Don’t look down. Therese Taylor repeats this mantra when she’s rising out of bed in the morning. Don’t look down. She says it when she’s standing in the shower. She says it when she’s brushing her long brown hair so that it hangs over the vacant space once occupied by her left breast. Don’t think about what you’ve lost.

She’s lost so much. Her breast. Her identity as a healthy person. Her uncomplicated sex life. Her faith in the medical profession.

Taylor has gained something too—a fury that’s uncomfortable to express when other women are dying from breast cancer and her doctors tell her she’s lucky. But when she thinks of the fear her three children endured and the months of post-surgical shoulder pain so sharp that she worried a tumor had invaded her bones, the 55-year-old Mississauga, Ontario, resident doesn’t feel lucky at all. She feels rage. Her doctors implied she had cancer and said that if she cut off her breast, she would live. Now she knows it was never that simple.

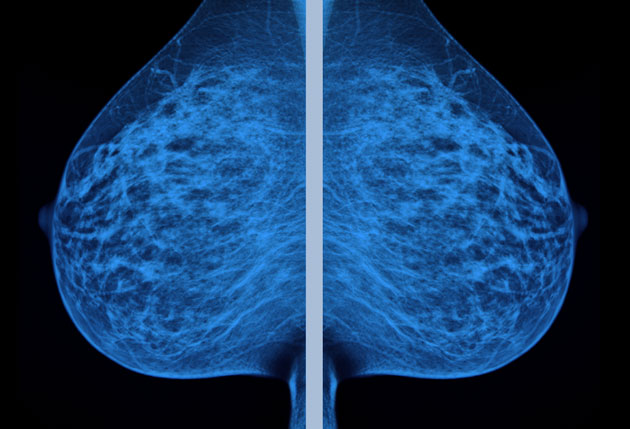

No one—not her physician or her surgeon or the pathologist or nurse or anyone else—ever took the time to explain what her mammogram and biopsy had found.

Despite what her doctor said (“It’s indicative of cancer”), the fact was that the abnormality on Taylor’s mammogram—ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS— is not considered a cancer by many experts, and it had only a small chance of ever progressing into an invasive cancer. The probability that it would kill her was even slimmer, about 3 percent. The thing in her breast was not a ticking time bomb, and were it not for the mammogram, she probably never would have known it was there.

If she knew then what she knows now, Therese Taylor would have refused the surgery. In fact, she would have canceled the mammogram. Taylor has come to realize that she lost her breast out of fear, not out of caution. She’s learned that her mammogram was at least three times more likely to get her diagnosed and treated for a cancer that never would have harmed her than it was to save her life. But perhaps the most infuriating thing she’s learned is that scientific evidence for the harms of mammography has been available—published in medicine’s most highly regarded journals—for decades.

What scientists know and Taylor didn’t is that mammography isn’t the infallible tool we wanted it to be. Some things that look like cancer on a mammogram (or the biopsy that comes afterward) don’t act like cancer in the body—they don’t invade and proliferate in other organs. Some of the abnormalities breast screenings find will never hurt you, but we don’t yet have the tools to distinguish the harmless ones from the deadly ones. And so these medical tests provoke doctors to categorize lots of merely suspicious cells in with the most dangerous cancers, which means that while some lives are saved, even more women end up with treatments they don’t need. Whether the chance of benefiting from a mammogram is worth the risks of having one is an individual woman’s decision, but Taylor believes her doctors owed her a truthful discussion about the potential harms before she made her choice.

Over the last 25 years, mammography has become one of the most contentious issues in medicine. The National Cancer Institute lit a firestorm in 1993 when, after finding sparse evidence of benefits, it dropped its recommendation that women in their 40s get screened. Since then, most of the debate has remained focused on what age women should start getting mammograms, and the number of women mammograms help. Now, after more than 30 years of routine screenings, some experts are raising a different, perhaps less comfortable question: How many women have mammograms harmed?

