On any given night, 1 in 200 San Franciscans sleep on the street. Among the nation’s large urban areas, the city has the highest per capita rate of unsheltered homeless people—people who live outside, in cars, or in abandoned buildings, as opposed to in shelters or transitional housing. Over the past decade, as the city has experienced a tech boom and sky-high housing prices, the number of homeless people living in the open has increased 64 percent, to nearly 4,400 people, according to the most current (though controversial) count.

San Francisco’s growing homeless population

Homelessness isn’t unique to San Francisco, of course: All told, there are nearly 600,000 homeless individuals in the United States. That number has dropped slightly over the years, from 647,000 in 2007 to 575,000 last year. But in several big cities—such as New York, Seattle, Miami, San Francisco, and Washington, DC—the number of homeless people has increased over the same period.

Homelessness in 15 largest US cities, 2015

How’d we get here?

Given San Francisco’s increasingly visible, stubbornly high homelessness rate, it’s easy to forget that homelessness is a relatively recent phenomenon—one that housing experts agree began in earnest in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

To get a better sense of the historical and ongoing causes of homelessness, I spoke with researchers from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the National Low Income Housing Coalition, and the California Housing Partnership Corporation. They pointed to a sequence of policies in the ’80s and ’90s that cut housing and social services for America’s poorest residents, eliminating the safety nets that once kept many people from landing on the streets.

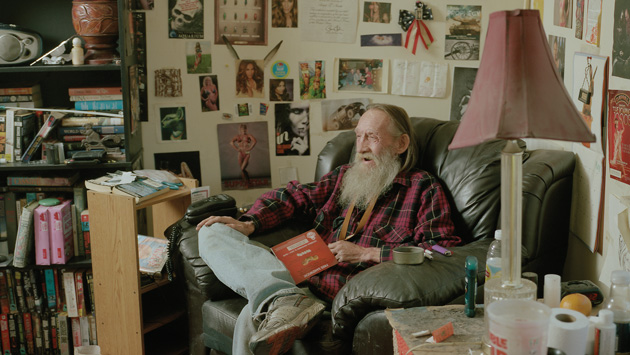

The researchers at all three organizations pointed out a paradox: While homelessness is experienced and witnessed at a local level, the underlying causes are systematic, long term, and largely the results of decisions made at the federal level. These root causes have been well established for decades, says Stacey Murphy, the research director of the California Housing Partnership Corporation: the decline in wages, cuts to welfare and affordable housing, and the lack of mental health services. “It’s the same four things. It’s mystifying to me,” she says. “When people stop thinking about it as one person and think about policy—when you ask, as a nation, why so many people live on the streets and how we can not provide a basic level of services for those people—it raises profound questions about our society.”

Here are some factors that have driven San Francisco’s—and the nation’s—homelessness problem for the past four decades.

Affordable housing cuts

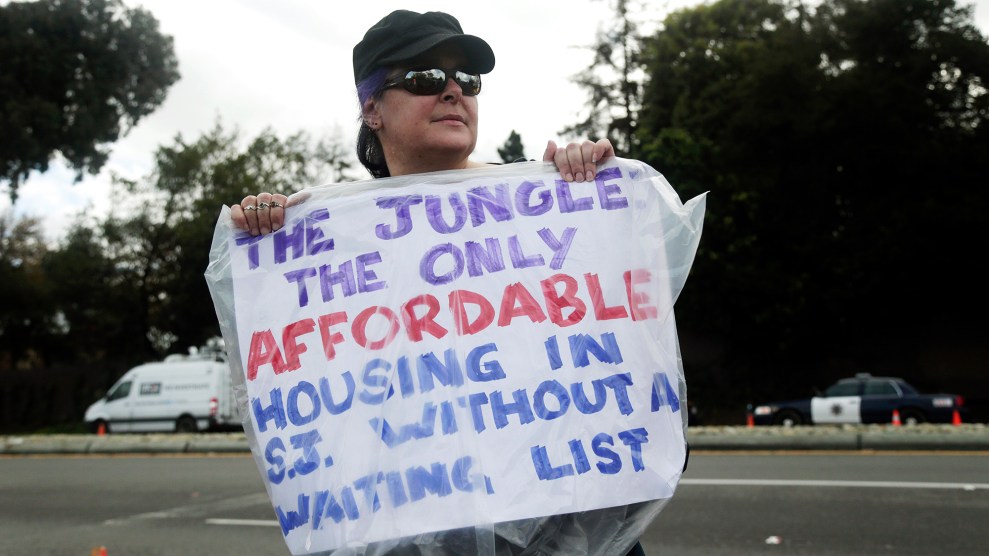

Reaganomics brought prosperity for some, but its small-government policies led to massive funding cuts to federal affordable housing programs and social services. “When we look at the affordable housing crisis today, there’s a direct line back to really severe cuts that were made to critical affordable housing programs under the Reagan administration,” says Diane Yentel, the president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition. She points out that, unlike other federal safety nets like Social Security and Medicare, affordable housing isn’t automatic even if you qualify for it. “When public housing agencies open up a waiting list, you’ll see long lines of people waiting just to add their name to the waiting list—and they’re waiting literally decades,” she says. Today, there are just three affordable and available housing units for every 10 extremely low-income families, according to the NLIHC.

(The spike in 2009 was the effect of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act stimulus package, which included one-time funding for housing.)

Sagging incomes, soaring rents

As the chart below shows, family income roughly doubled across all income groups in the two decades after World War II. But starting in the mid-’70s, income disparities widened: Families in the top bracket continued to see their incomes rise while the incomes of middle-class and low-income families stagnated.

While income has flatlined for many Americans, rents are rising—and fast—in many cities. This is partly a matter of supply and demand: In cities like San Francisco, the supply of housing units has not kept up with population growth.

The gap between income and rent is particularly extreme among San Francisco’s low-income residents. Over the past decade, the monthly income of a low-income San Francisco household (one that makes 30 percent of the median, which is currently $107,700 annually) has increased by 14 percent, not adjusting for inflation. Over the same period, the median rent for a modest two-bedroom apartment rose 38 percent. In order to make that rent without spending more than 30 percent of their annual income, a person would need to make $44 an hour, or more than $91,000 per year.

Welfare cuts

Until 1996, poor families could count on federal welfare benefits, says Murphy. “It didn’t say you would get a lot, but if you were poor and met requirements, the federal government footed the bill. Welfare reform changed that.” The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act signed by President Bill Clinton gave states the power to decide who would receive federal assistance. States imposed stricter eligibility rules, and all families were limited to a total of five years on welfare.

In 1995, three of four families with children in poverty received welfare benefits. By 2014, that number had dropped to one in four. Since welfare benefits are largely spent on rent, the reduction in benefits means fewer families in poverty are able to afford a home. “If you’re not receiving cash assistance at all, [welfare] is not helping you pay for housing,” says Liz Schott, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Benefits don’t go as far

As the number of poor families on welfare has declined, so has the value of those benefits. In 1980, a family of three living in the Bay Area received a maximum benefit of $473 a month, or $1,361 in 2015 dollars. In 2015, the maximum such a family could receive was $704, an effective cut of nearly 50 percent. “Very few people are on assistance. but those who are say they can’t meet their basic needs like housing by just relying on assistance,” says Ife Floyd, a policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “It’s the same story across the country.”