You can’t say Andrea Anthony didn’t try. A 37-year-old African American woman with an infectious smile, Anthony had voted in every major election since she was 18. On November 8, 2016, she went to the Clinton Rose Senior Center, her polling site on the predominantly black north side of Milwaukee, to cast a ballot for Hillary Clinton. “Voting is important to me because I know I have a little, teeny, tiny voice, but that is a way for it to be heard,” she said. “Even though it’s one vote, I feel it needs to count.”

Listen to this story:

She’d lost her driver’s license a few days earlier, but she came prepared with an expired Wisconsin state ID and proof of residency. A poll worker confirmed she was registered to vote at her current address. But this was Wisconsin’s first major election that required voters—even those who were already registered—to present a current driver’s license, passport, or state or military ID to cast a ballot. Anthony couldn’t, and so she wasn’t able to vote.

The poll worker gave her a provisional ballot instead. It would be counted only if she went to the Department of Motor Vehicles to get a new ID and then to the city clerk’s office to confirm her vote, all within 72 hours of Election Day. But Anthony couldn’t take time off from her job as an administrative assistant at a housing management company, and she had five kids and two grandkids to look after. For the first time in her life, her vote wasn’t counted.

I met Anthony on a rainy Wednesday evening in mid-August. She had recently moved to Madison for a job making sales calls for the health insurance company Humana and was living in an Econo Lodge off the freeway with two of her kids and her mother-in-law as she looked for permanent housing. “This particular election was very important to me,” she told me in the motel’s small lobby, citing her strong aversion to Donald Trump. “I felt like the right to vote was being stripped away from me.”

Anthony said her 19-year-old daughter and 21-year-old nephew, who didn’t drive regularly and had misplaced their licenses, were also stymied by the new law. “It was their first election, and they were really excited to vote,” she said. But they didn’t go to the polls because they knew their votes wouldn’t count. Both had planned to vote for Clinton.

On election night, Anthony was shocked to see Trump carry Wisconsin by nearly 23,000 votes. The state, which ranked second in the nation in voter participation in 2008 and 2012, saw its lowest turnout since 2000. More than half the state’s decline in turnout occurred in Milwaukee, which Clinton carried by a 77-18 margin, but where almost 41,000 fewer people voted in 2016 than in 2012. Turnout fell only slightly in white middle-class areas of the city but plunged in black ones. In Anthony’s old district, where aging houses on quiet tree-lined streets are interspersed with boarded-up buildings and vacant lots, turnout dropped by 23 percent from 2012. This is where Clinton lost the state and, with it, the larger narrative about the election.

Clinton’s stunning loss in Wisconsin was blamed on her failure to campaign in the state, and the depressed turnout was attributed to a lack of enthusiasm for either candidate. “Perhaps the biggest drags on voter turnout in Milwaukee, as in the rest of the country, were the candidates themselves,” Sabrina Tavernise of the New York Times wrote in a post-election dispatch that typified this line of analysis. “To some, it was like having to choose between broccoli and liver.”

A New Study Shows Just How Many Americans Were Blocked From Voting in Wisconsin Last Year

The impact of Wisconsin’s voter ID law received almost no attention. When it did, it was often dismissive. Two days after the election, Talking Points Memo ran a piece by University of California-Irvine law professor Rick Hasen under the headline “Democrats Blame ‘Voter Suppression’ for Clinton Loss at Their Peril.” Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker said it was “a load of crap” to claim that the voter ID law had led to lower turnout. When Clinton, in an interview with New York magazine, said her loss was “aided and abetted by the suppression of the vote, particularly in Wisconsin,” the Washington Examiner responded, “Hillary Clinton Blames Voter Suppression for Losing a State She Didn’t Visit Once During the Election.” As the months went on, pundits on the right and left turned Clinton’s loss into a case study for her campaign’s incompetence and the Democratic Party’s broader abandonment of the white working class. Voter suppression efforts were practically ignored, when they weren’t mocked.

Stories like Anthony’s went largely unreported. An analysis by Media Matters for America found that only 8.9 percent of TV news segments on voting rights from July 2016 to June 2017 “discussed the impact voter suppression laws had on the 2016 election,” while more than 70 percent “were about Trump’s false claims of voter fraud and noncitizen voting.” During the 2016 campaign, there were 25 presidential debates but not a single question about voter suppression. The media has spent countless hours interviewing Trump voters but almost no time reporting on disenfranchised voters like Anthony.