If you include everything, the answer is: millions. Mammograms do help a small number of women avoid dying from breast cancer each year, and those lives count, but a 2012 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine calculated that over the last 30 years, mammograms have overdiagnosed 1.3 million women in the United States. Millions more women have experienced the anxiety and emotional turmoil of a second battery of tests to investigate what turned out to be a false alarm. Most of the 1.3 million women who were overdiagnosed received some kind of treatment—surgical procedures ranging from lumpectomies to double mastectomies, often with radiation and chemotherapy or hormonal therapy, too—for cancers never destined to bother them. And these treatments pose their own dangers. Though the risk is slight, especially if your life is on the line, a 2013 study found that receiving radiation treatments for breast cancer increases your risk of heart disease, and others have shown it boosts lung cancer risks too. Chemotherapy may damage the heart, and tamoxifen, while a potent treatment for those who need it, doubles the risk of endometrial cancer. In a 2013 paper published in the medical journal BMJ, breast surgeon Michael Baum estimated that for every breast cancer death thwarted by mammography, we can expect an additional one to three deaths from causes, like lung cancer and heart attacks, linked to treatments that women endured.

More and more women are beginning to speak up about this inconvenient reality. Tracy Weitz, a women’s health researcher at the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, has publicly shared the story of her mother, Diane Olds, who died 10 days after being diagnosed with an aggressive endometrial cancer that Weitz feels may have been caused by tamoxifen treatments for DCIS. In an Elle magazine story in June, Duke University breast surgeon Shelley Hwang described the “terrible feeling” that overcomes her every time she’s asked to perform an elective double mastectomy on a woman with DCIS who “almost certainly” would have lived a long life without the procedure. In 2013, journalist Peggy Orenstein, once a staunch defender of mammography, wrote in the New York Times Magazine, “I used to believe that a mammogram saved my life,” but 16 years after a breast cancer diagnosis, “my thinking has changed.” Having read the latest studies, she wondered, “How much had my mammogram really mattered?”

Find it early; save your life. That has long been the dominant message behind mammography campaigns, and it’s a story that offers comfort—here’s something you can do to protect yourself from a truly scary disease. This message assumes that finding an early-stage breast cancer equates to preventing a breast cancer death, and if that were true, having a mammogram would be the only reasonable choice, because finding it early is what mammography does best. But at the same time that this message was becoming entrenched in our consciousness and our policies, scientific evidence was pouring in to show that it was deeply flawed. To understand why, you need to know a bit of cancer biology.

When breast cancer becomes lethal, it’s usually because it has metastasized, or spread tumors around the body. When the first screening programs were launched 30-plus years ago, most doctors reasonably assumed the disease progressed in a predictable, stepwise manner, such that every tumor grew steadily in size until it invaded other parts of the body. If all cancers behaved like this, finding and treating small tumors early in this progression would allow you to prevent them from spreading and killing you.

It’s an alluring story unraveled by the facts. Scientists now understand that breast cancer is not one disease—it’s many, and different types can behave in a variety of ways. You can think of these behavior patterns as animals you’re trying to keep in a barnyard, says H. Gilbert Welch, a professor of medicine at Dartmouth College. Some cancers act like turtles, moving too slowly to ever pose an escape risk and thus never causing any harm or requiring treatment. Other cancers, studies have shown, will actually regress and disappear on their own: Those are the dodos. And then there are the rabbits—cancers that can hop away and cause damage elsewhere in the body but are stoppable if you catch them in time. Finally, you have the birds, the deadliest cancers, which fly away no matter how hard you try to capture them.

Under the barnyard model of breast cancer, early detection becomes a weak tool. The harder you look—whether by self-exam or a traditional, digital, or 3-D mammogram or another test—the more cancers you’ll find, but most will be harmless dodos or turtles that will never threaten anyone’s life. Birds send out cancer cells before they can be detected, so women with these deadly cancers aren’t helped by mammograms either. That means screenings can only make a difference for “rabbit” cancers, which account for less than 30 percent of breast cancers?.

Thirty percent still sounds like a lot, but it’s informative to look at the numbers: A screening mammogram has six potential outcomes. Imagine that 10,000 women have annual mammograms for 10 years, starting at age 50 (women younger than 50 have fewer lives saved and more false positives, and more of them face overdiagnosis); according to an analysis published in JAMA last December of just that many women, most will receive a false positive—6,130 women will get called back for more testing for something a doctor ultimately deems not to be cancer. Another 3,568 women will have only normal, or “clean,” mammogram results over the course of that decade. Finally, 302 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer. Out of those women, 173 will survive the cancer, regardless of whether they were screened; 62 of them will die despite the screening; 57 women will be diagnosed with a cancer that would have never hurt them; and 10 women will avoid dying of breast cancer, possibly because they got a mammogram.

