Imago/ZUMA

In November 2010, Russia’s Sanctity of Motherhood organization kicked off its first-ever national conference. The theme, according to its organizers, was urgent: solving “the crisis of traditional family values” in a modernizing Russia. The day opened with a sextet leading 1,000 swaying attendees in a prayer. Some made the sign of the cross, others bowed or raised their arms to the sky before settling into the plush red and gold seats of the conference hall at Moscow’s Christ the Savior Cathedral.

On the second morning of the conference, the only American in attendance, a tall, collected man, stepped up for his speech. Larry Jacobs, vice president of the Rockford, Illinois-based World Congress of Families (WCF), an umbrella organization for the US religious right’s heavy hitters, told the audience that American evangelicals had a 40-year track record of “defending life and family” and they hoped to be “true allies” in Russia’s traditional values crusade.

The gathering marked the beginning of the family values fervor that has swept Russia in recent years. Warning that low birth rates are a threat to the long-term survival of the Russian people, politicians have been pushing to restrict abortion and encourage bigger families. Among the movement’s successes is a law that passed last summer and garnered global outrage in the run-up to the Sochi Winter Olympics, banning “propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations to minors,” a vague term that has been seen as effectively criminalizing any public expression of same-sex relationships.

Anti-gay groups have made tormenting the LGBT community a national and organized affair: Vigilante gangs have used social media to lure hundreds of gay people to fake dates and then disseminate videos of them being beaten or sexually humiliated, garnering hundreds of thousands of followers. Arrests and beatings at gay rights demonstrations are commonplace. This month, LGBT activists were arrested in Moscow and St. Petersburg hours before the Olympic opening ceremony and have been detained in Sochi itself.

Since Jacobs first traveled to Russia for the Sanctity of Motherhood conference, he and his WCF colleagues have returned regularly to bolster Russia’s nascent anti-gay movement—and to work with powerful Russian connections that they’ve acquired along the way. In 2014, the World Congress of Families will draw an international group of conservative activists together in Moscow, a celebratory convening that Jacobs foreshadowed on that first visit, when he ended his speech triumphantly: “Together, we can win!”

How the World Congress took Russia

The Sanctity of Motherhood conference represented a homecoming of sorts for WCF, which was conceived in Russia in 1995. Since the Soviet Union’s collapse, two sociology professors at Lomonosov Moscow State University, Anatoly Antonov and Victor Medkov, had been watching with mounting concern as marriage and birth rates fell precipitously—this was not how capitalism was supposed to play out. But they thought they knew who could help.

They turned to Allan Carlson, president of the Illinois-based Howard Center for Family, Religion, and Society, a historian who made his name studying family policy, earning an appointment to President Reagan’s National Commission on Children. His 1988 book, Family Questions: Reflections on the American Social Crisis, had set out to define and explain how a similar demographic decay—spurred by the postwar feminist and sexual revolutions—had played out in America. Medkov and Antonov read his work with enthusiasm, invited him to Moscow, and took him to meet Ivan Shevchenko—a Russian Orthodox mystic in whose Moscow apartment the WCF was hatched.

They envisioned the World Congress as a global gathering for social conservatives dedicated to protecting their vision of the family in a changing society. They soon launched plans to host their first conference in 1997 in Prague. It proved an unexpected success, drawing more than 700 participants. That year Carlson, who had raised most of the money to host the event, helped establish and became president of the Howard Center, which adopted the WCF as a core project.

WCF has since put on conferences in Europe, Mexico, and Australia that have been attended by thousands. The group has deep ties with the most powerful organizations in America’s religious right, including Concerned Women for America, Focus on the Family, and Americans United for Life. These groups and many others pay $2,500 annually to be WCF partners, and some give additional funds—Focus, the Alliance Defense Fund, and the Catholic Family and Human Rights Institute each chipped in $20,000 to help put on the 2012 World Congress in Madrid. In Russia, they’ve tapped the support of the nation’s religious right and its billionaire sponsors.

Since 2010, WCF has helped host at least five major gatherings in Russia where American evangelicals put their views before Russian audiences. At a 2011 demographic summit in Moscow, the event’s loaded two-day schedule of panels and speeches included just one 10-minute slot without an American presenter.