Three years after Wisconsin passed its voter ID law in 2011, a federal judge blocked it, noting that 9 percent of all registered voters did not have the required forms of ID. Black voters were about 50 percent likelier than whites to lack these IDs because they were less likely to drive or to be able to afford the documents required to get a current ID, and more likely to have moved from out of state. There is, of course, no one thing that swung the election. Clinton’s failings, James Comey’s 11th-hour letter, Russian interference, fake news, sexism, racism, and a struggling economy in key swing states all contributed to Trump’s victory. We will never be able to assign exact proportions to all the factors at play. But a year later, interviews with voters, organizers, and election officials reveal that, in Wisconsin and beyond, voter suppression played a much larger role than is commonly understood.

Andrea Anthony

Hossein Fatemi

Republicans said the ID law was necessary to stop voter fraud, blaming alleged improprieties at the polls in Milwaukee for narrow losses in the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections. But when the measure was challenged in court, the state couldn’t present a single case of voter impersonation that the law would have stopped. “It is absolutely clear that [the law] will prevent more legitimate votes from being cast than fraudulent votes,” Judge Lynn Adelman wrote in a 2014 decision striking down the law. Adelman’s ruling was overturned by a conservative appeals court panel, which called Wisconsin’s law “materially identical” to a voter ID law in Indiana upheld by the Supreme Court in 2008, even though Wisconsin’s law was much stricter. The panel said the state had “revised the procedures” to make it easier for voters to obtain a voter ID, which reduced “the likelihood of irreparable injury.” Many more rounds of legal challenges ensued, but the law was allowed to stand for the 2016 election.

After the election, registered voters in Milwaukee County and Madison’s Dane County were surveyed about why they didn’t cast a ballot. Eleven percent cited the voter ID law and said they didn’t have an acceptable ID; of those, more than half said the law was the “main reason” they didn’t vote. According to the study’s author, University of Wisconsin-Madison political scientist Kenneth Mayer, that finding implies that between 12,000 and 23,000 registered voters in Madison and Milwaukee—and as many as 45,000 statewide—were deterred from voting by the ID law. “We have hard evidence there were tens of thousands of people who were unable to vote because of the voter ID law,” he says.

Its impact was particularly acute in Milwaukee, where nearly two-thirds of the state’s African Americans live, 37 percent of them below the poverty line. Milwaukee is the most segregated city in the nation, divided between low-income black areas and middle-class white ones. It was known as the “Selma of the North” in the 1960s because of fierce clashes over desegregation. George Wallace once said that if he had to leave Alabama, “I’d want to live on the south side of Milwaukee.”

Neil Albrecht, Milwaukee’s election director, believes that the voter ID law and other changes passed by the Republican Legislature contributed significantly to lower turnout. Albrecht is 55 but seems younger, with bookish tortoise-frame glasses and salt-and-pepper stubble. (“I looked 12 until I became an election administrator,” he joked.) At his office in City Hall with views of the Milwaukee River, Albrecht showed me a color-coded map of the city’s districts, pointing out the ones where turnout had declined the most, including Anthony’s. Next to his desk was a poster that listed “Acceptable Forms of Photo ID.”

“I would estimate that 25 to 35 percent of the 41,000 decrease in voters, or somewhere between 10,000 and 15,000 voters, likely did not vote due to the photo ID requirement,” he said later. “It is very probable that between the photo ID law and the changes to voter registration, enough people were prevented from voting to have changed the outcome of the presidential election in Wisconsin.”

These Three Lawyers Are Quietly Purging Voter Rolls Across the Country

A post-election study by Priorities USA, a Democratic super-PAC that supported Clinton, found that in 2016, turnout decreased by 1.7 percent in the three states that adopted stricter voter ID laws but increased by 1.3 percent in states where ID laws did not change. Wisconsin’s turnout dropped 3.3 percent. If Wisconsin had seen the same turnout increase as states whose laws stayed the same, “we estimate that over 200,000 more voters would have voted in Wisconsin in 2016,” the study said. These “lost voters”—those who voted in 2012 and 2014 but not 2016—”skewed more African American and more Democrat” than the overall voting population. Some academics criticized the study’s methodology, but its conclusions were consistent with a report from the Government Accountability Office, which found that strict voter ID laws in Kansas and Tennessee had decreased turnout by roughly 2 to 3 percent, with the largest drops among black, young, and new voters.