There’s no doubt that mammograms find lots of cancers, but the conundrum we’re up against is that we currently have no sure way to distinguish rabbits from turtles, dodos, and birds. When your doctor finds something on a mammogram, there’s no way to know whether you’re the 1 in 1,000 women whose life is at stake, or one of the 5 or 6 in 1,000 women with something that would have remained harmless. Without that knowledge, we are left with the question of what to do. Researchers are trying to find out how to distinguish the types of breast cancers, but in the meantime our reaction is to treat anything we find. If you’re the woman who’s just been told she has something lurking in her breast, removing it (and maybe the other breast too) may feel like the only safe option. The impulse to “just get it out” is a natural reaction, and it may be the right one for some women, but before they make that choice, they need to know how their individual risks stack up.

The good news is that fewer women are dying of breast cancer than they were 30 years ago, and studies suggest that’s because treatments have gotten a whole lot better. Over the last three decades, breast cancer death rates fell 28 percent among women 40 years of age or older, and they dropped 42 percent among women younger than 40, even though most of them had never been screened. An analysis published in the New England Journal of Medicine in November 2012 calculated that most of the decline in breast cancer deaths over the last 30 years was due to the development of newer treatments such as tamoxifen and targeted chemotherapy and radiation. When they work, these treatments can even stop cancers that have become big enough to feel or are causing symptoms like pain, says Welch, one of the study’s authors (which can explain those 173 women out of 10,000 who survive cancer regardless of whether they are screened). All of this suggests that early detection on a mammogram makes little difference in the outcome.

America’s age of mammography began in 1977 with the Breast Cancer Detection Demonstration Project, which invited women older than 50, along with younger women with a personal history of breast cancer or a mother or sister with the disease, to come in for screening. The program wasn’t a randomized trial or a rigorous study, but women who took part seemed to fare better than average, and this helped set the stage for a new era of mass screening and form the basis of recommendations. Two early trials, one in New York and the other in Sweden, suggested that mammography could reduce breast cancer deaths by about 30 percent.

But since then, studies with more rigorous designs have found far smaller mortality benefits from screening. Last year, results from a 25-year follow-up of two landmark Canadian studies tracking about 90,000 women concluded that mammography did not reduce breast cancer deaths at all. A study published in July examining rates of diagnoses and deaths in counties across the United States, likewise, found that areas with higher rates of screening had more cancer diagnoses but no fewer deaths overall.

Earlier this year, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released a draft of its latest recommendations on breast cancer screenings. The Task Force analyzed existing studies about mammography to create scientific recommendations. As they had advised back in 2009, the panel recommended biennial mammograms for women between the ages of 50 and 74 years. For women between the ages of 40 and 49, the group advised that the decision to screen or not should be an individual choice, based on a woman’s values and risk factors. There’s a reason so much of the debate about mammography has centered around women in this age group—for them, mammograms’ benefits are so small that researchers have dared suggest they might not outweigh the harms.

Breast cancer is an emotional issue. Most of us know someone with the disease, and some of us have lost loved ones to it. Were this discussion about a less charged subject, the Task Force’s decision to prioritize individualized decision-making might be greeted as good news for women. Instead, Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Fla.), a breast cancer survivor, called the draft guidelines “a dangerous step in the wrong direction” and vowed to fight the “misguided” recommendations.

In April, I called Wasserman Schultz to talk about the guidelines. She told me that the Task Force’s refusal to recommend mammography for all 40-year-olds would lead women to “postpone paying attention to their breast health.” As she told me her own story, I began to understand why she believes this. Wasserman Schultz was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 41, shortly after a routine mammogram came back normal. The mammogram didn’t find her cancer, but it did show signs of calcifications, and that “put her antenna up,” she said: “If I had not had a mammogram at 40, when would I have felt the lump? Would I have even been looking for it?” Tests showed the lump was cancer, and a genetic screen revealed that she carries the BRCA2 gene (similar to Angelina Jolie’s BRCA1 gene), which puts her at a high risk for invasive cancers. “I was a ticking time bomb and didn’t even realize it,” she said.

