<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-69897520/stock-photo-the-front-of-the-us-supreme-court-in-washington-dc.html?src=csl_recent_image-1">Gary Blakeley</a>/Shutterstock

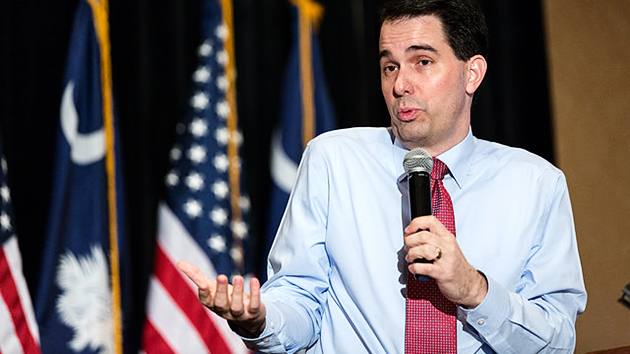

It’s the campaign scandal that just won’t die. For three years, prosecutors in Wisconsin tried to investigate what they believed was illegal campaign coordination between Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and conservative outside groups. The investigation has become a political flash point in the state: Walker and conservatives claim it is a witch hunt led by liberal prosecutors, while liberals believe it is about the power of dark money in Wisconsin politics.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court dismissed the case, but on Friday, the case moved to the national stage when prosecutors signaled their intention to take it to the US Supreme Court. And the focus is now set to shift from the actions of Walker and his allies to potential ethical violations by the Wisconsin Supreme Court justices themselves.

This summer, the Wisconsin Supreme Court took up the question of whether to stop the investigation into alleged coordination between Walker’s 2012 recall campaign and conservative outside groups that receive unlimited donations from undisclosed donors. The problem was that the election campaigns of two justices on the state’s top court had benefited significantly from spending by those same groups accused of illegal coordination with Walker. The special prosecutor overseeing the investigation, along with legal ethicists, asked the two justices with conflicts of interest to recuse themselves. But no justices stepped aside.

The court shut down the investigation by ruling that the type of coordination at issue was actually legal—that campaigns and outside dark-money groups can coordinate as long as they don’t produce ads that explicitly say “vote for” or “vote against” a candidate. And that was supposed to be the end of the story.

Then, in August, the special prosecutor, Francis Schmitz, asked the state Supreme Court to consider reopening the investigation. The request was viewed as a sign that Schmitz was considering an appeal to the US Supreme Court. Not only did the court say no; it went further, issuing an opinion earlier this month that removed Schmitz from the case, making it harder for him to appeal to the US Supreme Court. (To do this, the court found that Schmitz was improperly appointed to lead the investigation. This was a reversal from the summer, when the court allowed Schmitz’s appointment.)

Schmitz, a Republican, wants to see the case go to the nation’s highest court. “If I have the resources, [I] intend to pursue an appeal before the US Supreme Court,” Schmitz announced after the state’s top court took him off the case. “The miscalculation I made in this investigation was underestimating the power and influence special-interest groups have in Wisconsin politics.”

But Schmitz’s caveat—”if I have the resources”—is an important one. By taking Schmitz off the case, the justices assured that any appeal Schmitz files won’t be paid for by the state. And appealing to the US Supreme Court, much less arguing a case before it, is an expensive endeavor to take on without pay. Just the initial petition to the court can cost upward of $25,000.

Although Schmitz was removed from the case, cutting him off from resources for an appeal, the court gave the other five prosecutors involved in the case the ability to intervene. On Friday, three Democratic district attorneys who had worked with Schmitz on the investigation chose to intervene in the case—signaling they want to go to the US Supreme Court.

There are two potential issues that the district attorneys could appeal to the Supreme Court: a challenge on the merits of the state court’s campaign finance ruling, and an ethical challenge to the failure of the justices to recuse themselves. It’s the second question that experts believe makes for the stronger case.

“I would not want to bring any campaign finance case to this Supreme Court,” says Rick Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California-Irvine School of Law, nodding to the conservative bent of the court on this issue. But the recusal question, he says, “has a decent chance.” And that’s where court watchers believe the case will indeed focus.

In 2009, the Supreme Court ruled in Caperton v. Massey that a judge deprived the plaintiff in the case of due process rights by failing to recuse himself despite a significant conflict of interest. The 5-4 decision was written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, who joined the court’s four liberal justices on the issue. “I do think there is a plausible Caperton claim to be brought,” says Hasen. On the one hand, Caperton set a high bar and has been applied only to egregious cases; on the other, several justices on the Wisconsin Supreme Court arguably hold their seats as a result of spending by the same groups who were being investigated.

The Supreme Court takes only a fraction of the appeals that come its way. But if it does consider a Caperton challenge to the situation in Wisconsin, it could not just determine whether the Wisconsin Supreme Court crossed the line when it came to conflicts of interest, but could help set ethical standards across the country in an era when judicial elections are increasingly fought with millions of dollars in outside spending.