A crowd gathers around the Forrest monument in Memphis in 1906.

First, it should be big, the plaque. Not necessarily because there is so much to say, though there is so much to say, but big enough to be noticed on the side of this rather grand monument, after they move it and the bodies beneath it across town to the cemetery. And not just big for the sake of bigness. It should stick out as something off, something that disrupts the admirable balance of the statue, currently so tasteful, regal even. This bronze man on this bronze horse. Goatee. Square jaw. You get it. You’ve seen it before, even if you haven’t seen it before. Anyway, the plaque has to be big enough to catch your eye when you’re checking your cellphone or walking your dog or eating a chicken Caesar salad from a plastic box on a bench, or whatever people are doing there in the cemetery, and whatever they might do there in the future, because that’s why we make these things, right? Plaques? Bronze men on bronze horses? We want people in the future to remember.

But first we want them to notice.

This essay is adapted from this episode of The Memory Palace podcast.

So let’s think about material for this imagined plaque. Maybe the plaque should be garish. Not intentionally ugly, not necessarily, but, like, titanium maybe. A patch of Frank Gehry futurism on this staid, stately old thing. It would catch the light and catch the eye, in contrast to the brown-green man on his brown-green horse or a gray pigeon alit on his brown-green shoulder. And I like that the Gehry of it all, the futurism, is not at all futuristic. It’s millennial. A decade from now it’ll be dated, literally dated. Bilbao or Disney Hall or wherever will seem so late ’90s, so 2000s, and you’ll scoff. And I want that. I want this plaque to be fixed in time to let people know when it went up, to let people know what was up at the time.

Because that is the point here; the point of this plaque is to make these future people realize that this lovely old statue wasn’t always old and wasn’t always here in this cemetery. And moreover, I want the reader, standing there in the shadow cast by the late, somehow still lamented Nathan Bedford Forrest on some future summer Sunday, to know why it wound up in a park on the other side of town in the first place. Because memorials aren’t memories. They don’t just appear upon death. A letter of surrender, signed in some farmhouse at the edge of some battlefield, doesn’t come complete with a historic marker affixed to the door.

The monument to Nathan Bedford Forrest was put in that park downtown for a reason, at a specific moment in time. And at that time, General Forrest and Mrs. Forrest were already buried in Elmwood Cemetery. The same place the City Council recently voted to put them. His body, her body, were originally dug up from the ground because a group of prominent Memphians thought they were better off somewhere else.

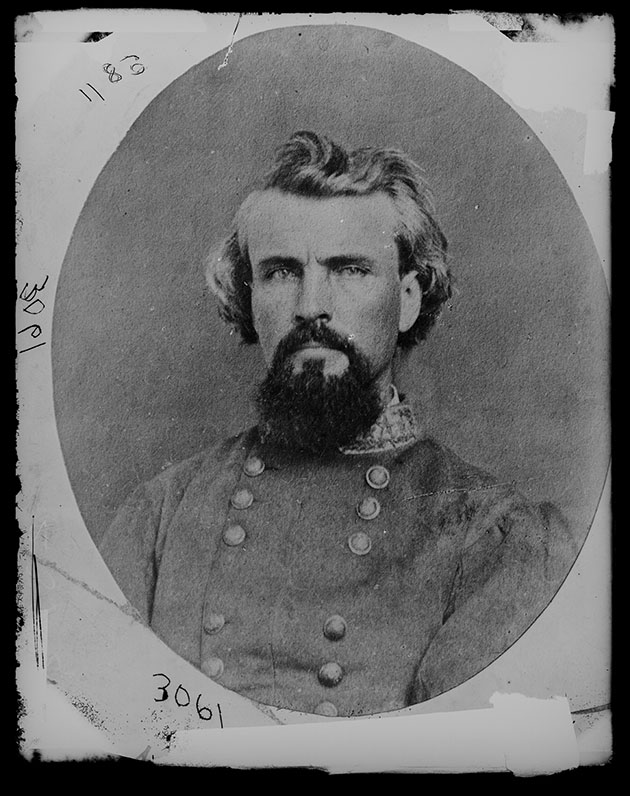

Portrait of General Nathan Bedford Forrest

This was 1905. Forty years after the war. Thirty years after Forrest’s death. They felt the city needed Nathan Bedford Forrest right then because they had seen the city fall from great heights. Memphis had been left relatively unscathed by the war, but not by its outcome. Not by the end of the slave trade, which had been one of the economic and cultural pillars of the city. Without the slave markets selling men and women and children, and without the riverboats and crews and suppliers and dockworkers sending them up and down the river, Memphis was hardly Memphis anymore.

And then there was the yellow fever, which had swept through Memphis some years before and killed so many. And drove many more away, people who never returned after a mandatory evacuation. And now it was the turn of the next century and the city was increasingly—let’s just say it, let’s just stop not saying things—increasingly black, and increasingly tense. White businesses did not like competing with black businesses; black people did not like being lynched.