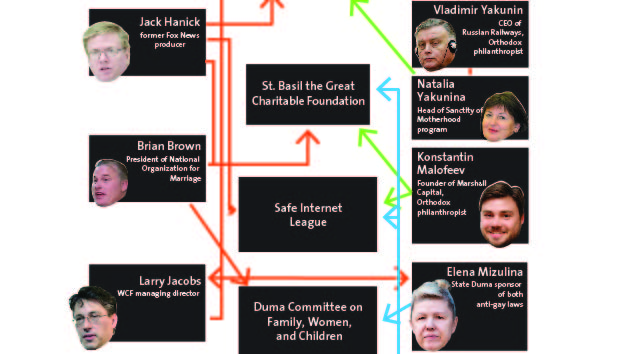

These gatherings have helped WCF’s American leaders establish tight relationships with key Russian government officials, like Duma member Elena Mizulina, the country’s foremost anti-gay legislator, who has met with Jacobs in Moscow at least three times and is a frequent attendee at WCF events. This June, National Organization for Marriage President Brian Brown, who serves on WCF’s Moscow 2014 planning committee, flew to Russia two days after the lower chamber of parliament approved her gay propaganda ban to meet with Mizulina about crafting her next piece of landmark legislation, a gay-adoption ban. They were met by another 2014 planning committee member, former Fox News producer Jack Hanick, for a round table on the topic.

WCF has lent its support to anti-gay politics elsewhere in Eastern Europe—Serbia, Lithuania, Romania—but it has had its biggest and most notable successes in Russia. Indeed, the rise of anti-gay laws in Russia has mirrored, almost perfectly, the rise of WCF’s work in the country, with 13 new anti-gay laws passed since Jacobs first traveled there. When I ask Jacobs if WCF’s work has contributed to this pattern, he laughs and says, “Yes, I think that is accurate.”

To be sure, the country was already fertile ground for WCF’s efforts: “On the issue of sexuality, its no secret that Russia is a conservative country,” says Tanya Cooper, Human Rights Watch’s Russia researcher.

Russians have increasingly adopted the kind of language the American religious right has long deployed to fight acceptance of homosexuality—terms like “natural family,” “traditional values,” and “protecting children,” with rarely a mention of the word “gay.”

“This does not seem like native Russian policy,” Cooper says. “It’s the rhetoric of homophobic activists in the States.”

A Powerful Church

But the fight is not just about what happens in Moscow. With same-sex marriage now legal in 16 American states and counting, elements of the US religious right have come to see Russia as a redoubt in a global battle against homosexuality. “The Russians,” Jacobs has said, “might be the Christian saviors of the world.”

That’s in large part due to the Russian Orthodox Church’s immense political influence. Post-Soviet Russia saw a huge revival in Orthodoxy after communism’s restrictions were lifted, and harsh new economic realities increased the appeal of the faith. By making common cause with the church and its goals, Putin has not only cast his regime’s opponents as enemies of Russian tradition, but shored up his popularity: Today, about 90 percent of Russians identify as Orthodox. The church is a marker of national identity, a source of political endorsements, and an official participant in the legislative process: In a 2009 agreement with Putin’s ruling United Russia party, the country’s top Orthodox official, Patriarch Kirill, won the right to review (and suggest changes to) any legislation being considered by the Duma. Since then, both Putin and Patriarch Kirill have stated explicitly and repeatedly that they believe in collaboration between church and state—a partnership that is helping to drive the government’s campaign against homosexuality.

Archpriest Dmitri Smirnov is one of the church’s most prominent officials, the host of a weekly TV show and the head of eight Moscow congregations. When I arrive at one of them on a rainy Sunday, mass is still ongoing. In his office, two men are setting up tripods and camera equipment. Archpriest Dmitri explains that our interview will be uploaded to his personal blog to ensure he won’t be misrepresented.

Dmitri was recently appointed to head the Patriarch’s Commission on the Family, Protection of Motherhood, and Childhood, a church body established in 2011 to influence legislators and act as a policy development shop for the Putin administration.

“We don’t even use the word ‘gay.’ We use the word ‘homosexualists,'” Archpriest Dmitri explains. “What’s ‘gay’ about it? I think it’s pretty sad, actually. We see homosexualism as a sin. And not just homosexualism, but also alcoholism, drug use, murder of people on the streets, or robbing a bank.”

The commission has worked closely with Mizuluna’s Duma committee on family policy, and confers with a variety of international organizations; of these, Dmitri says, “our main connection is the World Congress of Families.”

What can “homosexualists” birth?

To learn more about the work of WCF, I’ve arranged to meet Anatoly Antonov, the WCF cofounder, at his office at Moscow State University, one of the country’s most prestigious institutions. Antonov, who has slicked back salt-and-pepper hair and wire-rimmed glasses, pulls a book off his shelf—there are at least 10 more copies—signs it, and presents it as a gift. It is a compilation of Carlson’s essays that Antonov personally translated, got published, and now distributes to students.

Family, as Antonov sees it, is crumbling in the contraception-happy, gay-friendly West. “Today, this is Aldous Huxley’s brave new world!” Antonov says, shaking his fist. “I ask my students all the time: Can two stools give birth to something? So it is with two homosexualists—what can they birth? Nothing.”

