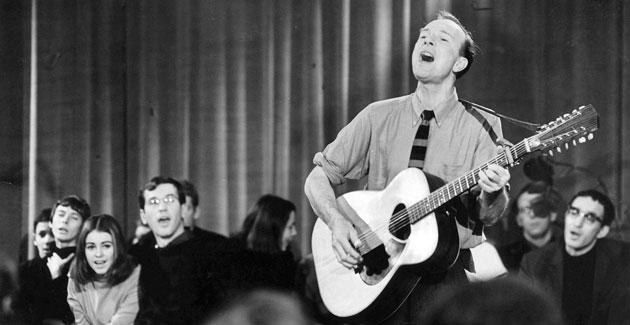

D. Steinberg/AP

From the 1940s through the early 1970s, the US government spied on singer-songwriter Pete Seeger because of his political views and associations. According to documents in Seeger’s extensive FBI file—which runs to nearly 1,800 pages (with 90 pages withheld) and was obtained by Mother Jones under the Freedom of Information Act—the bureau’s initial interest in Seeger was triggered in 1943 after Seeger, as an Army private, wrote a letter protesting a proposal to deport all Japanese American citizens and residents when World War II ended.

Seeger, a champion of folk music and progressive causes—and the writer, performer, or promoter of now-classic songs, including as “If I Had a Hammer,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” Turn! Turn! Turn!,” “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine,” “Goodnight, Irene,” and “This Land Is Your Land”—was a member of the Communist Party for several years in the 1940s, as he subsequently acknowledged. (He later said he should have left earlier.) His FBI file shows that Seeger, who died in early 2014, was for decades hounded by the FBI, which kept trying to tie him to the Communist Party, and the first investigation in the file illustrates the absurd excesses of the paranoid security establishment of that era.

In July 1942, Seeger was drafted into the Army. (“I was almost glad when I heard from my draft board,” he later wrote in a diary.) He was assigned to be trained as an aviation mechanic at Keesler Field in Mississippi. While in the Army, he kept up with the news, and in the fall of 1942, Seeger, who was then 23 years old, wrote a letter of protest to the California chapter of the American Legion. It was to the point:

Dear Sirs –

I felt shocked, outraged, and disgusted to read that the California American Legion voted to 1) deport all Japanese after the war, citizen or not, 2) Bar all Japanese descendants from citizenship!!

We, who may have to give our lives in this great struggle—we’re fighting precisely to free the world of such Hitlerism, such narrow jingoism.

If you deport Japanese, why not Germans, Italians, Rumanians, Hungarians, and Bulgarians?

If you bar from citizenship descendants of Japanese, why not descendants of English? After all, we once fought with them too.

America is great and strong as she is because we have so far been a haven to all oppressed.

I felt sick at heart to read of this matter.

Yours truly,

Pvt. Peter Seeger

I am writing also to the Los Angeles Times.

How did the American Legion respond? It forwarded Seeger’s note to the FBI in San Francisco. And somehow this matter was brought to the attention of the Military Intelligence Service of the War Department. Within weeks, military intelligence was investigating Seeger—and soon updating the FBI on its effort. The official “reason for investigation,” as numerous military reports forwarded to the FBI noted, was that “Subject wrote letter protesting and criticizing the California American Legion’s resolution advocating deportation of all Japanese, citizens or not, after the war, and barring all Japanese descendants from citizenship.”

Seeger had become a target merely because he had objected to mass deportations. The secret investigation coincided with the completion of Seeger’s training as an aviation mechanic. He expected to be deployed to active duty. But while he was under investigation, those orders never came. He watched the rest of his training class be sent to airfields, but he stayed put. At first, he wasn’t sure why. He was frustrated.

Military intelligence officers across the country began probing Seeger and his background. They searched police records in various locales (and found nothing). They discovered that a House committee had come across his name twice while investigating subversives in the pre-war peace movement. They secretly read his mail, including letters from his Japanese American fiancee, Toshi Ohta, who was living in New York City. The investigators were concerned that Ohta was working for the Japanese American Committee for Democracy, which promoted the American war effort but was considered by the military gumshoes to be a Communist-influenced group. In one letter to Seeger, Ohta said she suspected that the combination of Seeger’s past work with the Almanac Singers, a group of lefty folk singers who sang mostly pro-labor songs, and his relationship with her would prevent him from being deployed overseas. She wrote, “Not that I mind that…from the danger point of view…But what good is your going through all this training and having the government spend so much money on you…if they don’t allow you to use it.” Seeger, several days later, wrote to his grandmother: “It is possible that I am being held here because of my former connections with the Almanac Singers and because of my engagement to a Japanese-American, but I doubt it. I have never tried to hide either fact.”