This move to move Forrest started not long after Ida B. Wells, a Memphian, too, had started writing, rabble-rousing, boldly, bravely, against lynching. After her friend Thomas Moss was improperly imprisoned. After a fight between children over a game of marbles escalated until adults were threatening to burn down his store, and after Moss wound up being pulled from that prison and lynched. And Wells was threatened so much, so often, that she moved away, and the paper she had written for was burned to the ground.

So wealthy white Memphis found all of this unpleasant. So they raised money, $33,000, not to rebuild that newspaper office or build a police force that would properly protect all of its citizens, but to make a monument to a man they thought best represented a Memphis they had lost. A man who had risen from nothing, a blacksmith’s boy who became a millionaire and believed so strongly in the Confederate cause that he enlisted as a private and then went on to prove himself to be perhaps the most brilliant military man born on American soil, even if he didn’t fight for America.

Those are facts. That’s a true story.

And they liked what that story said about the American Dream. Even if it wasn’t technically American. Even if Forrest’s fortune was made buying and selling human beings, and selling cotton raised and picked and cleaned and packed by enslaved human beings. Even if the cause for which he employed that military genius was to ensure that men like him could rise up from nothing and make $1 million buying and selling human beings and stealing their lives and their labor.

In 1905, they held a parade at the unveiling of the new statue and made speeches to honor the general. They said nothing of slavery. They said much about heritage. And honor. And chivalry. They said nothing of how Nathan Bedford Forrest had been the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, nothing of the terror it had wrought, nothing of the assassinations or the lynchings, nothing of how it had sought to undermine and overthrow the political order of the nation, the nation that they celebrated, there in Memphis in 1905, when they played “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “Yankee Doodle Dandy” right alongside “Dixie.” They might not have mentioned any of it, but they knew it, knew about Forrest and the Klan. They’d certainly read The Clansman—it was flying off the shelves that year, a novel about heroic men hidden beneath bedsheets, out to save white virtue from black barbarians. It was “a historical romance,” that’s how it billed itself, that looked back longingly to a time not long before, when people were still chivalrous and forthright and gentlemanly, and would stand up against barbarism and miscegenation and instability and stand up for order, private property. Who better to represent what they had lost than Nathan Bedford Forrest? When they weren’t talking about his slaves or his slave trading, they talked about his heroism in battle, though they didn’t talk about the Battle of Fort Pillow, when he had ordered the massacre of hundreds of American troops attempting to surrender, most of them former slaves. They talked about his faith instead. His strapping build. And about their own hopes that future Memphians would gaze upon Nathan Bedford Forrest and be inspired. They even raised some extra cash for a skating rink, so that the white children of Memphis could play nearby in the shadow of this great man and learn from his shining example, though the bronze would turn brown and green as this symbol of all that was good was exposed to the light of the sun and washed by the rain.

There is debate (there is always debate) about what the Klan meant when Forrest was its wizard. About his intentions at Pillow Fort. They say Forrest repented his sins and his crimes on his deathbed. Should that be on the plaque? Should it note his regret? I say no. May it have ruined him. May it have corroded him like rain on bronze. May it have choked him, like smoke from the crosses and homes and churches burned by men who revered him decades and decades later. Revered him, at least in part, because some influential Memphians decided they needed to revere him in this way in that park in 1905.

So the plaque should be big. But it can’t be big enough to say all that. Maybe it should just say—maybe they should all say, the many, many thousands of Confederate memorials and monuments and markers—that the men who fought and died for the Confederate States of America, whatever their personal reasons, whatever was in their hearts, did so on behalf of a government formed for the express purpose of ensuring that men and women and children could be bought and sold and destroyed at will.

Maybe that should be enough.

But I want people to know about those Memphians in 1905 who wanted people to remember Forrest and why. Who wanted a symbol to hold up and revere. To stand for what they valued most. I want people to know that the statue stood in downtown Memphis for more than 110 years. And to remember that memorials aren’t memories. They have motives. They are historical. They are not history itself.

And I want them to know that in 2015, after Clementa Pinckney and Sharonda Coleman Singleton and Tywanza Sanders and Ethel Lance and Susie Jackson and Cynthia Hurd and Myra Thompson and Daniel Simmons Sr. and DePayne Middleton-Doctor were murdered in a church in Charleston, South Carolina, there were people in Memphis who were done with symbols and ready to bury Nathan Bedford Forrest for good.

Epilogue: After nine members of a black church in Charleston were murdered by a white supremacist in 2015, the Memphis City Council unanimously voted to move Forrest’s statue—one of 40 public memorials to him still found in the South—to Elmwood Cemetery, and this episode of The Memory Palace aired. But the Tennessee Historical Commission overruled that decision, and the statue remained. This summer, after white supremacists rallied in Charlottesville, Virginia (and were praised by President Donald Trump as “very fine people“), Memphis city officials again voted to move the statue, and the mayor threatened to sue any state agency that tried to prevent them from doing so.

Update, Dec. 20, 2017, 11:52 p.m. ET: The Memphis City Council voted unanimously to sell the park where the Nathan Bedford Forrest statue stood in order to finally take down the Confederate statue. It was removed immediately following the vote.