Wassermann Schultz worries the Task Force guidelines will provoke insurance companies to stop covering mammograms, making the procedure available only to those with financial means. The Task Force doesn’t dictate what services insurance companies pay for, but many insurance companies look to its recommendations when making coverage decisions. Fearing that the 2009 guidelines would jeopardize coverage, Wasserman Schultz, Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.) and Sen. David Vitter (R-La.) added language to the Affordable Care Act ensuring that mammograms are covered at no cost to the insured.

The political dispute traces back to that National Institutes of Health consensus conference in 1993, which concluded that the evidence did not support routine mammography screenings for women in their 40s. Members of the NIH panel who’d developed a report about their conclusions were brought before a hostile congressional committee to justify their decision to limit what politicians viewed as a life-saving test. At the hearing, the scientists were accused of racism and sexism by politicians who, despite what the evidence showed, believed their recommendations were robbing women of hope.

Politicians saw this as an opportunity to support women’s issues, patient advocate Maryann Napoli told me. In 2009, Rep. Dan Burton (R-Ind.) even asked his Republican colleagues to wear a pink tie or shirt while they debated the health care legislation to show their opposition to the Task Force guidelines. “This visual protest will be a sign of solidarity with women across America, and it will send a concerted message that the Republican Party is staunchly opposed to rationing mammograms, or any other policy that rations health care,” he wrote in a statement.

Never mind that no one was recommending that women be denied mammograms. The Affordable Care Act was on everyone’s mind, and once the debate took an emotional turn, the science was held hostage by beliefs that, like misguided opposition to vaccines, have proven difficult to overcome.

What’s more, we currently spend about $10 billion annually on mammography in the United States, and a recent paper in the journal Health Affairs estimated the cost of false-positive mammograms alone at $4 billion per year. Mammography facilities and the people who run them stand to lose a reliable revenue stream if mass screenings are curtailed, so it’s not surprising that many radiologists have been vocal opponents of leaving mammogram decisions to women. Adoption of the USPSTF recommendations “would result in thousands of additional and unnecessary breast cancer deaths each year,” the American College of Radiology wrote in a press release.

In a 2010 commentary in the journal Radiology, radiologists Leonard Berlin and Ferris Hall wrote, “We believe that the overreaction of radiologists to this issue may be perceived as self-interested and self-serving by the public as well as by our clinical colleagues.” They noted that radiologists were beginning to sound like outliers, and they pleaded for “more understanding and less posturing and polarization, particularly on the part of the imaging community.”

With so much rhetoric flying back and forth, it can be difficult for women to make truly informed decisions. And even if a politician’s intentions are good—ensuring that the poor have access to mammography—those intentions become problematic when patients don’t have accurate information about a test’s potential outcomes. Harald Schmidt, an ethicist at the University of Pennsylvania, recently penned an editorial in JAMA about programs established by hospitals, insurance companies, and some employers that offer incentives like cash rewards or free movie tickets to women who opt for mammograms. The problem, he says, is that that these programs “unhelpfully shortcut the decision-making process.” If your doctor says it’s up to you to decide, but that you’ll get a free gift card or a $200 credit toward your deductible if you choose a mammogram, the implication is that there’s a correct choice. In some cases, he says, incentive programs are driven by quality measures that judge health care providers by the number of mammograms they do, a practice hard to square with a commitment to informed decision-making. An Australian study published in The Lancet this year found that when a decision aid tool helped women understand the risks as well as the benefits, the number of women who intended to get a mammogram fell.

But in this country, discussions between doctors and patients about the risks are usually limited to talking about the chance that she may get called back for further testing on a “false positive,” says Karuna Jaggar, executive director of the San Francisco-based advocacy organization Breast Cancer Action. Indeed, a 2013 report in the BMJ revealed that most women were unaware that mammograms routinely detect harmless early-stage cancers and anomalies like DCIS.

