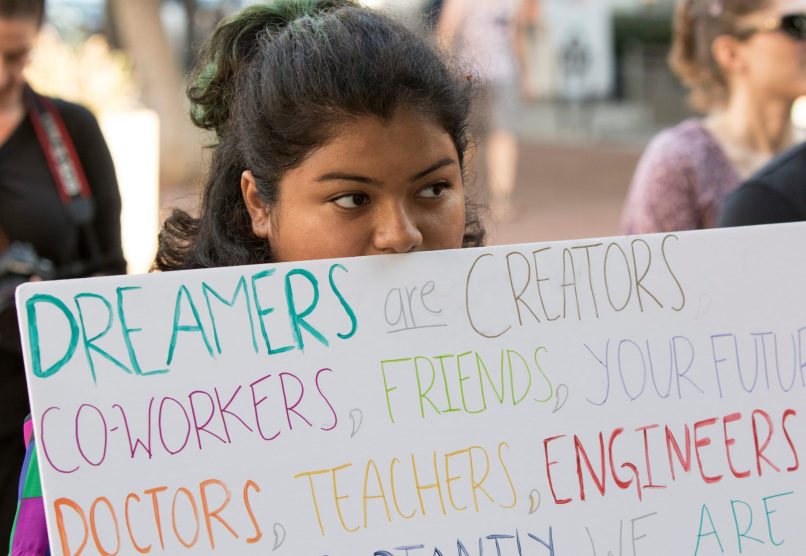

New Yorkers protest Trump's end to DACAZUMA

On a recent Saturday, as picnickers and sun worshippers relaxed in San Francisco’s Dolores Park, 200 people spent the afternoon across the street in the cafeteria of Mission High School, trying to extend their status as recipients of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). The free legal consultation was the last city-sponsored workshop before the October 5 deadline for DACA renewal applications to be received by the Department of Homeland Security.

Across the country, nonprofit organizations, legal groups, and school districts have been holding similar events almost every day since Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ September 5 announcement that the Trump administration will end DACA. The program, created in 2012 by President Barack Obama, granted temporary work permits to people brought to the country illegally as children and protected them from deportation. Under the Trump administration’s new policy, no new DACA work permits will be issued. However, current recipients whose work permits expire before March 5, 2018 may submit applications for renewal before October 5. US Citizenship and Immigration Services told Vox that 111,565 of the roughly 154,000 eligible to apply had sent in applications by Wednesday.

“This is really an emergency workshop where we’re making sure that every DACA holder who’s eligible to apply doesn’t have to worry about fees, legal assistance, or even their passport photo,” said Adrienne Pon, executive director of the city’s Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs. More than 100 people had RSVP’d for the event, she said, but dozens more showed up. Through an emergency grant from the city, her office was covering the $495-plus filing fee for everyone who attended.

Workshop attendees came from across the Bay Area—and California—for the “one-stop-shop” event. Many lined up more than an hour before the 1 p.m. start time, having traveled from Pittsburg, Gilroy, San Mateo, Hayward, and even Los Angeles. “This was the only event I heard of that could provide the financial assistance I needed,” said Carl, a 25-year-old who had taken a seven-hour bus ride from LA the night before. (He asked that his last name not be used.)

The atmosphere in the high school was calm and friendly despite the serious nature of the event. Chenyu Wang, a volunteer immigration attorney for Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach, stood at the entrance of the cafeteria, where lawyers and volunteers had set up tables to provide advice and assist with paperwork. The end of the Obama-era program, he said, “puts a lot of kids back in the position they were before they had DACA, which meant not being able to have a good job, not being able to get many government services. They have to essentially go back to being second-class citizens and even worse.”

It’s already too late for many DACA recipients. “Unfortunately, we’ve been receiving a lot more cases of people coming in who are ineligible, who are outside the deadlines to submit their applications,” said Paulina Moreno, director of programs at the Services, Immigrant Rights and Education Network (SIREN) in San Jose, California. As the renewal deadline looms, the center has been scrambling to provide legal advice to as many people as possible at daily workshops around Santa Clara County. Legal fees have been waived, and the group has secured funds to cover the renewal fee.

