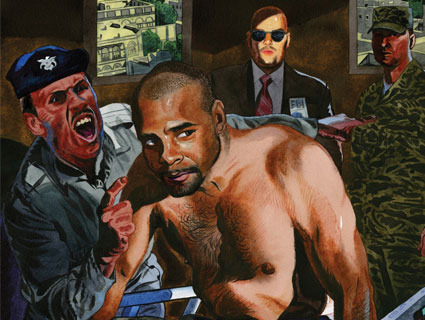

Naji Mansour is just the latest American citizen to claim that the US government orchestrated his detention abroad. Since 2003, at least eight other men have come forward with similar allegations. The circumstances vary, but their experiences often share a few common threads: They say they were pressured to become FBI informants and, in some cases, told their names had been placed on the no-fly list and they couldn’t return home until they answered the bureau’s question. Some allege their American interrogators denied them access to legal representation. Others claim their foreign captors tortured them, and the US government knew of or cooperated with the abuse. Dozens of other Muslim Americans—including four who are the plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed against the government last week—were not detained, but say the government put them on the no-fly list to pressure them into talking to the FBI or working as FBI informants. No one has a complete tally of these cases, because the government refuses to discuss them. But here are eight that have come to light. In six of these cases, the detainees were also told they had been placed on the no-fly list; four of the detainees allege they were asked to become FBI informants, and seven say they were questioned by the FBI before or during their time behind bars overseas.

Ahmed Omar Abu Ali (Falls Church, Virginia)

Arrested by Saudi Arabia in June 2003, Abu Ali was held for more than 20 months without charge, trial, or access to a lawyer. Abu Ali’s family sued the US government on his behalf, arguing that the Saudis had jailed and interrogated him at the FBI’s behest. When a judge allowed the case to go forward, the Saudis released Abu Ali and extradited him to the US, where he was charged with providing material support for terrorists and conspiring to assassinate President George W. Bush. He was convicted based largely on a confession he gave in Saudi custody—a confession he and his lawyers said was extracted via torture. He’s currently serving life in prison.

Amir Meshal (Tinton Falls, New Jersey)

A joint US-Ethiopian-Kenyan task force arrested Meshal near the Kenyan border in early 2007 as he fled the US- and Kenyan-backed Ethiopian invasion of Somalia, where Meshal had moved with his family to live under Islamic rule. He was later transferred to prisons in Somalia and Ethiopia, where he was held incommunicado for four months. He alleges he was interrogated by FBI agents in foreign custody and denied access to a lawyer. He maintains he has no connection to terrorism and in 2009 sued the agents involved in his ordeal, alleging that his detention and interrogation violated the Constitution and the Torture Victims Protection Act. The case is ongoing.

Daniel Maldonado (Pelham, New Hampshire)

Like Meshal, Maldonado had moved to Somalia with his family. While fleeing the Ethiopian invasion in January 2007, he was arrested and detained by the same international task force that picked up Meshal. After FBI agents questioned him in Kenyan custody, he was eventually handed over to the US and in April 2007 pleaded guilty to material support for terrorism—he says to avoid explosives charges. He was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison.

Sharif Mobley (Buena, New Jersey)

Mobley alleges he was kidnapped and shot by Yemen’s secret police in 2010 while he was living in Sana’a, the country’s capital, where he had moved with his family. FBI documents confirm that agents interviewed Mobley while he was being held in a Yemeni military hospital—even as other US officials were telling Mobley’s wife that the US government didn’t know his whereabouts. Mobley claims he was regularly interrogated and tortured while in Yemeni custody. After several weeks in detention, he attempted to escape from the military hospital, allegedly shooting and killing a guard in the process. According to his lawyer, he recently disappeared from the Yemeni prison where he has been held since the escape attempt. The Yemeni government says he remains in its custody, but his lawyer hasn’t had access to his client and fears he’s being tortured.

Naji Hamdan (Los Angeles, California)

Hamdan was arrested and detained in the United Arab Emirates in August 2008, six weeks after being interviewed by the FBI at the US Embassy there. He says his Emirati jailers beat him and alleges that the US government directed his interrogations and was aware of the abuse. The UAE detained Hamdan in secret for three months, then transferred him to its regular prisons. In September 2009, the UAE convicted Hamdan of support for terrorism-related activities, sentenced him to time served, and deported him. He maintains his innocence; the US government never charged him with any crime. In 2010, he sued the government under the Freedom of Information Act, seeking documents and information about his case. The case is ongoing.

Yusuf Wehelie (Fairfax, Virginia)

Yusuf and his brother Yahya were stopped by Egyptian authorities at the airport in Cairo on their way back from Yemen in 2010 and told they couldn’t return home until they spoke to the FBI. After the brothers met with the FBI at their hotel, Yusuf was told he could fly home. But he says that when he returned to the airport, Egyptian authorities arrested, interrogated, and beat him, asking him the same type of questions the FBI had asked the day before. Wehelie says his Egyptian captors “stated over and over that they worked for the United States government, and that they were questioning me at the request of the United States government.” He was released after several days and flew home; his brother was allowed to return several months later.

Yonas Fikre (Portland, Oregon)

Fikre was arrested in the United Arab Emirates in 2011 a few months after refusing to become an FBI informant. He was held for three months before being released without charges. He now lives in Sweden, where he is seeking political asylum. After he took his story to the press, the US government charged him in asbsentia with conspiring to evade reporting requirements for large money transfers; those charges have since been dropped.

Gulet Mohamed (Alexandria, Virginia)

After traveling to Yemen and Somalia, Mohamed alleges he was arrested at Kuwait’s International Airport in December 2010 and held at a secret Kuwaiti-run prison. After being held incommunicado for over a week, he was released to a deportation facility, where he called the New York Times to tell the paper his story. He was allowed to return to the US in late January 2011 and never charged with any crime. That April, he filed suit against the US government alleging his constitutional rights had been violated. The case is ongoing.