The energy thrown at the mammography wars is standing in the way of progress on fighting breast cancer, says Otis Brawley, chief medical officer at the American Cancer Society. “Instead of arguing about whether we should recommend this flawed test for women in their 40s, we need to find something better,” he says. There’s no question that treatments have improved, Brawley says, but too many women don’t have access to them. “The proportion of women who get adequate care, both diagnosis as well as treatment, is atrocious in this country,” he says, and the racial disparities in access to care need fixing, too. Black women are less likely than white women to be diagnosed with breast cancer but more likely to die from the disease, and free mammograms won’t close this gap—better access to treatment will, Brawley says. While legislation attached to the Affordable Care Act ensures that women can get mammograms with no cost or copay, once they get a diagnosis, full coverage may no longer be ensured. And that’s no small detail: Studies show that a breast cancer diagnosis can put a financial strain on women for years afterward.

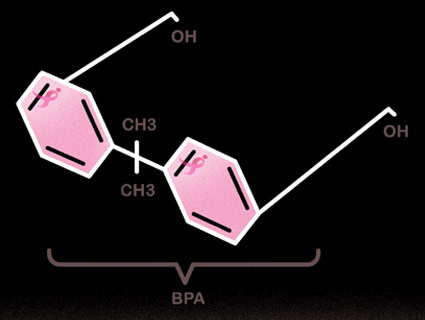

Perhaps the most striking consequence of our three decades of cancer screening is the sevenfold increase in the rate of women diagnosed with the type of abnormal cell lesion found in Therese Taylor’s breast: DCIS. Sometimes called “stage zero breast cancer,” DCIS is technically a precancer. Our best guess, based on the research available, is that about 15 percent of such lesions eventually become invasive. But that research mostly looked at DCIS detected by physical exams, not mammograms—and a lump you can feel probably behaves differently (and may be more dangerous) than a lesion that’s only detectable in an X-ray, says Barnett Kramer of the National Cancer Institute. Prior to widespread mammography, most women with these noninvasive abnormalities remained blissfully unaware of them, he says.

DCIS now accounts for 20 to 30 percent of all breast cancer diagnoses, and the adoption of digital mammography is pushing those numbers even higher. “The biggest risk factor for DCIS is having a mammogram,” explains Karla Kerlikowske, a physician and epidemiologist at the University of California-San Francisco. Aggressive treatments like surgery have become alarmingly common for women diagnosed with DCIS—from 1998 to 2005, their rate of elective double mastectomy nearly tripled, and just more than 30 percent of women diagnosed with DCIS in 2012 opted for a mastectomy, even though the vast majority of them wouldn’t ever have developed breast cancer.

When celebrity chef Sandra Lee was diagnosed with DCIS via a screening mammogram earlier this year, she shared a video diary of the experience with People magazine. Lee does not have the BRCA genes that indicate a high risk for developing cancer, but she told Good Morning America‘s Robin Roberts that both her radiologist and her doctor told her, “You’re a ticking time bomb.” Lee opted for a double mastectomy. But a study published in JAMA Oncology in August of more than 100,000 women with DCIS found that their risk of dying of breast cancer was virtually identical to that of the average woman without DCIS or any signs of breast cancer.

The trend toward aggressive treatments for DCIS worried experts enough that, in 2012, the National Cancer Institute held a meeting about the problem of overdiagnosis. The researchers discussed removing the word carcinoma from the DCIS name and renaming the condition IDLE, for “indolent lesions of epithelial origin,” to discourage unnecessary treatment and help women avoid the fear that comes with the C word. The language we have matters: In one study, Shelley Hwang, the professor of surgery at Duke University, and her colleagues presented hypothetical DCIS scenarios to nearly 400 healthy women and gave them three treatment options: surgery, drug treatment, or “watchful waiting.” When the researchers told their subjects that DCIS is a “noninvasive breast cancer,” 47 percent of the women chose surgery to remove it. When DCIS was described simply as “abnormal cells,” only 31 percent did so. Our discomfort with the words “cancer” and “carcinoma” points to a larger problem: The minute a mammogram show us something scary, the equation becomes emotional, and that usually means we go down a spiral of escalating tests and diagnoses.

Some women are opting for less aggressive treatments for DCIS, but they can’t always find support for this decision from their doctors. After Clara Haignere, a professor of public health at Temple University, was diagnosed with DCIS after a mammogram in 2013, she wasn’t too worried. One of her physicians called it a “half-ass” cancer. While researching the condition, she learned about the proposal to change the name to IDLE. She danced around her house rejoicing that she had IDLE, not cancer.

