Woodson: <a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/12998394363/in/photolist-kNCaMD-62LAUF-5kLcuC-b6Ms8p-3db8TB-5kLcom-6X2Tfh-5kLcjG-4cKrbQ-5Czz7W-AAwed-9Zxy3a-ceda9s-4wBQf1-fu1u1W-7taZs9-ankGvu-anhUbp-aytyzF-av8xto-7rSPag-da8sSM-3dbdvM-aALoMQ-7t77V6-aywvJf-8eFrkg-b6Msm6-3dap6z-3dfscQ-9mAFc1-6yrREA-3oesKi-9mAEL3-62Qbbu-4xsdKV-6yrQTL-hMaR5G-dc6YRU-7taUKA-3daz3r-5UPiLa-dYWX2x-ejnaHr-ejsU9L-ejsTX9-ejsU29-4F1MmK-ejnbH4-ejsUdL">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr; Ryan: <a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/12987500003/in/photolist-cY7LjU-d2XTNq-cY7VMu-6fVNHj-9ijMDs-9igGKF-cQUX2u-djYFKV-6ePeoZ-6eTpsj-6ePeKM-6ePewc-divpTT-64NPZF-kME2Sc-kMEkgR-kMDkLn-64NQKT-d2AJVU-cSN483-kMDvhr-kMDAXV-kMDCK2-kMEnfF-kME84z-kMEcQZ-mBuBf-9ijMUu-kMEp3t-6fRBUr-d3bnvu-d39mhS-cPUMDJ-kMDLf2-kME51R-kMDz5M-kMDNiv-kMDtwx-4nmhC2-kMExuP-d2vsiw-dVwbN6-d3bnff-cQmA41-cQy6bu-cQy7B5-cQmyGu-cQmzmd-cQyaDm-cQy8LQ">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

Last month, after Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) blamed a “culture problem” in America’s “inner cities” for the nation’s intractable poverty epidemic, he was accused of racial dog whistling. Ryan later apologized, calling his comments “inarticulate,” and last week he met with the Congressional Black Caucus, where he reiterated his apology. But the episode undermined Ryan’s year-and-a-half long effort to fashion himself into the leading Republican voice on poverty. And it begged the question of what Ryan—whose budgets have consistently called for steep cuts to social safety net programs—had actually learned during the national “listening tour” of low-income communities he had embarked on following his failed vice presidential bid.

His guide—and guru—on this journey has been a former civil rights activist and prominent African-American conservative named Robert Woodson Sr., who has devoted his life to trying to help low-income people help themselves.

“What he said was true,” Woodson says of Ryan’s “inner cities” comments, though he adds, “I would not have advised him to say it.” Such remarks don’t go over well, Woodson notes, when they’re made by people who don’t have much of a track record helping the poor.

Ryan may not be able to publicly make such comments about some of the residents of low-income communities, but Woodson can—and has been for years. Lanky and spry at 77, he’s the founder of the DC-based Center for Neighborhood Enterprise, which works with faith-based and community groups to help them flourish. Unlike Ryan and other conservative critics of federal poverty policy, he has plenty of street cred. In the past, Woodson has worked in the trenches brokering gang truces and championing tenant ownership of public housing projects.

He believes that what’s obstructing progress on poverty isn’t a lack of money but a lack of fresh ideas, as he testified last week before Ryan’s House Budget Committee during a hearing on the legacy of the war on poverty. “The compassion for the poor can not be defined by how much we spend on them,” he said. He’s not opposed to spending money on the poor—but he is against funding federal programs he thinks waste taxpayer dollars by not producing results or by encouraging dependency.

Woodson’s outsider views on government and poverty have led him in certain cases to embrace unconventional and occasionally controversial programs. And Woodson has been encouraging Ryan to learn from some of these groups.