According to a comprehensive study by MIT political scientist Charles Stewart, an estimated 16 million people—12 percent of all voters—encountered at least one problem voting in 2016. There were more than 1 million lost votes, Stewart estimates, because people ran into things like ID laws, long lines at the polls, and difficulty registering. Trump won the election by a total of 78,000 votes in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

In Wisconsin, the intent of those who pushed for the ID law was clear. On the night of Wisconsin’s 2016 primary, GOP Rep. Glenn Grothman, a backer of the law when he was in the state Senate, predicted that a Republican would carry the state in November, even though Wisconsin had gone for Barack Obama by 7 points in 2012. “I think Hillary Clinton is about the weakest candidate the Democrats have ever put up,” he told a local TV news reporter, “and now we have photo ID, and I think photo ID is going to make a little bit of a difference as well.”

The strategy worked. While we’ll never know precisely how many people were prevented from voting, it’s safe to say that thousands of Wisconsinites like Anthony were denied one of their most fundamental rights. And with Republicans now in control of both the executive and legislative branches in the federal government and a majority of states, that problem will likely get worse.

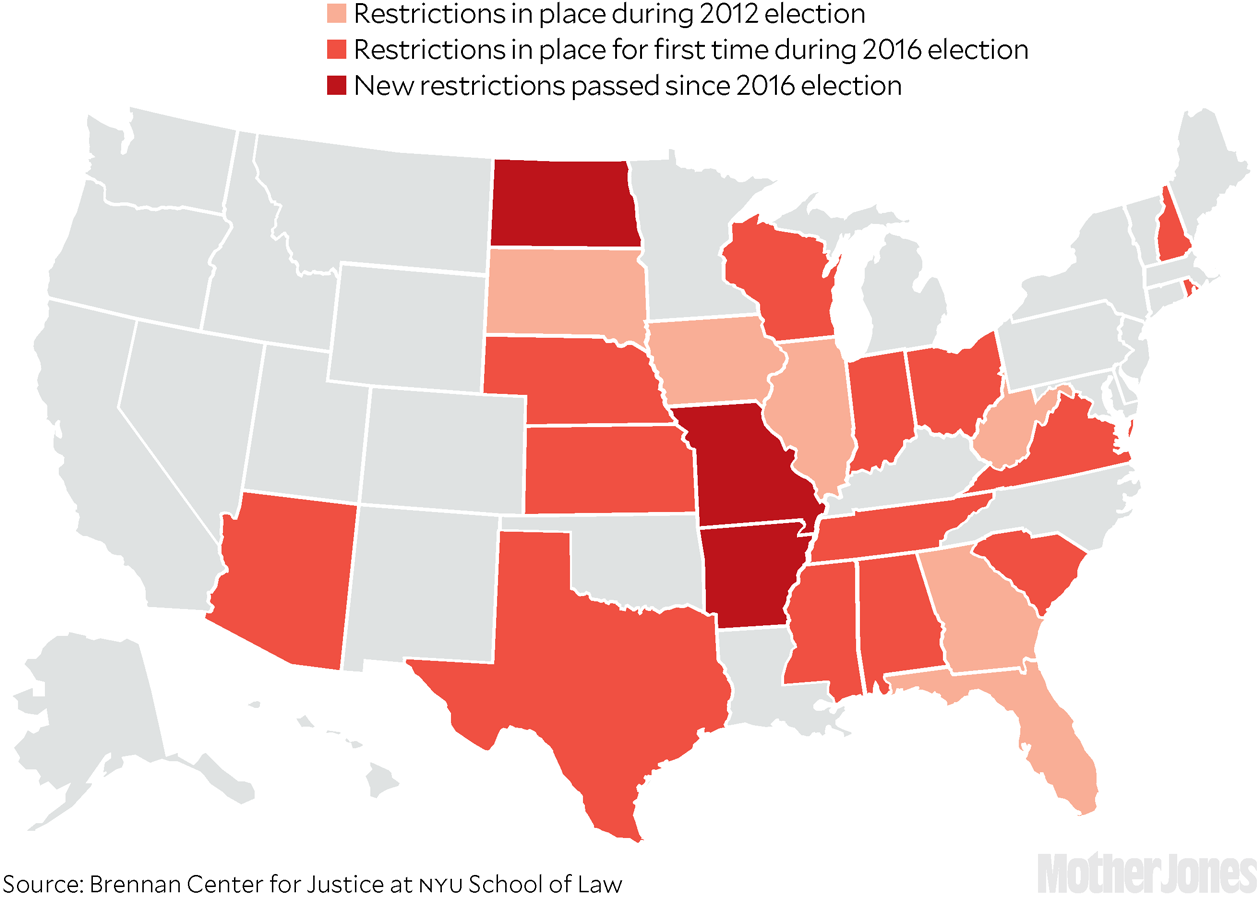

From the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 to the election of our first black president in 2008, the United States saw a gradual increase in voting access. Wisconsin had a particularly proud history of high voter turnout and expansive voting laws, adopting pioneering measures like Election Day registration in the 1970s. But when Republicans took control of 26 state legislatures in the wave election of 2010, they passed a slew of laws making it harder to vote. Twenty-two states have adopted new voting restrictions since then, more than half of which first went into effect in 2016. Wisconsin followed this pattern after Scott Walker became governor in 2011 and began his crusade to remake the state in the conservative image. One of the first projects he and the GOP Legislature undertook was enacting some of the most onerous voting laws in the country.

In other states, the rollback of voting protections was aided by the Supreme Court, which in 2013 gutted the Voting Rights Act, ruling that nine primarily Southern states—and cities and counties in six others—with long histories of voting discrimination no longer had to clear new election rules with the federal government. The 2016 election was the first presidential contest in more than 50 years without the full protections of the Voting Rights Act.

A month after the Supreme Court ruling, North Carolina passed a sweeping rewrite of its election laws, requiring voter IDs, cutting early voting, and eliminating same-day registration, among other changes, before the law was struck down in a federal court for targeting black voters “with almost surgical precision.” Ohio repealed the first week of early voting, when African Americans were five times likelier than whites to cast a ballot. Florida barred ex-felons from becoming eligible to vote after serving their time, preventing 1.7 million Floridians from voting in 2016, including 1 in 5 black voting-age residents. Arizona made it a felony for anyone other than a family member or caregiver to collect a voter’s absentee ballot, disproportionately hurting Latino and Native American voters in the state’s rural areas.