She intended to keep a watchful eye on her condition, but then her grown son sat in on a meeting in which her doctor recounted the story of a patient who didn’t get treated and had a metastasis in her brain. The message was clear: Let this be, and you could be dead. “I’m a widow, and so my son lost his dad,” Haignere told me. “It’s an issue for him on a visceral level. So how do you say no?” Her son pleaded with her until she agreed to undergo a lumpectomy. “There’s a cascade that pulls you down this slope,” she says. “They just say, ‘We’ll just do one more thing and be done with it,’ but that’s not what happens.”

Haignere’s first surgery led to a second lumpectomy, and then a third, after surgeons failed to remove the lesions as cleanly as they’d hoped. Eventually, she ended up with a mastectomy after her surgeon said it was her only remaining choice. Doctors tell her she has very little risk of recurrence, but, she says, “I lost my left breast.” When she awoke after the seven-hour surgery, she had open sores and drains sticking out of both sides of her torso that required draining every hour. “I couldn’t even get up out of bed or go to the bathroom myself,” she says, and it was months before she could finally get comfortable enough to have a good night’s sleep.

She lost a breast and six months of work, “for stage zero cancer that probably wouldn’t have killed me,” she says.

If mammography were a drug, the FDA would never approve it,” says Dr. Eric Topol, a professor of genomics at the Scripps Research Institute and editor-in-chief at Medscape, an information website for health care professionals. “We’ve crossed the line,” he adds. It’s time to rethink the way we approach breast cancer, and this new approach should be based on evidence, not fear, says Jaggar of Breast Cancer Action.

Women with a high risk of breast cancer due to a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation should absolutely work with their doctors to make a surveillance plan, Jaggar says. It’s worth noting that these mutations also impair cells’ ability to repair DNA damage, which means that women who carry these genes are more susceptible to the cancer-inducing effects of the X-rays used in mammograms and may want to rely on alternate screening tools, such as an MRI or an ultrasound.

So what should women do? “If you feel something when you’re in the shower or putting on a shirt or making love, get it checked out,” says breast surgeon Susan Love, but it’s okay to stop thinking about your breasts as enemies. “If you look at what the benefits and harms are, and you decide to have a mammogram, that’s fine,” says Fran Visco, president of the National Breast Cancer Coalition. “And if you make a decision not to get one, that’s fine too.” The National Cancer Institute provides a free risk calculator at their website, and the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium has developed an app that also incorporates breast density into the equation. Your risk increases with age—the median age at diagnosis is 61—and two-thirds (67.4 percent) of breast cancers occur in women older than 55.

After nearly 15 years of reporting on mammography, I’ve reached my fourth decade of life and made my own decision—I’m opting out of the screenings all together. The National Cancer Institute’s assessment tool shows that I’m at average risk for breast cancer, so I’d rather take the small chance that I’m missing an opportunity to avert a cancer death than face the larger risk that my life would be turned upside down by an unnecessary diagnosis. I have financial considerations, too. If a screening mammogram were to find something, it could send me down a path of more tests and possibly treatments that I don’t want and would have trouble paying for.

I want other women to make their own decisions, and when I’ve talked about my choice with friends, some have asked what I’ll do instead of mammograms. My answer is nothing, and it’s less radical than it seems. Lung cancer kills more women each year than breast cancer, as does heart disease, but no one is urging me to seek constant early detection for those. Most cases of breast cancer that respond well to treatment do so even after they’ve progressed enough to make themselves known through a symptom. Most experts now recommend simply paying enough attention to your breasts that you’ll notice if something is wrong, without becoming so compulsive that you find things that aren’t there.

If I feel a lump or notice strange changes in my breasts, like widespread redness or hardening (signs of inflammatory breast cancer), I’ll go get it checked out right away. If I develop breast cancer, it’s the biology of the cancer—not what I do or don’t do to find it—that will determine whether it kills me. So I’m letting go of the misguided notion that if I’m diagnosed with an advanced tumor it’s my fault for not finding it sooner. Instead of living in fear that my breasts are out to kill me, I’m going to relax and enjoy life while I can.