Woodson has been called one of the godfather’s of President George W. Bush’s faith-based initiative, which Woodson helped inspire when Bush was still governor of Texas. In the tradition of Booker T. Washington and other champions of African-American self-reliance, Woodson is a conservative who believes in the need for low-income and minority communities to help themselves. He thinks that the real source of social ills like crime, substance abuse, or out-of-wedlock births isn’t racism, poverty, or inequality but rather moral failings.

Ryan has been crossing paths with Woodson since he was 22, when they both worked in various capacities with Jack Kemp, the Republican congressman from New York who dubbed himself a “bleeding heart conservative” and who was known for his outreach to minority communities.

Ryan reached out to Woodson in October 2012 as his vice presidential ambitions were imploding. Mitt Romney’s infamous “47 percent” comments, denigrating nearly half the country as moochers on the government dole, were dominating the headlines. And those remarks were merely the capstone of a campaign that had experienced a number of cringe-worthy moments surrounding issues of inequality and the poor.

Since late 2012, Woodson has introduced Ryan to grassroots leaders around the country who are running programs that Woodson believes hold the key to solving the problems plaguing America’s poor communities. Together, they have toured anti-violence programs in Milwaukee, drug-treatment centers in San Antonio, and foster care placement programs in Somerset, New Jersey.

Woodson believes that traditional, governmental approaches to poverty—such as welfare and federal disability—harm the people they’re trying to help. He maintains that’s because the government relies on elitists who claim to know what’s best for the people they serve. “We must be open to accept a new brand of ‘experts’ whose authority lies in their effectiveness rather than in professional accreditation or advanced academic degrees,” he wrote in his 1998 book, The Triumphs of Joseph.

The concept sounds good in theory, especially to Republicans who are ideologically opposed to entitlement programs and government bureaucracy. But Woodson’s anti-elitist worldview has led him to champion some offbeat “experts.” One of them is Shirley Holloway, who testified alongside Woodson last Wednesday.

Holloway is a fourth-generation minister and former US Postal Service employee who preaches at her own non-denominational church in Maryland. She runs several faith-based programs aimed at drug addicts, the homeless, and domestic violence victims. Ryan visited her Washington, DC-based residential program in November. Her ministry doesn’t rely on mental health professionals, but it does entail faith-healing of the variety she performed on this crippled woman in Uganda:

Holloway told me that her programs have served 50,000 people since 1995, with an 85 percent success rate among those who stick it out. (Up to a quarter, she says, drop out of the program. Conventional treatment programs have a 40 to 50 percent rate of success at keeping people clean for at least a year.) Holloway’s statistics aren’t based on hard science, though. She told me they were calculated by interns who had helped go through her records.

Many of the programs Woodson has introduced Ryan to have a strong, charismatic religious component. This includes a men’s “boot camp” Ryan recently visited, which is run by Indianapolis’ Emmanuel Missionary Baptist Church. In this case, “boot camp” stands for “Because Of Others Testimonies Christ Answered My Prayer,” and the program focuses on marriage counseling, drug treatment, and job training. Ryan called it a “blueprint” for “rebuilding men.”

“The people our groups deal with are at the bottom end,” Woodson says, explaining why so many of his stops on the Ryan listening tour involved religious groups outside the traditional faith-based charitable networks like Catholic Charities or Lutheran Social Services. “These are people who prison couldn’t change, conventional therapeutic intervention didn’t work for. Their problems were essentially a moral or spiritual crisis. There’s an absence of spiritual meaning. What my groups have found is that faith is the only thing that helps to restore the people that they serve.”

Woodson think the federal government should encourage faith-based programs by allowing people to use taxpayer-funded vouchers to pay for their services and also by exempting these outfits from licensing requirements and other regulations. But some of the operations he has championed seemingly show the need for more oversight, not less. Among them is an organization called Teen Challenge, a drug and alcohol recovery program associated with Assemblies of God, a Pentecostal denomination whose services feature parishioners speaking in tongues.

Teen Challenge considers addiction a manifestation of sin that must be treated with religion. There have been reports of the program performing exorcisms and the internet is full of “survivor” accounts by former clients who found Teen Challenge to be little more than a form of coercive religious indoctrination.