One morning last week, 28-year-old Pedro Quintana dropped into SIREN’s offices for a free consultation. He was aware that his DACA work permit expires in May 2018, making him ineligible for the renewal deadline. Quintana has seven months to make a plan before he’s at risk of being deported to Mexico, a country he hasn’t seen in almost 20 years.

Quintana came to the United States from Michoacán, Mexico, with his brother and mother when he was nine. “I keep telling my mom if we hadn’t left I’m pretty sure I’d either be a criminal or I would be dead. Because there’s only two options,” Quintana said. Instead of staying in the shadows, Quintana felt “rebellious,” succeeding in school, graduating college with a degree in kinesiology, and starting a personal fitness company.

Still, he was scared of the risks of being undocumented. Like the time he got a scholarship to fly to Washington, D.C. Or every time a police car drove by. He was terrified of being put into deportation proceedings. He didn’t know the relief of being lawfully present in the United States until he was 25, when he obtained a work permit through DACA. That made him less afraid, though he said that changed after the 2016 election.

“The best way to could describe it is like a crab. You’re always kind of hiding in your shell and you’re always kind of going trying to be under a rock, always hiding.” Quintana said. “You always want to be the ideal civilian because if you get stopped you don’t have any ID or registration of any type.”

In San Francisco, 22-year old Mayra Guizar pulled her three-year-old son from the carrier on her boyfriend’s back and bounced him on her hip as she talked about life before DACA. She had worked in a warehouse where the conditions were “horrible,” and the supervisor verbally abused her and the other employees, calling them “illegals” and “wetbacks.” Before that, Guizar was a waitress and was paid under the table. Her boss harassed her, she recalled, but being young and undocumented, she felt that she couldn’t speak out.

In 2012, Guizar received DACA. “It was a relief because I was able to get a real job, you know?” she said. She is now a caseworker at a nonprofit health center in Hayward. She said that the decision to end DACA means she may no longer be able to help her community. It also could mean that she will have to return to Mexico: “It would be terrible if I had to leave. I was brought here when I was only two, so not knowing anybody, going to a country where there’s a lot of terrorism, it’s really scary.”

Guizar’s DACA permit expired in May. She had submitted her renewal application before the policy change, but she said it was rejected because she sent the fee in two money orders instead of one. Though the lawyer she spoke with at the workshop told her there’s no guarantee that her renewal will be successfully processed, Guizar remained optimistic.

There are large immigrant communities throughout the Bay Area, but most of the DACA renewal workshops have been in bigger cities like San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland.

“No one usually comes to these workshops because these usually don’t exist in southern Alameda County,” said Chris Cara, youth services director of Filipino Advocates for Justice, at an immigrant rights session held last Thursday night in Union City, a city of about 75,000 on the southeast edge of San Francisco Bay. Of the 20 people who showed up to the gymnasium of the Our Lady of the Rosary Church, 5 identified themselves as DACA recipients.

Emerita Alvarado, one of the workshop’s organizers, said that after the October 5 deadline, the focus would shift to helping those who did not qualify for renewal and other immigrants without legal status. “This is a moment not just for the DACA recipients but those who didn’t even qualify to receive that status,” said Alvarado, who belongs to a newly formed group called Union City Dreamers. “In the end, we are all dreamers.”

“Was the need for a better life a crime?” asked Alvarado, who emigrated from El Salvador with her parents when she was 15. “Was my parents’ choice to migrate for survival a crime? And my dreams of becoming a lawyer—are they a crime, too?” Alvarado, 27, and had received her DACA renewal earlier in the week.

At his consultation in San Jose, Quintana was advised to wait and see what happens next. That could mean waiting for a solution from Congress, such as the still undefined deal between Trump and congressional Democrats to protect DACA recipients, or the 15-year path to citizenship proposed under the Republican-backed SUCCEED Act. Or it could mean waiting for a decision in one of the five federal lawsuits challenging the end of DACA.

If that doesn’t work out, Quintana may have to take action on his own. He and his girlfriend have known each other for five years, but have only been dating for one. She’s a citizen, and he said they’ve discussed marriage briefly—on election night. If DACA isn’t saved, they may have to take the next step in their relationship earlier than expected. “It feels like too much pressure to deal with,” Quintana said, “but it’s the only option.”