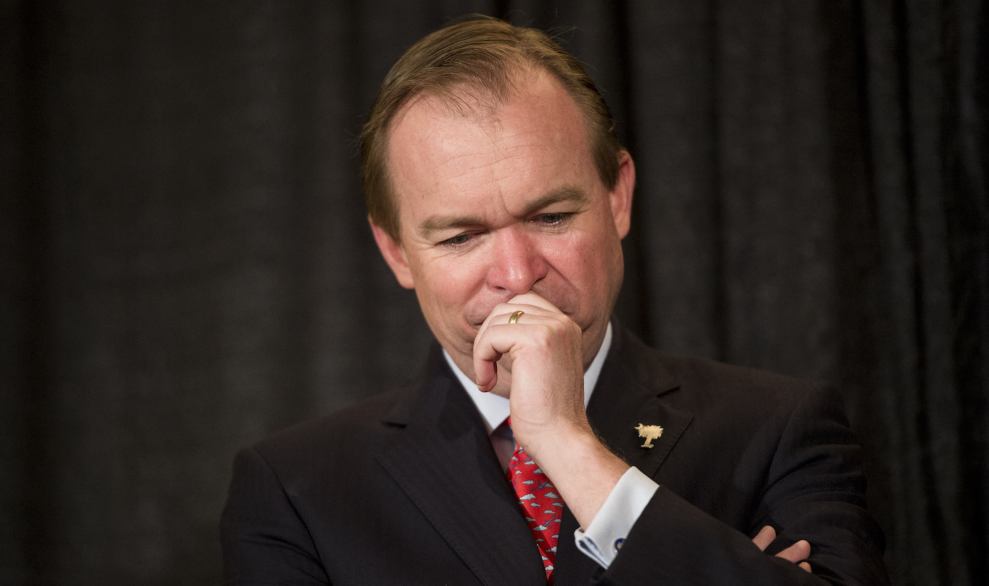

Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Newscom via ZUMA

Mick Mulvaney, the ultra-conservative South Carolina congressman whom Donald Trump has tapped to be his budget director, has questioned whether the federal government should spend any money on scientific research.

If confirmed by the Senate to lead the Office of Management and Budget, Mulvaney, a deficit hawk who recently spoke before a chapter of the right-wing-fringe John Birch Society, would be in charge of crafting Trump’s budget and overseeing the functioning of federal agencies. One thing he seems to believe the budget and the agencies should not be funding is research into diseases like the Zika virus.

Two weeks before Congress finally passed more than $1 billion to fight the spread of Zika and its effects, Mulvaney questioned whether the government should fund any scientific research. “[D]o we need government-funded research at all,” he wrote in a Facebook post on September 9 unearthed by the Democratic opposition research group American Bridge. Mulvaney appears to have deleted his Facebook page since then.

In the post, he justified his position on government-funded research by questioning the scientific consensus that Zika causes the birth defect microcephaly. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) concluded in April that the Zika virus causes microcephaly and other defects. But Mulvaney wrote:

And before you inundate me with pictures of children with birth defects, consider this:

Brazil’s microcephaly epidemic continues to pose a mystery — if Zika is the culprit, why are there no similar epidemics in countries also hit hard by the virus? In Brazil, the microcephaly rate soared with more than 1,500 confirmed cases. But in Colombia, a recent study of nearly 12,000 pregnant women infected with Zika found zero microcephaly cases. If Zika is to blame for microcephaly, where are the missing cases? According to a new report from the New England Complex Systems Institute (NECSI), the number of missing cases in Colombia and elsewhere raises serious questions about the assumed connection between Zika and microcephaly.

According to the New York Times, the relatively low rate of microcephaly in Colombia has indeed puzzled some researchers, who point to the fact that many women likely delayed pregnancy or had abortions when testing revealed the birth defect. But that doesn’t change the scientific consensus linking Zika to microcephaly.

Here’s the full post from Mulvaney: