By now, you know the contours of the latest OMG moment in Journalism vs. Billionaires. Peter Thiel—the founder of PayPal, pledged Trump delegate, and occasional skeptic of women’s suffrage—bankrolled a lawsuit by wrestler Hulk Hogan that pushed Gawker Media into filing for bankruptcy protection last week. Thiel said he’s had it in for Gawker ever since 2007, when the site ran a (fairly flattering) article headlined “Peter Thiel Is Totally Gay, People”, and that he sought out “victims” of its reporting with a goal of “specific deterrence” against media companies.

Now, deterrence can mean many things, but for those—like Thiel, and the two of us—who came of age in the ’80s, it carries a specific resonance. Deterrence, at the height of the Cold War, meant building a massive arsenal of nuclear weapons to make sure the other side never used theirs.

In truth, the Thiel-Gawker fight is more like US vs. Grenada than US vs. USSR. Gawker Media is not an insignificant player, but it’s a $250-million company at best, in an industry with razor-thin margins. Thiel’s personal fortune is estimated at $2.7 billion, and—as evidenced by the outpouring of Silicon Valley sympathy for his crusade—he carries quite a bit of weight among his fellow tech titans.

Here’s the thing: Most people think of “the media” as very powerful. And that may be true, if you define “media” as everything from Netflix and HBO to Univision and Disney. But “journalism” is a very small subsegment of that big “media industry”—and journalism is more vulnerable than it’s ever been.

The threats come in part from the balance sheet: newsrooms don’t make money. (Gawker’s $6.7 million or so in profit is derived in good part from links to Amazon shopping pages.) But they also come from powerful people to whom the cost of company-bankrupting litigation is pocket change.

When these men, and they are mostly men, are willing to go nuclear, there’s very little in the institutions of democracy that can stop them. (See also: The GOP primary. More on that in a second.)

This is not about whether Gawker should have published a pro wrestler’s sex tape. It’s not even about whether they should have been made to defend that decision in court, and if found to have gone beyond bounds, paid a price. (Gawker itself offered what were apparently substantial settlements during the litigation.) It’s about whether people with massive resources get to decide what media are allowed to publish—rather than, say, the courts, or Congress, or you. Thiel, a renowned libertarian, evidently believes that private individuals should exercise a power the founders considered so significant the they prohibited government from using it in the very first amendment to the Constitution.

It may seem odd that this push to restrict speech would emanate from the tech industry—an industry that has embraced the idea that information should be free. Then again, maybe not. As Gawker founder Nick Denton pointed out in an open letter to Thiel,

For Silicon Valley, the media spotlight is a relatively recent phenomenon. Most executives and venture capitalists are accustomed to dealing with acquiescent trade journalists and a dazzled mainstream media, who will typically play along with embargoes, join in enthusiasm for new products, and hew to the authorized version of a story. They do not have the sophistication, and the thicker skins, of public figures in older power centers such as New York, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C.

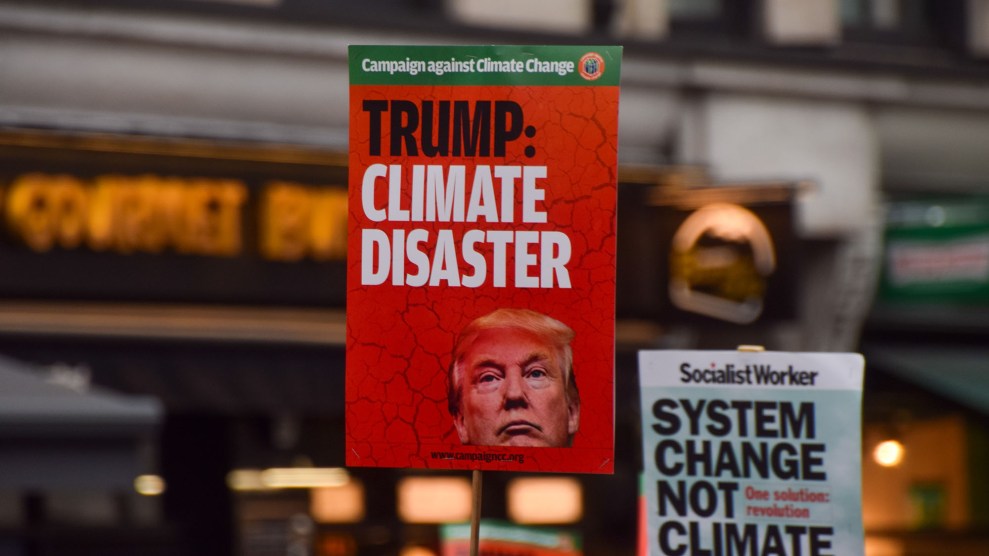

But it’s not just tech. A few years ago, Donald Trump sued Timothy O’Brien, a reporter then with the New York Times and now with Bloomberg, for raising questions about his net worth. Being Trump, he didn’t hold back about what he was after: “I did it to make his life miserable.”

