People write about China’s growth so much it’s daunting to wring out something new. But—wow—when you see it for the first time in a few years, it still delivers one hell of a punch.

I lived in China for a year before Beijing’s 2008 Olympics (a kind of development event horizon in China’s history, towards which the whole country hurtled), and I’ve been back regularly enough to marvel at changes first hand.

But I have never before been as dumbfounded as during a train ride this week from Beijing through a swathe of China’s northeast coal belt. My colleague Jaeah Lee and I were whisked away from the capital on rails that carry sleek new bullet trains (in just two years, China will have completed 18,000 kilometers (11,200 miles) of high-speed railway lines, leaving the US limping). We zoom at 300 kilometers (186 miles) per hour through unabated upheaval.

The scene could be a panel from a graphic novel. For hours, not a single bird stirred around the hundreds of empty skyscrapers that hang lifeless over farms; they will house the newly urbanized from China’s rural areas. Every bit of the shadowy landscape in China’s northeast has been pressed into the service of an all-pervasive industry: power generation. China continues to be the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, according to the World Resources Institute. It’s clear to me now: Where one coal power plant stops, another begins. A thick brown air blows and for a moment the trees look like nature’s very own protestors, shaking their fists at the sky (the human variety are strictly banned—though public outrage finally forced the government to publish air quality data in 2012).

“I feel weak and powerless,” a young filmmaker surnamed Yang told me later in a Xi’an cafe when I asked him about climate change and pollution. “I’ve seen so many pioneering and brave people dare to stand up, only to be punished.”

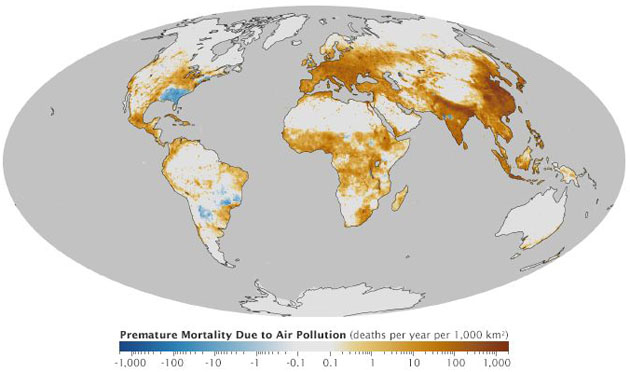

This year’s tipping-point event for the public debate, dubbed by expats as “airpocalypse,” covered 2.7 million square kilometers of the country with a pall of smog and impacted more than 600 million people. We pass through Zhengzhou, ranked among the four worst cities in China for air pollution; the city consistently registers levels well over China’s official scale for what’s called PM2.5—dangerous tiny particles from coal-burning and industry. In the first half of this year, China’s levels of these particles were three-times worse than levels advised by the World Health Organization. It’s this kind of air pollution that contributed to 1.2 million premature deaths in China in 2010, researchers say. My Beijing friends will call me a wimp, but I’ve developed a persistent cough these last few days. It’s hard to breathe.

“I think the air quality is awful all around the country,” a Chinese man surnamed Liang tells me (like the filmmaker, he didn’t want to give his full name). “For average citizens, there are not many things we can do about it…We are not yet a democracy. Average people can only try to live their own lives.”

According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report released Friday, greenhouse gas levels are now higher than at any point in “at least the last 800,000” years. With a quarter of global carbon dioxide emissions now coming from China, the world’s most populous country will have an outsized influence on the future of climate change. That didn’t go unnoticed at the IPCC release in Stockholm, Friday. “If China can mind its business well, it will be a great contribution to the world,” said report co-chair Dahe Qin, speaking in Chinese in response to a question from a Chinese reporter, according to a translator.

There are some encouraging signs of change. The new government under Xi Jinping is finally taking seriously the threat of coal to China’s air: It’s simply untenable for any government, let alone one that depends so fundamentally on suppressing unrest, to ignore. This month, Beijing committed to progressively shut down its coal plants inside the city within four years, according to official plans that also reduce burning in China’s coal-producing provinces. Presidents Obama and Xi Jinping have agreed to curb the use of hydrofluorocarbons, which are used in refrigerants, in a move that could lead to a strengthening of the Montreal Protocol as an international climate agreement. And China has sunk millions into solar development, as you can see in the graph below, outpacing the US dollar-for-dollar in renewable energy investment, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. China’s National Development and Reform Commission—which looks after big-picture planning—announced earlier this year that renewable energy investments in the country could total $294 billion in the five years ending in 2015. This includes the incredible growth of 22 percent from 2011 to 2012. A closer look at the data shows the US has a lot of catching up to do if it wants to compete with the world’s biggest clean energy player.

But it’s hard to have confidence staring out the window of this railroad car. The difference between inside our modern train and the turbulent outside world couldn’t be greater. Inside is quiet, air-conditioned and pleasurably fast. Outside, the environmental crisis continues to unfold before our eyes. It’s a sense of powerlessness shared by Chinese people we speak to.

“Under an ironfisted and strong government, what we normal people can do to change the country is very limited,” said Yang, the filmmaker. “That’s why I feel sad and disappointed.”