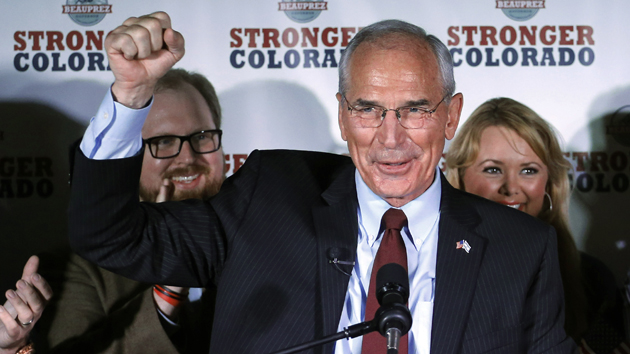

Ed Andrieski/AP

When he first ran for statewide office in 2010, John Hickenlooper, the Democratic governor of Colorado, told voters he supported the death penalty. But last year, as the state prepared to kill Nathan Dunlap, a convicted quadruple-murderer whom doctors had diagnosed with bipolar disorder, Hickenlooper said that new information—about the cost of execution, Dunlap’s mental illness, and members of the jury who had changed their minds about killing Dunlap—had caused him to change his opinion. Hickenlooper stayed the execution but stopped short of granting full clemency—thus leaving his successors with the option of ordering Dunlap’s execution at some future date. “Colorado’s system of capital punishment is imperfect and inherently inequitable,” Hickenlooper said at the time. “Such a level of punishment really does demand perfection.”

Now Bob Beauprez, Hickenlooper’s Republican opponent, is running a campaign centered on a simple promise: Elect me and I’ll kill that guy.

“When I’m governor, Nathan Dunlap will be executed,” Beauprez, a former congressman who represented Colorado’s 7th District from 2003 to 2007, promised during a GOP primary debate in May. “This is not a flippant issue,” Beauprez’s communications director said in an email, “but Bob does believe capital punishment should be an option for our most heinous crimes.”

Hickenlooper, a once-popular mayor of Denver, is now running about even in the polls with Beauprez. And although it’s unclear exactly how much Hickenlooper’s death penalty stance plays into his struggles, a poll last year found that 67 percent of Coloradans disapproved of his decision in the Dunlap case.

“It was handled very clumsily,” says Kyle Saunders, a political scientist at Colorado State University. “It was a very nuanced decision in his head, but it came off being very wishy-washy and weak.”

Dunlap has been on death row since 1996, when a jury convicted the former Chuck E. Cheese cook of murdering four of his ex-coworkers and seriously injuring a fifth. Dunlap, who had been fired, had returned to the restaurant, hid in the bathroom until closing time, and then shot his former colleagues as they were cleaning up.

Death penalty politics hadn’t played a major role in Colorado until recently. The state has only put one inmate to death since 1975, and there are currently just two other inmates besides Dunlap on death row. “We may have a bit of a bit of the west left here, but we’re not Texas,” says Norman Provizer, a political scientist at Metropolitan State University of Denver. But Hickenlooper’s trouble wasn’t just that he saved Dunlap’s life; by picking the middle-road path of sparing him just for the time being, Hickenlooper looked indecisive and unsure, an image that Beauprez has happily pushed throughout the campaign.

Hickenlooper didn’t do himself any favors when he seemed to change his decision again earlier this year. Although he hasn’t offered full clemency, he hinted in a television interview that he might move Dunlap permanently off death row if he loses reelection this fall. Beauprez’s campaign responded with a scathing web ad attacking Hickenlooper for having “stood in the way of justice.”

Beauprez hasn’t let up. “That’s the problem people have with John Hickenlooper. He can’t seem to make the tough call,” Beauprez said during a debate late last month. Death row inmates, he warned, “won’t be rejoicing when I, as your next governor, enforce the law in Colorado and see justice served.”