The Attack on Voting Rights, State-by-State

“We’re moving into a pre-Voting Rights Act era, where there isn’t any real watchdogging of elections and changes to election laws,” says Albrecht. “States, including Wisconsin, are making maverick changes that have a significant impact on populations that have been historically disenfranchised. “The GOP shows no signs of letting up on its campaign to restrict voting rights. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has reversed the Obama administration’s opposition to a restrictive voter ID law in Texas and voter purging in Ohio. And the request by Trump’s Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity for the voter data of every American has led thousands of voters to unregister in swing states like Colorado and sparked fears that the administration will propose new policies to undermine access to the ballot at the federal and state levels. Emboldened by these efforts, Republican-controlled statehouses have already passed more voting restrictions in 2017 than they did in 2016 and 2015 combined. Taken together, “there’s no doubt that these election changes affected the turnout among young voters, first-time voters, voters of color, and other members of the Obama coalition that overwhelmingly supported Hillary Clinton,” says Marc Elias, general counsel for Clinton’s campaign, who filed a half-dozen voting rights lawsuits in the months before the 2016 election.

Control of Congress in 2018, not to mention the presidential election in 2020, hinges in part on states like Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, New Hampshire, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Virginia that have put new voting restrictions in place. The lesson from 2016 is terrifyingly clear: If voter suppression can work in a state like Wisconsin, with a long progressive history and a culture of high civic participation, it can work anywhere. And if those who believe in fair elections don’t start to take this threat seriously, history will repeat itself.

Molly McGrath first became a voting rights advocate when she was named Miss Wisconsin in 2004 and traveled to 150 high schools across the state to talk about the importance of casting a ballot. “When we all go into the voting booth that day, it’s one of the only times we’re all equal,” she says. McGrath, 35, has long brown hair and exudes a small-town gregariousness; she’s a native of Wisconsin Rapids, population 18,000. She graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison before becoming a lawyer in New York. But in 2015, after reading and hearing about the effects of Wisconsin’s voter ID law, she returned home to work for VoteRiders, which helps people get the documents they need to vote, trading in the dresses of a beauty queen for the jeans and T-shirt of an organizer. “I always thought I would move back to Wisconsin to do something expansive on voting rights, like helping 17-year-olds vote in local elections,” McGrath said when we met in Madison. “I never thought I’d come back and hear stories of our most vulnerable residents being disenfranchised.”