Antonov has been influencing Russian lawmakers for decades. When Yeltsin came to power in 1991, he helped push for a formal ministry on the family. In 2010, Antonov helped draft a report advocating that Russians adopt three-child families as the norm—a position the Putin administration recently embraced. (“Putin is repeating our words,” he boasts.) Recently, he’s written academic articles backing anti-gay legislation and has spoken to Mizulina’s committee against gay adoption.

“Unlike other European countries, we refused to ratify proposals supporting adoption of children by gays,” he says. “The World Congress was happy that Putin stood up against the European governments. It’s our influence on Putin and his administration.”

The WCF’s Moscow Money man

Antonov remains influential in WCF, but today, it is one of his Ph.D. students, Alexey Komov, who is the organization’s official Russia representative, chair of its 2014 Moscow conference planning committee, and main link to several key oligarchs backing the family agenda.

Komov has an unorthodox history for a family values crusader. A former Moscow nightclub owner, Komov spent years studying yoga with a renowned guru and traveling the world—India, Tibet, Mongolia, Israel—trying out different religions. “I still know many stars, and some of the best nightclub owners,” Komov tells me when we meet. “I was liberal. I experimented. But if you do drugs or you start to be promiscuous, or this and that, it weakens you at the end of the day.”

When Komov’s guru was diagnosed with cancer a decade ago, it shattered the teacher’s faith that yoga would fend off disease. He declared yoga “satanic,” was baptized in the Orthodox Church, and became a monk. “I was at his funeral,” Komov says, tracing his decision to begin studying theology to that day. He started going to one of Archpriest Dmitri’s congregations, and the two became friends. Soon Komov was traveling in the most elite circles of the Russian Orthodoxy.

About a year after his transformation, the Russian Orthodox Church dispatched Komov to the 2010 World Congress planning meeting at the Colorado Springs offices of Focus on the Family. There, representatives from around the world presented bids to host the next World Congress. Komov brought a polished pitch for Moscow, but the group voted to give the next Congress to Madrid. “There was still a lot of mistrust of Russia,” says Larry Jacobs. “So we said, ‘Prove it to us.'” They asked him to organize a different event, and nine months later, the Moscow Demographic Summit hosted more than 1,000 attendees, many of them WCF regulars—Carlson, Jacobs, Antonov—and Americans from the religious right. The day after the summit, Mizulina introduced the first package of anti-abortion laws in Russia since the USSR’s collapse. “We just saw incredible results,” Jacobs says.

I meet Komov at Marshall, one of Russia’s largest private equity investment firms, in a Moscow complex that is part corporate suites—including outposts of Shell, ExxonMobil, and many Russian-owned oil and gas companies—and part high-end shopping mall. (A Maserati dealership borders the front entrance.) When I get upstairs, a towering blonde in stilettos leads me to one of the firm’s ornate conference rooms, where the walls are lined with sketched portraits of famous Russians—mainly old nobility and many, many Orthodox priests.

When I ask why we’re meeting here, Komov—who went to high school in London and business school in the United States—pushes back in near-perfect English: “You should not mention Marshall. I just happened to come here, but there’s no special meaning. I just have many friends.”

Those friends have proven helpful to WCF. “He has appointments, connections with the Orthodox Church and with several wealthy Russian leaders who are also Christians,” Carlson explains. Specifically, two Orthodox Russian billionaires who are footing many of the WCF’s Russia bills: Vladimir Yakunin, the president of the Russian railways and a Putin adviser (and possible successor), and Konstantin Malofeev, an Orthodox philanthropist who happens to be the founder and managing partner of Marshall, the firm whose conference room we’re sitting in.

The 42-year-old Komov seems like exactly the kind of guy you’d want running your fundraising operation: handsome, fashionable, charming, and, most importantly, a shining example of the WCF credo: married, a regular churchgoer, and father of to five kids.

“As Russians, we want to warn people in the West of the dangers of this new totalitarianism,” he says. “There are influential lobbies that want to promote an aggressive social transformation campaign using LGBT activists as the means. We see it as the continuation of the same radical revolutionary agenda that cost so many lives in the Soviet Union, when they destroyed churches. This political correctness is used and will be further used to oppress religious freedoms and to destroy the family.”

Komov’s own organization, FamilyPolicy.ru, is an official partner of the WCF, and has emerged as a key nexus for family organizing in Russia. In 2012, Komov and a FamilyPolicy colleague were invited to plan a family values forum hosted by Elena Mizulina; In September of the same year, she asked FamilyPolicy.ru for their comments on a draft bill making it easier for the state to monitor households with children for “conditions that negatively affect their behavior.”

