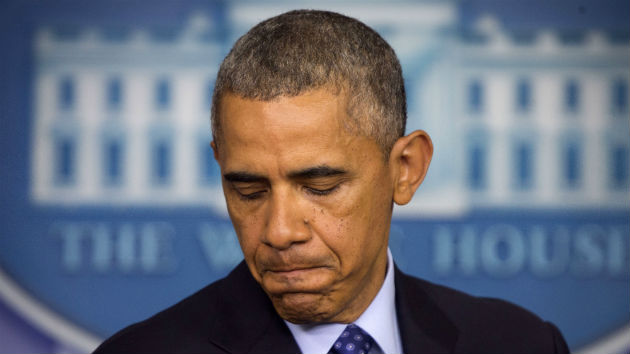

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

“We are the ones we have been waiting for.” That’s what Barack Obama proclaimed the night of Super Tuesday in 2008, borrowing the line from a 1980 June Jordan poem (without citing the poet). His aspirational emphasis on we was a foundation of the campaign that brought him to the White House. But it’s the president’s inability to find a way, while steering the nation through a series of crises, to turn that we into a reality that has brought him and his party to the darkness of Election Day 2014, when Republicans bolstered their tea-party-driven majority in the House and handily seized control of the Senate. Soon they will crown Mitch McConnell, who easily dispatched his Democratic challenger, as Senate majority leader. And imperiled GOP governors across the country—Scott Walker in Wisconsin, Rick Scott in Florida, and Rick Snyder in Michigan—vanquished their Democratic foes. Dems flamed out across the land—even as voters in red states approved initiatives to boost the minimum wage.

As president—as opposed to as candidate—Obama has not been able to engage fully the voting public. He has faced numerous obstacles—GOP obstructionism in Washington, global circumstances that yield one tough-to-resolve dilemma after another, and the rise of a profound unease and uncertainty (about now and about the future) among Americans. And Obama, like most two-term presidents, has had to confront the six-year itch that usually leads to a loss of House and Senate seats for the chief executive’s party. Still, it is partly Obama’s failure as the nation’s storyteller-in-chief to keep the citizenry—especially his voters—involved in the ongoing political narrative that afforded the GOP, a party on the wrong side of the country’s changing demographic tide and often at odds with public opinion (on the minimum wage, on gun safety, on key components of Obamacare), the chance to expand its political power.

Midterm elections are composed of individual contests, each with their own peculiarities and, frequently, odd bounces. Two years ago, what political pundit would have predicted that Joni Ernst, a slick Sarah Palin-like right-winger who called for Obama’s impeachment (and then denied she did so), would bag a Senate seat in Iowa, where Obama won reelection by 6 percentage points? Or Colorado? It elected Obama by 5 points two years ago, and it’s experiencing more job creation and a greater increase in personal income than almost every other state. Yet its incumbent senator, Democrat Mark Udall, fell to GOP Rep. Cory Gardner, a tea partier who sought to throttle back on his far-right positions.

American voters are in a funk. Even as the economy has improved—albeit slowly—after the Bush-Cheney crash of 2008, Americans have become devoutly pessimistic. In June 2009, the RealClearPolitics poll average tracker found that voters were divided equally between those who believed the nation was on the right track and those who feared it was on the wrong track, with each view being held by 48.5 percent of respondents. Since then, the right-track number has been on a long-term slide. Today, it stands at a lowly 27.8 percent. Wrong-trackers clock in at 66 percent. That’s one sour electorate. (Last month, Gallup found that 41 percent of Americans believe the economy is getting better, but 54 percent see it as worsening, despite a declining unemployment rate. This 13-point differential represents the best outlook since January, but it indicates most Americans hold a bleak view.)

When people are disaffected (or scared), they often lash out—or tune out. An October Gallup survey noted that Americans were less eager to vote in this year’s midterms than they were in the previous three off-year elections. Only 32 percent said they were “extremely motivated” to vote, compared to 50 percent in 2010 and 45 percent in 2006. But there was a great partisan divide among those looking forward to marching into the election booth. Forty-eight percent of Republicans reported they were enthusiastic about voting this year. No doubt, angry Republicans were looking forward to taking a poke at Obama and the Ds. Yet only 30 percent of Democratic voters said they were eager to cast a ballot. This suggested that Obama and his fellow Dems had, to a degree, lost their own base. With Republicans threatening to overrun the Senate—and undo the president’s achievements and more effectively than ever block policies his supporters fancied—many Democratic voters, according to this poll, were responding with a resounding…meh.

Why don’t Democratic voters have their heads in the game? Where’s that we?

It’s always been difficult to mobilize large numbers of voters outside of presidential campaigns when folks who don’t pay much notice to politics are still drawn to the mano a mano combat between two candidates battling to become the alpha male (or, maybe one day, alpha female) of the nation. As Ronald Brownstein points out, Obama’s crowd, in particular, is “a boom-and-bust coalition that depends heavily on minorities and young people who turn out much less regularly in midterm than presidential elections.” Yet Obama has not accomplished a key mission: sell his own successes and keep his own (political) troops fired up and ready to go.