With Claims of Rampant Voter Fraud, Trump Election Commission Lays the Groundwork for New Restrictions

On September 22, 2016, McGrath accompanied Zack Moore to the DMV on the east side of Madison in her well-traveled blue Acura to get a photo ID. Moore, a 34-year-old African American who’d recently moved from Chicago, worked at a car wash and in landscaping until he broke his leg playing basketball, lost his job, and became homeless. He kept an even keel despite his tough circumstances and had met McGrath at a church breakfast a few weeks earlier, asking whether she could help him vote in the upcoming election.

Moore, who has high cheekbones and a trim beard, came prepared with his Illinois photo ID, his Social Security card, and a pay stub for proof of residence. But he didn’t have a copy of his birth certificate, which had been misplaced by his sister in Illinois. “I’m trying to get a Wisconsin ID so I can vote,” Moore told the clerk. “I don’t have my birth certificate, but I got everything else.” Despite a sign at the DMV that said, “No Birth Certificate? No Problem!” the DMV wouldn’t give Moore a voter ID.

Under the terms of a court order resulting from ongoing litigation over the voter ID law, within six business days the DMV should have given Moore a credential he could use for voting. Instead, a clerk told him to go down to Illinois, get his birth certificate, and come back to the DMV. That would cost Moore money he didn’t have. If he entered Wisconsin’s ID Petition Process, it would take six to eight weeks for him to get a voter ID and he most likely would not be able to vote on Election Day.

“Oh my gosh,” McGrath told Moore, her voice shaking, as they exited. “They’re not following the law.” She turned on her cellphone camera and asked Moore to recount what had just happened.

“I’m disappointed in the government,” Moore said wearily. “I guess they’re trying to keep people from voting.”

Molly McGrath

Lauren Justice

That’s what McGrath was hoping to prove. She had secretly recorded the DMV employees to show that the state was not complying with a court order to distribute voter IDs within a week to people like Moore who did not have access to their birth certificates or other required documents.

A few weeks earlier, US District Judge James Peterson, who oversaw the implementation of the voter ID law, had found that Wisconsin’s process for issuing IDs was a “wretched failure” that “has disenfranchised a number of citizens who are unquestionably qualified to vote.” Eighty-five percent of those denied IDs by the DMV were black or Latino, he noted in his ruling. The roster of people denied IDs bordered on the surreal: a man born in a concentration camp in Germany who’d lost his birth certificate in a fire; a woman who’d lost use of her hands but was not permitted to grant her daughter power of attorney to sign the necessary documents at the DMV; a 90-year-old veteran of Iwo Jima who could not vote with his veteran’s ID. One woman who died while waiting for an ID was listed as a “customer-initiated cancellation” by the DMV.

“Wisconsin may adopt a strict voter ID system only if that system has a well-functioning safety net,” Peterson concluded, ordering the state to “promptly” issue voter IDs to anyone who entered the ID Petition Process.

The same day McGrath and Moore visited the DMV, Wisconsin assured the court that such a safety net was in place, pointing to a Department of Transportation press release stating, “DMV will now be issuing photo identification receipts no later than six business days from receipt of the petition application.” The month prior, the Wisconsin Elections Commission had issued a similar release titled “Free Photo ID for Voting Now Available With One Trip to DMV.”

But McGrath was skeptical. She enlisted her parents, who visited 11 DMVs across the state over the next two weeks to test what would happen to voters like Moore who did not have a birth certificate and wanted to get an ID. In recordings of those encounters, DMV workers said it would “take quite a while” to get the credentials needed to vote, and that it was “hard to predict” when that would be. Only 3 of the 11 DMVs confirmed they would issue a voter ID in a week or less, as the court had ordered.

McGrath gave the recordings to me (I worked at The Nation at the time) and a reporter at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. When the stories came out, Judge Peterson ordered an immediate investigation. “There was really, as far as I can tell, no effort made…to inform the public,” Peterson said. He called the DMV’s voter ID training “manifestly inadequate” and said, “Undeniably there are people who have been disenfranchised.”