On top of his jam-packed advocacy schedule, Komov is the founder and director of Integrity Consulting—he calls it “a little McKinsey”—which offers a variety of services, from business development to market research, to big-time clients like Gazprom, Phillip Morris, Sprint, JP Morgan, and a slew of other US companies. Larry Jacobs is a partner, though he says he draws no salary, describing the title as a flourish to signal financial expertise when he and Komov consult with family values startups outside of Russia.

Which brings us to the finances of the WCF. IRS documents from 2011 show that the Howard Center, the WCF’s parent organization, has a budget of just $650,000. According to Jacobs, only $180,000 of that goes to WCF. As a shoestring operation, Carlson says, the WCF has long relied on outside funding for its conferences.

Malofeev has pledged to pay for two-thirds of the 2014 World Congress, which will be held in Moscow this September. He funds the largest Orthodox charity in Russia, the St. Basil the Great Charity Foundation, which has an annual budget of more than $40 million. He also owns a 10 percent stake in Rostelecom, Russia’s largest telecommunications company and a Sochi Olympics general partner. In recent years, Malofeev has called for conservative versions of Facebook, Wikipedia, and Google, while his advocacy campaign, the Safe Internet League, has pushed to limit Russian internet users’ access to everything but a group of preapproved sites. (Three major Russian mobile providers have joined the league, as has the CEO of the country’s largest web portal. )

Arguably even more powerful is Yakunin. He’s old friends with President Putin dating back to their work with the Gorbachev administration in the ’80s—Putin with the KGB, Yakunin as a diplomat. As head of the state railways, Yakunin has overseen $7 billion worth of Olympic infrastructure initiatives; of the roughly two dozen projects, the most expensive was a now-infamous $8.7 billion road that, Russian Esquire calculated, would have been cheaper had it been paved with caviar.

Yakunin helped pay for the WCF’s 2011 Moscow Demographic Summit, and his fortune has funded a variety of Orthodox charities supporting the family movement. Back in 2009, he gave $50 million to start an endowment for the Russian Orthodox Church. This past spring, Yakunin launched another endowment fund to generate capital for three organizations—two of his Orthodox charities, and the Sanctity of Motherhood group, whose board is chaired by his wife Natalia.

“Welcome to Russia”

When I attended the third annual Sanctity of Motherhood conference at the Moscow headquarters of RIA Novosti (one of Russia’s main news agencies) in November, WCF’s Russian allies were all in attendance—the Yakunins, of course, as well as Komov, Antonov, and Archpriest Dmitri.

In one of the four auditoriums, Elena Mizulina was speaking about the need for government regulation to ensure pro-family messaging in media. Upstairs, in the largest hall, Jack Hanick, the former Fox News producer, gave a talk.

“Some of the world thinks that the definition of family is changing,” Jacobs said from the stage during the closing ceremony. “But I have good news. As God created, the family has been, is now, and forever will be the same!”

And the WCF is doing its part to make sure that is the case—in ever bigger and better venues. The first day of the 2014 Congress, September 10, will be at the Kremlin, before the delegates return to the place where all of this began in 2010—Moscow’s Christ the Savior Cathedral. Like-minded advocates from around the world will attend a parliamentary forum at the Duma with Mizulina, a workshop on Russia’s propaganda law, and a session on developing pro-family legislation. The day after the conference, delegates will be bused an hour and a half to visit Trinity Sergius Lavra, Russia’s most important monastery, where there are plans for a dinner served by some 300 monks.

The WCF and its Russian allies will no doubt be celebrating. Since the first time they held this gathering a mere four years ago, family policy in Russia has been transformed: Mizulina helped pass the first package of anti-abortion legislation since the USSR’s collapse, and her duo of laws stifling gay rights passed unanimously in both houses of parliament. This month, the administration further tightened her original adoption ban with a series of technical amendments. A bill to separate gay parents from their children, shelved as the Olympics drew closer, is widely expected to be reintroduced after the world’s gaze moves on.

Meanwhile the opponents—”the homosexualists”—have receded from public view, holding hands less, getting beat up more, assembling fewer and smaller protests, and contemplating emigration in rising numbers. In just four years, due in no small part to the WCF, the family in Russia has become increasingly “natural.”

“The world is already looking at Russia as you’re hosting the Olympics,” Jacobs says pacing back and forth on stage during the closing ceremony of the Sanctity of Motherhood gathering, his voice rising. “Everyone will be watching. Everyone. Now in 2014, after the Olympics are over, they have a chance to watch what you will do to support families. And we need all of you to fill up that Kremlin hall with 5,000 people. So that you can say to the rest of the world: ‘Welcome to Russia!'”

This article was made possible by an exchange sponsored by the International Center for Journalists.