After the Democrats’ midterm shellacking in 2010—when tea-partyized Republicans seized the House—top White House officials acknowledged that they had flopped as marketers. Obama had racked up major policy wins in his first two years as president: a stimulus bill credited with lifting the level of employment, a rescue of the auto industry, Wall Street reform, tax cuts for about 90 percent of taxpayers, health care reform, increased Pell grants for college students, and legislation that would allow women to challenge pay discrimination in the workplace. And an economy that had collapsed was creating new jobs. But the White House had not been able to peddle these gains as outright political wins, and the tea party had thumped Democrats. In postelection conversations with his advisers, Obama observed that he had not matched what he had done so well in the 2008 campaign: tell his own story.

His aides told reporters that they got it: They realized they had screwed up one essential element of governing—defining the ongoing narrative. They vowed they had learned their lesson and would do better.

But it’s not clear that this lesson learned was processed into change. Sure, Obama, after a bruising stretch with House GOPers, who pushed for a government shutdown and provoked a debt ceiling crisis, rallied and ran an effective reelection campaign against a Republican nominee loaded with liabilities. But as soon as that election was over, he seemed to slide back toward the same problem. In part, Obama faced a structural problem. He could not vanquish Republican obstructionism on his own. The anti-government forces of the GOP were in the happy position of knowing that if voters viewed Washington as dysfunctional Obama would bear much of that taint. Republicans (many of whom don’t want government to be considered as an effective tool) would benefit from public disgust—even if their constant opposition caused the sclerosis.

And there’s this: Obama’s wins have often been nuanced or mixed, especially from the perspective of his supporters. In the lame-duck session after the 2010 elections, he won a tax package that was a mini-stimulus—but at the cost of extending George W. Bush’s tax cuts for the wealthy. His health care reform—the product of a long and ugly legislative tussle—did not include a public option, and then yielded the website fiasco. He vowed to cut back the war in Afghanistan, but okayed a troop surge first. His administration implemented a number of policy initiatives aimed at curtailing climate change—but there was no grand gesture (say, an international climate treaty or comprehensive legislation). His effort to eliminate Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell was initially excoriated by gay rights advocates, who believed he was not moving quickly enough to abolish the discriminatory policy. He ended the war in Iraq—sort of. Then came ISIS and a US military re-engagement. He issued orders that protected certain undocumented immigrants—but deportations increased, and he delayed further action that would protect undocumented immigrants. He went along with GOP-pushed budget cuts to protect other spending priorities and to prevent a debt ceiling implosion. Through much of this, he had trouble presenting his side of the tale—and he was often reluctant to bash the Republicans because he believed he was obliged to keep trying to forge reasonable deals with the opposition. At times, the president did let loose on his Republican enemies, but this was done only intermittently, in specific circumstances, and Obama never developed a consistent plot line that depicted the GOP as a force of unwavering obstructionism.

Uncertain messaging, complex policy wins, compromise, and mess—it’s not a surprise that members of the Democratic coalition with tenuous ties to the political process dropped out. Hope and change had become half a loaf and complication. Meanwhile, life at home and abroad seemed to become even more crisis-riven: a health care website that didn’t function, veteran hospitals that were death traps (even though that story was overblown), Syria, Ukraine, ISIS and beheaded Americans, Ebola, and White House fence-jumpers. It would be natural for many Americans, wigged out about the economic security of the United States, to look at the president and say, make it stop, make this go away—and not care that, thanks to the guys who wrote the Constitution, Obama cannot on his own bend Washington to his will. And shaping events in the Middle East, Russia, and Africa is not any easier. His poll numbers sagged, Democratic candidates ran from him. The president and his party did not effectively present a competing story to counter the vague, fear-mongering, competence-challenging attacks Republicans mounted against Obama and his minions.

White House officials point out—as explanation or as excuse, you decide—that in today’s chaotic and cluttered media environment, it is tough for them to get a direct shot at voters. When they try to convey a message through the news media, it often doesn’t reach the masses. When they ignore the major news media, they get hammered. Referring to its messaging efforts, one Obama adviser recently told me, “We suck. We’re good during the campaign when people are focused. It’s hard when they are not.”

Obama and his team succeeded in transforming campaigning, integrating an intense focus on data and metrics with on-the-ground organizing. And they did it twice. But the president has not transformed politics. To beat back the expected oppositional waves of 2010 and 2014, he needed a playbook as unconventional, imaginative, and effective as those he used in 2008 and 2012. He needed to keep show-me independents on his side and Democratic-leaning voters, particularly those who otherwise would be unconcerned with politics, somehow engaged in the process. And he had to do this while presiding over a Washington that seemed to be a miasma of disorder and while contending with a troubled economy and all hell breaking loose overseas. He needed to keep the we in the mix.

Perhaps that was too tall an order. Perhaps Obama could not do this on his own. Perhaps it is nearly impossible for a president and his aides to govern well in difficult times (crafting complex and often not fully satisfying responses to knotty problems at home and abroad) and promote clear political messaging that consistently cuts through the chaff and connects with stressed-out voters freaked out about the future. Yet elections work…for those who use them. And angry Republicans have once again taken advantage of Democratic disaffection, disappointment, apathy, or whatever. Now, in part because Obama could not convince voters in Iowa, Colorado, and elsewhere to stick with him and the policies he champions, many of his accomplishments are at risk, and the nation faces the prospect of more gridlock and chaos in Washington. But Democrats ought not to blame him alone. When it comes to saying who is at fault, they need to say, “We are.”