”

Sioux County Sheriff Dan Altena, a Republican who has been re-elected to his post twice by overwhelming numbers, says he supports comprehensive immigration reform that includes a path to citizenship for people here illegally. In the 2008 and 2012 elections, the rural county on the South Dakota border gave 83.6 percent of its vote to Mitt Romney, making it far and away the most Republican county in the state. But when it comes to immigration, Altena—who was re-elected with 96 percent of the vote last fall—believes King is speaking for just a fraction of the district.

“I think a lot of the people just don’t even think very much about it,” Altena says. “There have been very few people that are outspoken adamantly against the immigrants that are here. I don’t recall anything really being written in our local papers or people making public statements that we have got to do something about it—I haven’t seen anything about that.”

Part of that stems from a simple demographic truth: Iowans need immigrants as much as immigrants need Iowa. Over the last two decades, even as residents have reliably cast their votes for King every two years, they have also become increasingly dependent on an influx immigrants to counterbalance an aging white population. The Hispanic population of Sioux Center* grew from 4.7 percent in 2000 to 13.1 percent in 2010. Today, one in five babies born in the county is Hispanic. And that number is still increasing. (A proper head count of undocumented residents in the county is impossible to pin down, but one pro-reform activist placed it as high as 80 percent of the local Hispanic population.)

“It’s a difficult issue because Congressman King is a Republican and my county here is strongly Republican and certainly that’s [a voting bloc] I need to be re-elected,” he says. “You wonder, is this damaging?” But, he adds, “I’ve been in law enforcement in the area for 34 years, so I’m pretty well informed about the area and where people are at—I just don’t see the immigrants as being a problem here for people.”

Of course, even if King’s constituents broadly disagree with him on immigration, there’s no reason to expect it will impact him at the polls. (Despite facing a well-financed challenger in Democrat Christie Vilsack, he ran virtually even with Mitt Romney in the district in 2012.) King is a very conservative Republican in a very conservative Republican district—and the undocumented immigrants stigmatized by King have no recourse at the ballot box. On the issues that tend to motivate the voters of northwest Iowa, things like abortion and agriculture policy, King’s in their court.

The real immigration problem facing the county, according to Altena, is one of enforcement. The sheriff’s resources are constantly drained by having to enforce unwieldy laws, which when properly followed can work to the detriment of the community. For example, if a deputy cites an undocumented resident for a traffic violation, he is then obligated to notify the federal authorities and take the offender to the county jail, beginning a time-consuming bureaucratic slog.

“Well, what happens is a person is booked into our jail, and the ICE officials, sometimes they’ll deport them, sometimes they don’t,” he says. “Oftentimes, when they deport them it ends up being somebody who has a family here and is working and then that family is put into the hands of our state department of human services, because now all of a sudden they don’t have a place to go and their kids don’t have a place to go and it becomes a real mess.”

Instead, he favors the reform package that passed the Senate in July (slammed by King as “amnesty”) which included a pathway to citizenship for people who are living here illegally, provided they pay a penalty. “As a law enforcement officer, I’m all about the rule of law—that’s our job,” he says. But, he adds, “When you’re talking rule of law, I think the present immigration reform still deals with the people that violated the laws. It’s not total amnesty, in my opinion.”

For the undocumented immigrants of Sioux County, the support of community leaders like Altena is welcome—but it doesn’t mean they’re in the clear. That’s something Eduardo Rodriguez knows firsthand. Rodriguez came to the United States illegally from Mexico with his family when he was a year old, and he’s lived in Orange City, a town of about 7,000, since he was four years old. His parents work at a dairy.

At school he heard the occasional ethnic slur, and he acknowledges that fears of racial profiling complicated the already difficult process of integrating into a community separated by a language barrier and a century of history. The community’s undocumented residents live in constant fear of a misstep that might lead to deportation. But Rodriguez is also adamant that King is the exception, even in his own backyard. “No one’s ever really face-to-face come up to me and said something prejudiced,” Rodriguez says. “I definitely think this area it’s a lot more complicated than what a lot of people across the country think.”

Just take it from Altena.

“I see a lot of immigrants here that are good folks and are here because they’re running from violence in their country, they’re running from poverty in their country, and they’re coming here to work,” Altena says. “And granted they did it the wrong way, but I’m familiar with immigration, having gone through international adoption four times. It’s hard! And these folks, for many of them there wasn’t any other way.”

*Correction: This article originally identified Sioux Center as the county seat. The county seat is Orange City.