Trump also wants to change libel laws “so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money.” (Never mind that libel law is already designed to do just that—punish those who publish false and defamatory information.)

The list goes on. Sheldon Adelson, the casino mogul, sued John L. Smith, a columnist at the Las Vegas Review-Journal, driving him into bankruptcy at a time when his young daughter struggled with brain cancer. (One of the few things Smith was able to hang on to was his job at the paper—until Adelson bought the Review-Journal late last year, and management decreed that Smith could no longer cover Adelson.)

And then there’s Frank VanderSloot, the dark-money billionaire who spent nearly three years going after Mother Jones for covering his anti-LGBT rights activism, forcing us to spend a huge amount of time and money to defend ourselves. (More about the details of that case here.) And just in case anyone missed the point, after being handed a resounding loss by a local Idaho judge, VanderSloot announced that he was pledging $1 million to a fund to underwrite people who wanted to sue Mother Jones, or other elements of the “liberal media.” We have been warned.

For the likes of VanderSloot, Adelson, Thiel, and Trump, the courts have become an avenue not so much for vindication, but for exacting a price. Make a news organization spend enough time and cash ($600,000 in our case, in addition to the $2 million our insurance company had to pony up), and you’re going to have an effect—on that newsroom, and many others. People will ask themselves, in private if not in public: Do we really need to publish this fact that we know is true? Or should we hold back, knowing that being correct doesn’t protect us from being dragged into court?

As Talking Points Memo’s Josh Marshall wrote apropos the Thiel revelations,

If the extremely wealthy, under a veil [of] secrecy, can destroy publications they want to silence, that’s a far bigger threat to freedom of the press than most of the things we commonly worry about on that front. If this is the new weapon in the arsenal of the super rich, few publications will have the resources or the death wish to scrutinize them closely.

At Mother Jones, we have been thinking about that a lot. We work on multiple stories at any given time that could piss someone very wealthy off enough to prompt a lawsuit. We have insurance, but as we learned, there is a lot that insurance doesn’t cover. (And there are other costs. As one of our colleagues in nonprofit news, the founder of the tiny Southern Investigative Reporting Foundation, has noted: “It used to be a badge of honor when a company sent you a letter. I never had to give a crap. Now my lawyers say we have to report that to your insurance carrier. Then your insurance carrier says we’re dropping you. Or we have to hike your premium by 400 percent.”)

So there are choices we as journalists have to make, every day. But there are also choices for you. If you believe journalists need to cover the facts as they see them, and not as billionaires would like them for them to be seen, there are two things you can do.

One, add your voice to those pushing for a federal law banning “strategic lawsuits against public participation”—SLAPP suits. Those are lawsuits that a court finds are simply intended to constrain speech (sometimes involving media, sometimes others—say, environmental activists facing a defamation suit from the polluter they’ve targeted). A number of states already have such laws, but many don’t—including Idaho, where VanderSloot sued Mother Jones. That’s why we weren’t able to get the litigation dismissed at the outset, as we might have in California, and it’s why we can’t go after him for our legal costs.

That’s right: The $600,000-plus we spent out of pocket is for us to deal with. And we’ve gotten some amazing help: the First Look Media Press Freedom Litigation Fund (launched by another tech billionaire, Pierre Omidyar) gave us a $75,000 grant, and readers have pitched in nearly $350,000. But we are still $175,000 in the hole. And as you know, we’re a nonprofit—the vast majority of our revenue comes from our readers, and every penny we bring in goes right back into the journalism. We don’t have stockholders or a corporate parent who can pick up the tab.

So yes, this article ends with a pitch about the other thing you can do. With just a couple of weeks to go until the end of our fiscal year, we’re pretty much out of options for covering that $175,000 in legal costs. Will you help us retire the bills, so we can go into whatever fight is next with a clean slate? If so, please consider becoming a monthly sustainer, by committing to a regular tax-deductible contribution at the level that’s right for you. (If you can afford $5 or more each month, you also get a free subscription to our award-winning, and freshly redesigned, print magazine). Have commitment issues? No problem: Please pitch in with a one-time gift.

Knowing that readers have our back will make the next litigious billionaire think a little harder about coming after us. MoJo‘s entire budget may look like a rounding error to a tycoon—but what we have that they don’t is millions of readers like you.