Alex Brandon/AP

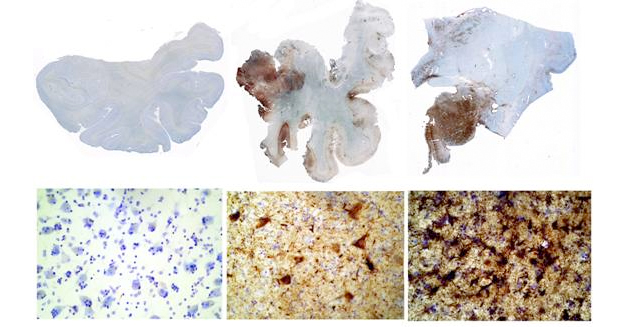

A new joint study by the US Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University found that 87 out of 91 former NFL players who donated their brains for examination showed signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the degenerative brain disease also known as CTE. The report out of the nation’s largest brain bank, which received a $1 million research grant from the NFL in 2010, supports prior research suggesting that playing football could have long-lasting neurological effects over the course of an athlete’s life.

As reported first by Frontline:

In total, the [Boston University] lab has found CTE in the brain tissue in 131 out of 165 individuals who, before their deaths, played football either professionally, semi-professionally, in college or in high school.

Forty percent of those who tested positive were the offensive and defensive linemen who come into contact with one another on every play of a game, according to numbers shared by the brain bank with FRONTLINE. That finding supports past research suggesting that it’s the repeat, more minor head trauma that occurs regularly in football that may pose the greatest risk to players, as opposed to just the sometimes violent collisions that cause concussions.

CTE can only be accurately identified posthumously, and it’s important to remember that many of the ex-players who donated their brains to BU did so because they thought they might have the disease. Still, the results are more bad news for the NFL, which for years has been criticized over its handling of concussions and brain research. The league has long denied a link between the sport and long-term brain disease—in its annual health and safety report, the league reported a 35 percent decline in concussions in the course of two regular seasons—but in April it gained approval for a $1 billion settlement with about 5,000 retired players, resolving concussion-related lawsuits. (The Will Smith film Concussion, which recounts the story of the doctor who first discovered CTE in the brain of a former NFL player, debuts on Christmas.)

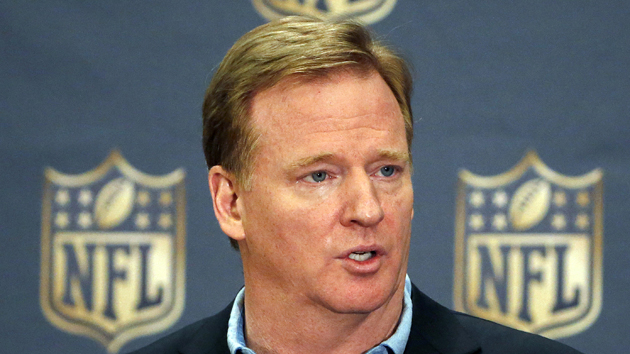

An NFL spokesperson said in a statement to Frontline on Friday: “We are dedicated to making football safer and continue to take steps to protect players, including rule changes, advanced sideline technology, and expanded medical resources. We continue to make significant investments in independent research through our gifts to Boston University, the [National Institutes of Health] and other efforts to accelerate the science and understanding of these issues.”

Dr. Ann McKee, who is the chief neuropathologist at the brain bank, told Frontline: “People think that we’re blowing this out of proportion, that this is a very rare disease and that we’re sensationalizing it. My response is that where I sit, this is a very real disease. We have had no problem identifying it in hundreds of players.”