It might be tempting to chalk up interactions like Moore’s to the general hellish nature of a trip to the DMV. But by this point, there was already plenty of evidence that Wisconsin’s shoddy implementation of the law was a feature, not a bug.

In the trial that Peterson presided over, Todd Allbaugh, a former chief of staff for state Sen. Dale Schultz, a moderate Republican, described the discussions preceding the law’s passage. When Republican legislators debated the bill behind closed doors in 2011, he recounted, state Sen. Mary Lazich rose from her chair, smacked the table, and said, “We’ve got to think about what this could mean for the neighborhoods around Milwaukee and the college campuses around the state.” Schultz expressed concern about disenfranchising African American and younger voters, but Glenn Grothman, then a state senator and now a member of Congress, cut him off: “What I’m concerned about is winning. We better get this done while we have the opportunity.” Allbaugh testified that at least two other GOP senators were “giddy” and “politically frothing at the mouth” over the bill, including state Sen. Leah Vukmir, the board chair of the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council, which had helped draft voter ID laws in Wisconsin and other states.

After the law passed, the GOP-dominated Legislature disbanded the nonpartisan agency tasked with overseeing state elections and educating the public about the law, replacing it with a commission of partisan appointees. The law was quickly tied up in court, but after it was reinstated in 2014, the Legislature didn’t allocate any funds for voter ID advertising until June 2016.* “The state did virtually nothing to reach out and educate communities in poverty around the photo ID law,” Albrecht said. Wisconsin reported that it was running ads about the law in 52 movie theaters across the state, but not one of those was in Milwaukee. Anyway, Albrecht asks, “how often do people in poverty go to the movies?”

It wasn’t just poor African Americans who were disenfranchised. Most college IDs were not accepted under the law because they didn’t require signatures or have the state-mandated two-year expiration date—a criterion that made little sense at four-year schools. Only 3 of the 13 four-year schools in the University of Wisconsin system had IDs compliant with the new law.

That meant many schools, including UW-Madison, had to issue separate IDs for students to use only for voting, an expensive and confusing process for students and administrators. In addition to needing these new IDs to vote, students at private colleges and universities had to bring them to register to vote as well, in addition to a proof-of-enrollment form. (Public university students needed either the ID or the proof of enrollment.)* There were more than 13,000 out-of-state students at UW-Madison alone who were eligible to vote but couldn’t do so without going through this byzantine process if they lacked a Wisconsin driver’s license or state ID. (UW-Madison ultimately issued more than 7,300 voter IDs for the 2016 general election.)

The voter ID law was one of 33 election changes passed in Wisconsin after Walker took office, and it dovetailed with his signature push to dismantle unions, taking away his opponents’ most effective organizing tool. Wisconsin’s Legislature cut early voting from 30 days to 12, reduced early voting hours on nights and weekends, and restricted early voting to one location per municipality, hampering voters in large urban areas and sprawling rural ones.* It also added new residency requirements for voter registration, eliminated staffers who led statewide registration drives, and made it harder to count absentee ballots.

Republicans were explicit about the purposes of these changes as well. On the floor of the state Senate, Grothman said of extended early voting hours in heavily Democratic cities like Madison and Milwaukee, “I want to nip this in the bud before too many other cities get on board.” (Roughly 514,000 Wisconsinites voted early in 2012; they favored Obama over Mitt Romney by 58 to 41 percent, according to exit polls.) The county clerk of conservative Waukesha County said early voting gave “too much access” to voters in Milwaukee and Madison. Judge Peterson later ruled the early voting cuts had been passed “to suppress the reliably Democratic vote of Milwaukee’s African Americans.”

“The Wisconsin experience,” Peterson said, “demonstrates that a preoccupation with mostly phantom election fraud leads to real incidents of disenfranchisement, which undermine rather than enhance confidence in elections, particularly in minority communities.”

Put together, the changes were a slow-motion train wreck on Election Day for voters like Zack Moore and Andrea Anthony, a pileup many saw coming but nobody was able or willing to stop.

After the election, voting rights groups realized that litigating against voting restrictions wasn’t sufficient. Too often, as in Wisconsin, laws were upheld by conservative judges, and even decisions ending the restrictions sometimes didn’t filter down to voters, who remained confused by dizzying changes to election laws. “We decided to expand and go on offense more,” says Dale Ho, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Voting Rights Project. “We’ve really seen ourselves in the last four years as first responders—a new voter suppression law is passed, whether it’s in Ohio or Wisconsin or Kansas or North Carolina, and then we fly in and try to get the situation under control. We’ve decided it’s not sufficient to wait until those problems happen. We have to attack the system as it exists.”