Early in the investigation, an officer at Keesler Field interviewed Seeger, who noted that he was puzzled that he had not been deployed as an aviation mechanic, given that he had completed his training. Seeger pointed out that he played the five-string banjo well and requested that he be assigned to the Special Services Department, which provided entertainment for the troops. Seeger was asked about Ohta, and he informed the officer that her father was a Japanese refugee who had come to the United States because he disagreed with the militarists of Japan. Seeger said Ohta’s father had been given the choice of being executed in Japan or leaving the country. He told the officer that the Japanese American Committee for Democracy sought to demonstrate that Japanese Americans were loyal citizens and that its sponsors included Albert Einstein and author Pearl Buck.

Seeger was not informed that he was under investigation.

After the interview, the officer wrote in a memo that he believed Seeger had been “truthful in all answers…and that he made no attempt to withhold anything.” The officer added, “From all indications, Subject has no idea that anything he has done or any associations he might have had in the past or might have at the present time would be cause to hold him on this field or keep him under surveillance at any time.” In a diary entry Seeger wrote later that year, he said he thought the questioning was prompted because someone had seen the return address on the letters that Ohta had sent him: “I was very frank with them, spontaneously volunteering all I thought they would want. I thought I had satisfied them.” Seeger did not initially realize the military snoops were reading his mail and thoroughly investigating him. But months after this interview, he would suspect that his mail was being opened. He then came to the conclusion that his deployment was being blocked: “I hoped it was because of Toshi, but was afraid that it was because of my work as an Almanac Singer.”

As part of the probe prompted by Seeger’s protest letter, a military intelligence agent visited the grade school in Litchfield, Connecticut, that Seeger had attended—and found the available records did not cover the period when Seeger had been there. (And, he wrote in a report, “it is doubtful that the information obtained would be of any value.”) This agent also went to Seeger’s high school in Avon, Connecticut. (A member of the faculty said Seeger “possessed unusual literary talents” and was intelligent and “completely honest and reliable.”) The report based on this interview noted that Seeger, after leaving high school, “appeared to have assumed a ‘Bohemian’ attitude in dress and appearance” and that this faculty member had concluded that Seeger had “developed a somewhat radical outlook on life” but was in no way “dangerous.”

Another agent went to Harvard University, where Seeger had studied for a year and a half before withdrawing due to financial reasons, and he managed to review Seeger’s academic records (“Grades in the first year were fair”) and gain access to the membership list of the Harvard Student Union, of which Seeger had been the secretary. This agent spoke to faculty members and acquaintances of Seeger at Harvard, but they only remembered him slightly.

An agent in Detroit, Michigan, interviewed the director of student activities at Wayne State University about concerts there that had featured the Almanac Singers. (The interviewee had nothing to say about Seeger.) This agent also questioned the owner of a record store where the Almanac Singers had stored their instruments when they were in Detroit. A pal of Seeger’s told another agent that, after studying at Harvard, Seeger had traveled around the country performing and collecting folk music, and that he had attended “Communist meetings.” This friends said Seeger had been interested in the Communist Party because, as the interview report put it, “under their program the artist had an opportunity to produce his works without worry of starving to death, as they were subsidized by the government for such work.”

As part of the Seeger probe, military intelligence did investigate Ohta. It also probed Charles Seeger, Pete’s father and a noted musicologist. An agent interviewed the father “under pretext”—meaning the agent cooked up a phony reason for the interview—according to a report he later filed. Charles told the agent that his son had “bummed around” the country, playing the banjo and singing, before being drafted into the Army, and was “very much interested in the common people.” Pete Seeger, this agent’s report noted, “was a close friend and associate of ‘Leadbetter,’ also known as ‘Leadbelly,’ a negro murderer who escaped from prison a few years ago.” (Lead Belly, whose real name was Huddie Ledbetter, did go to jail for killing a relative but was pardoned in 1925 after serving the minimum sentence. He went on to become a renowned folk singer.) Seeger’s father pointed out that his son was frustrated that he had not yet been transferred to active duty and combat. He said his son was not a radical but possessed a liberal point of view.

