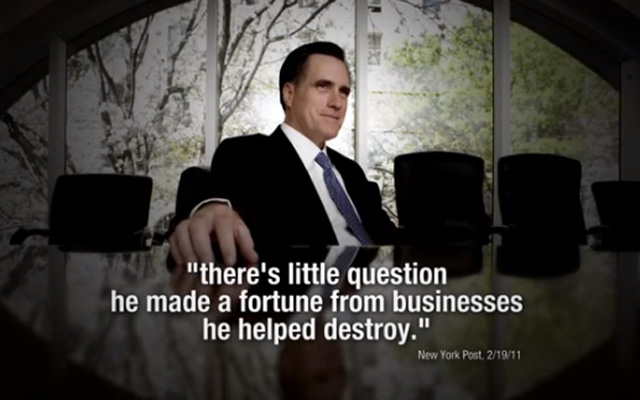

A screenshot of the Priorities USA Action 2012 ad "Stage" attacking Mitt Romney.<a href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oLo0Jwj03JU">Priorities USA Action</a>/YouTube

A recent headline over at the Atlantic captured the mood when it comes to the state of money in American politics: “There’s No Way to Follow the Money.” The author, former Reuters editor Lee Aitken, was referring to the web of “social welfare” nonprofit groups moving hundreds of millions of dollars in dark money all around the country with the goal, ultimately, of influencing elections and shaping policy. Aitken has a point: As deep as reporters dig, it’s harder than ever to track where the money’s going, how it’s being spent, and who’s taking a cut along the way.

Following the dark money isn’t any easier when timid or dysfunctional watchdogs plainly fail to do their jobs. Fingers point most often to the Federal Election Commission, which is at the moment an underfunded, ideologically divided, broken institution. But a new Sunlight Foundation analysis identifies another culprit: the Federal Communications Commission, the nation’s top cop when it comes to TV, radio, and broadband.

Here’s the back story: Tucked inside the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, a landmark piece of legislation better known as “McCain-Feingold” after its two sponsors, was a new requirement that local TV stations make available to the public information about political ad buys, including how much was spent and what candidates or issues were mentioned in the ad. Post-Citizens United, spending on political ads has exploded—$5.6 billion was spent in 2012, a 30 percent increase from 2008. Broadcasters’ ad data can provide journalists, campaign staffers, activists, and anyone else with detailed and useful information on the ads running all over the country.

The problem? TV stations are ignoring the law, leaving the public in the dark.

A Sunlight Foundation analysis of 200 randomly-chosen ad buys by PACs, super-PACs, or nonprofits found that fewer than one in six actually disclosed the name of the candidate or specific election referenced in the ad. The most important fields on the ad buy paperwork are blank, and the TV stations that are so eager to rake in all those revenues aren’t prodding the ad buyers to fully disclose what they’re doing.

The FCC could crack down on this if it wanted. Sunlight’s Jacob Fenton explains why the agency isn’t acting:

TV stations could be penalized for leaving out disclosure information, but the FCC has shown little appetite for doing so. Although occasional enforcement checks took place in the years after the reforms were adopted, more recently the FCC has fallen back on a “complaint driven” process. In other words, the agency won’t act unless someone asks it to. But because the vast majority of the political ad filings are hidden away in file cabinets at broadcast stations, available only during business hours when most voters are working, few people ever see them, let alone complain.

Steve Waldman, an Internet entrepreneur and journalist who worked as a senior advisor to former FCC chairman Julius Genachowski, said the nation’s communications watchdog was leery of getting stuck with the unenviable position of campaign cop. “When it comes to political stuff, there’s extra sensitivity at the commission because it’s the one area where Congress jumps up and down and says, ‘If you do that we’re going to come and slap you in the head,'” Waldman said.

Tom Wheeler, who just replaced Genachowski, saw his Senate confirmation vote held up by Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, over the issue of political ad disclosure. In a statement, Cruz said he lifted the hold after Wheeler said he’d make political ad funding disclosure “not a priority.”

It’s not all bad news on the political ad transparency front. In August, a judge ruled that the FCC could proceed with a plan to require several hundred broadcast stations located in the nation’s 50 largest cities to post their ad files online. Sunlight, among others, is working to make those files accessible and easily searchable to anyone with an Internet connection.

In the campaign finance world, that’s progress. But it’s enough. The FCC and the TV stations themselves need to feel more pressure to ensure that those ad files comply with the law. It’s one of the few useful tools we have nowadays for following that shadowy money trail.