In 1995, the Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse attempted to shutter a Teen Challenge facility in South Texas after finding a host of violations of state health and safety code regulations. In response, Woodson helped organize a protest at the Alamo. The outcry prompted newly elected Gov. George W. Bush to push through new rules exempting faith-based treatment programs from state regulations.

Not long afterward, a Dallas boy filed suit against Teen Challenge alleging that a staff member who was a convicted drug trafficker had molested him and that the program had been knowingly hiring ex-cons to work in the program. The lawsuit was dismissed, but an investigation by the Texas Department of Protective and Regulatory Services found “sufficient evidence” that abuse might have occurred but not enough to prosecute, according to the Austin Chronicle.

Teen Challenge has been plagued by other controversies as well. In 2004, the directors of the Hawaii Teen Challenge pled no contest to stealing nearly $75,000 in welfare and food stamp benefits. A year later, the US Department of Agriculture attempted to cut off food stamps to residents in several Teen Challenge programs, because they were turning their benefits over to the program directors. The USDA said because Teen Challenge wasn’t licensed, this practice violated federal rules. (Food stamps turned out to account for as much as half of these programs’ food budgets.)

Woodson again stood up for Teen Challenge. “I threatened to lead a mass picket of the Bush administration if that was not changed,” he says. The administration backed off.

Woodson defends Teen Challenge’s record, and he sees no church-state conflict in the idea of government encouraging and even funding its work through vouchers. “If people are going there voluntarily, what’s the issue?” he asks. “If you had a child who was hooked on heroin, what’s the problem? Most of the people who come to Teen Challenge…have failed other interventions.”

The programs Woodson has introduced Ryan to may be saving souls and generally doing good work, but how relevant are they to overhauling federal anti-poverty policy, as Ryan says he wants to do? Faith healing and intensive religious prescriptions don’t offer any broader clues to improving the lives of the estimated 50 million Americans living below the poverty line. The most effective neighborhood-based church program can only address a sliver of the problem. Only 4 percent of all food assistance in the country, for instance, is provided through private charitable food banks.

The focus of Ryan’s listening tour suffers from another limitation: Most poor people don’t resemble the ones served by the programs he’s visiting. Woodson is the first to acknowledge that low-income communities don’t consist solely of hard-core heroin addicts, mentally-ill homeless people, or juvenile delinquents. He recognizes that the federal safety net shouldn’t assume that every poor person suffers from chronic irresponsibility, character flaws, and spiritual deficiencies. Many low-income people today, Woodson acknowledges, are poor by no fault of their own and just need temporary assistance while they get back on their feet.

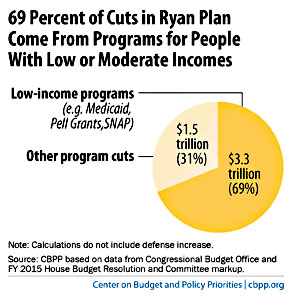

His nuanced understanding about the nature of poverty may be one reason why Woodson and his protégé don’t agree on everything—particularly aspects of the budget that Ryan recently proposed. Woodson views food stamps, for instance, as an effective anti-poverty program that works a bit like the vouchers he’s long proposed; Ryan would slash billions from food stamps over the next decade. “I don’t suggest that everything that they’re recommending I agree with,” Woodson says.

But he thinks Ryan is “evolving,” as he struggles to articulate a conservative vision of anti-poverty policy. “We need people to think of creative alternatives between people who say ‘if you care for the poor, you spend more on a variety of dependency producing programs’ and those who say ‘just cut it,'” Woodson says. “There has to be an alternative to this debate we’re having.” But is Ryan—who in the past has reduced the debate to one of “takers versus makers“—the right messenger?

“I’m not running for office, nor am I campaigning for anybody,” says Woodson. “I don’t need another politician to shepherd around, so I wouldn’t be spending this time with him if I didn’t think it would benefit the people I serve.”