On May Day in 1943, a military intelligence agent in New York City named Harwood Ryan interviewed folk singer Woody Guthrie as part of the Seeger investigation. Guthrie, who had been a member of the Almanac Singers, recounted that he had met Seeger in the summer of 1941 when both men had joined the group. Most of the act’s engagements, Guthrie said, had been in union halls, and Seeger had been the best musician in the group and written most of the lyrics for their original songs. Guthrie told Ryan that the Almanac Singers had slept on freight trains, under bridges, and in churches while touring. According to the report Ryan filed, Guthrie gave the following description of Seeger:

[He] had been greatly interested in American folklore and had always been interested in people and what they were doing. [Seeger] had a great deal of energy and was brilliant, but he was hard to understand. Guthrie attributed this to the fact that [Seeger] always wanted to see things done in a more efficient and better way than they were being done. In addition, [Seeger] loved good organization and was always active in trying to make group endeavors work more smoothly. Guthrie would not name any of the groups, but said he referred to many kinds of outings or meetings in which people assembled at large gatherings.

Ryan asked Guthrie about Seeger’s political views, and Guthrie responded:

[Seeger] was progressive in his outlook and had liberal views, maintaining that men had the right to organize and bargain collectively. In addition, [Seeger] was very much in favor of labor unions and most of the Almanacs’ bookings were by such unions. According to Guthrie, [Seeger’s] present politics are National Unity. Guthrie emphasized that [Seeger] is not an overthrower, but he is out to win the war. What [Seeger] wants personally, is to do Hitler the most damage possible. Guthrie said he had just received a letter stating that [Seeger] was extremely anxious to be sent on active service and that he could not understand why he was being held inactive in an unassigned group.

Guthrie told Ryan that Seeger could be trusted and that the Army should put his talents and strong mind to good use.

Ryan, though, was suspicious of Guthrie and thought he was being cagey about Seeger’s political beliefs. In his report, he noted that in Guthrie’s apartment he had spotted a large guitar that bore an inscription: “This machine kills Fascists.” Ryan added that he believed “this bears out the belief that the Almanac Players were active singing Communist songs and spreading propaganda.” He reported that he thought Guthrie had been “truthful as far as he went, but that he knew a great deal more about [Seeger’s] politics and activities than he admitted.”

Throughout 1943, the results of the military’s probe were compiled in reports on Seeger. One memo reported that Seeger’s “supervisors at Harvard University considered that Subject had radical ideas…and one of the supervisors thought that the Subject had a leaning towards Communism.” It noted that a “reliable source” had said one of Seeger’s “acquaintances” was a “self-confessed Communist, ardent in his love for the Communistic teachings of Russia,” and one “acquaintance”—maybe the same one—said Seeger was “in sympathy with the Communist cause.” The author of the report concluded that Seeger “will be further influenced along questionable lines by his new wife, the former Toshi Ohta, who is half-Japanese…Correspondence between the two indicated that both…were deeply interested in political trends, particularly anti-Fascist, and that she was a member of several Communist infiltrated organizations. Their marriage will quite possibly fuse and strengthen their individual radical tendencies.” The report concluded that Seeger was “an idealist whose devotion to radical ideologies is such as to make his loyalty to the United States under all circumstances questionable.” Seeger, this memo claimed, was “potentially subversive.” The document was sent to J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI.

Another military intelligence report concluded that Seeger’s “Communistic sypmpathies.…and his numerous Communist and otherwise undesirable friends” rendered him “unfit for a position of trust or reliability.” A third report said Seeger is “intensely loyal at this time. He is eager to join the battle actively against Fascism, and is applying himself to improve his military and technical knowledge to be of greatest service.” But it added that if the Communist Party line shifted against the war, Seeger could be susceptible to “potential subversion.” This report also focused on his love for Toshi Ohta: “While this relationship appears on a high plane, this Officer believes it to be unorthodox and one which might lead to divided loyalty in the event this country’s treatment of the Japanese were not in accord with the views of himself or the woman he expects to marry.” It went on to point out that “as an entertainer, his songs have been colored subtly toward idealistic classlessness.” And this memo concluded, “Despite [Seeger’s] intelligence and desire to apply himself to the destruction of the enemy, this officer believes that enemy to be Fascism and not necessarily any enemy of the United States.” That is, Seeger was more loyal to an abstraction than his country. The recommendation: that he remain under surveillance as a “potentially subversive” person.

The Seeger investigation apparently petered out after he was transferred to an airfield in Texas. But Seeger was not sent abroad as an aviation mechanic. Instead, he did become part of the Army division responsible for entertaining the troops. In the summer of 1944, he shipped off to the Pacific Theater, and he sang his way through the rest of the war.