So the ACLU, which has seen its membership quadruple to 1.6 million since the election, and a collection of startups have mounted registration and organizing campaigns of the sort that ACORN used to do, before the community activist group dissolved in 2010 following attacks by conservative provocateur James O’Keefe—an underappreciated victory in the GOP’s war on ballot access.

“I’m here to make it easy for you to vote, because they’re passing laws to make it hard for you to vote,” she told the roughly 30 people eating breakfast. She’d already helped half a dozen of them get IDs. In July, the ACLU hired McGrath to head its voter ID outreach program. Every week she attends a breakfast for low-income residents at First United Methodist Church in downtown Madison, blocks from the Capitol. On a Wednesday morning in mid-August, she wore a white ACLU T-shirt that said “Let People Vote.”

At a breakfast the week before, she had connected with April Lowe, a 37-year-old African American woman who moved from Chicago last year. Lowe, who had been living in and out of homelessness, didn’t have the proof of residency required to register in Wisconsin, and her Illinois state ID wouldn’t allow her to vote. “I thought my regular state ID from Chicago would be fine here in Wisconsin, but apparently no one explained to me what proper ID I needed,” said Lowe, who had to sit out the November 2016 election.

“This is the first election I didn’t vote in,” she said. Like Andrea Anthony and Zack Moore, she’d wanted to vote for Clinton. “The election probably would have turned out different if everyone had a right, or the chance, to vote.”

McGrath and Lowe set out for the DMV, where McGrath takes people every week. “I used to joke that the DMV was my office,” she said. “Like the bar in Cheers—I would walk in and everyone knows my name.” Lowe had her apartment lease, bills, Illinois ID, and original tattered birth certificate, which her sister had mailed from Illinois.

After waiting for an hour to see the clerk, Lowe walked out with a receipt for a new Wisconsin state ID. “I’m officially a Wisconsin resident now,” she said, smiling. “I want to vote, even if it’s just a little election. I want to vote for whatever I can vote for.”

Without McGrath’s assistance, Lowe probably wouldn’t have registered or gotten a Wisconsin ID. The ACLU hired McGrath to “really help people on the ground in a direct way,” says Ho, and put a focus on organizing. McGrath plans to train activists in other states with suppressive voting laws. “We can’t expect the courts to save us,” says Ho. “It’s not enough to make the rules of elections more fair. We have to do everything we can to encourage civic participation.” Other new nonprofits like Spread the Vote, which has chapters in Virginia and Georgia, are also helping voters in states with strict ID laws.

Jason Kander—the former Missouri secretary of state and Afghanistan veteran known for his 2016 Senate campaign ad in which he assembled a rifle while blindfolded—agrees that the case against voting restrictions can’t just be made in court. “The approach in the past has been nearly exclusively a legal strategy,” says Kander, who founded Let America Vote, a voting rights nonprofit, after the election. “Now with Jeff Sessions in charge of the Justice Department and Trump appointing judges, it means there’s an urgency to engage in a political argument. We need to expand our argument beyond the court of law into the court of public opinion. It has been a politically consequence-free exercise for vote suppressors. That has to change.”

Let America Vote plans to open field offices in Georgia, Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire, and Tennessee in 2018 and to focus on electing pro-voting-rights candidates for state legislature, secretary of state, and governor. The group has signed up more than 65,000 volunteers and placed more than 100 interns and staffers in Virginia, which has a strict voter ID law, for the 2017 gubernatorial and legislative elections, with a goal of contacting half a million voters. “We’re saying, ‘If you’re going to make it harder to vote, we’re going to make it a lot harder for you to get reelected,'” Kander says.

An expanded electorate should help candidates who pledge to promote voting rights. But it’ll take an army of McGraths to get it done. “There’s a lot of opportunity to expand this work,” she says. Ho likes to quote former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall: “The legal system can force open doors, and sometimes even knock down walls. But it cannot build bridges. That job belongs to you and me.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to clarify the timing of the period during which the Legislature did not allocate funds for voter ID advertising.

Clarification: An earlier version of this article did not distinguish between the documents required for public and private university students to register to vote.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the jurisdictions to which the early voting restriction applied.