After the war, Seeger remained an FBI target. It was a time of communist hunting. Confidential informants had fingered Seeger as a party member or sympathizer, and throughout the 1950s the FBI generated hundreds of reports on Seeger. The bureau closely tracked his musical performances and his appearances at political events. It monitored his associations with groups and persons suspected of being linked to or controlled by the Communist Party. FBI agents called his booking agency and pretended to be people who wanted to arrange a Seeger performance in order to collect information on his travels within the United States and overseas. The burgeoning folk music world overlapped with the progressive movement (which the bureau saw as riddled with and dominated by commies) and Seeger was at the nexus.

In the early 1950s, Seeger was a member of the Weavers folk group, as it became a national act with a string of hits. The group sold an estimated 4 million singles and albums. But as the Weaver reached this height, Seeger became the target of the blacklist banning entertainers suspected of Communist Party ties. A Senate committee investigated the Weavers. The demand for Weavers shows diminished. In 1953, two FBI agents working in the Security Informant Program tried to interview Seeger after he dropped one of his children at school near his home in upstate New York. “I think I had just better not say anything,” he told them.

In 1955, Seeger was called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Asked if he was a communist, Seeger defiantly replied, “I am not going to answer any questions as to my associations, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs or how I voted in any election or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked.” He did not plead the Fifth Amendment. He took a stand, telling the committee, “I would be very glad to tell you my life, if you want to hear of it.” He added, “If you want to question me about any songs…I will be glad to tell what songs I have ever sung, because singing is my business.” Seeger told the committee, “I have sung for Americans of every political persuasion…I have sung in hobo jungles, and I have sung for the Rockefellers.”

The congressmen running the commie-hunting committee were not pleased. In 1957, Seeger was cited for contempt of Congress for not answering the questions about his political associations. Four years later, after much legal wrangling, he was found guilty after a three-day trial. Seeger was sentenced to a year in prison. He remained free on bail, and a year later, the conviction was overturned when a federal appeals court determined the original indictment had been defective. After that, the Justice Department dropped the case.

Seeger’s FBI files indicate the FBI actively monitored the contempt case against Seeger. Its agents stayed in contact with the prosecutors handling the case, as the bureau kept gathering information on Seeger’s connections to progressive organizations—civil liberties and civil rights outfits, peace groups, pro-labor entities, and the like—that it deemed subversive. It closely watched his use of his passport.

After the contempt case concluded, the FBI remained on the Seeger beat. When the folk singer traveled abroad, according to a 1963 FBI note from Hoover to the State Department, the bureau notified the CIA and asked for any information it might obtain on Seeger overseas. At one point, when Seeger played a series of concerts in Hawaii in 1963, the FBI collected information on the shows, noting that an audience member from an “avowedly anti-Communist organization” had reported to the bureau that Seeger had sung a song that was “low keyed propaganda to the effect that America is a land of conformity” and also played a song from Japan about nuclear bombs. This source noted that “Where Have All The Flowers Gone?” was inspired by a passage from a Soviet writer. In 1966, a FBI memo recorded the fact—obtained form a “reliable” source—that Seeger had registered for a Russian-language course. The bureau kept in touch with the police force and the postmaster of Beacon, New York, where Seeger and his wife, Toshi, lived, to keep a close eye on his comings and goings.

FBI surveillance of Seeger continued into the early 1970s. A 1971 FBI report listing evidence of his “CP Sympathy” noted that Seeger had entertained at a benefit concert for three soldiers who had refused to serve in Vietnam because they believed the war there was illegal, immoral, and unjust. Also, it pointed out that he had raised money at a Los Angeles concert for a group called Southern Californians to Abolish the House Committee for Un-American Activities. A 1972 FBI memo reported that Seeger “has manifested a revolutionary ideology.” The message: He still needed watching.

By that point, Seeger had broken free from the black list, appearing on network television five years earlier on the popular Smothers Brothers’ variety show. And he had become a prominent environmental crusader, building the Clearwater, a 106-foot sailing ship that cruised the Hudson River to promote efforts to clean up that major waterway. In the decades to come, Seeger kept on singing and organizing. While his FBI file gathered dust, he received numerous honors. He was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1972. President Bill Clinton in 1994 awarded him the National Medal of Arts. Seeger entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996, as an early influencer. He won Grammy awards. He performed on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during an inaugural concert for President Barack Obama.

Seeger was 94 years old when he died. His wide-ranging impact on popular culture, music, and politics had survived all the efforts—behind closed doors and in the public—to brand him a subversive and an enemy of freedom. This was seven decades after he first became a target of government snoops merely because he was upset about a racist and unconstitutional idea and, as a private citizen, wrote a letter about it.