On a chilly winter morning in a tiny pocket of Silicon Valley known as North Fair Oaks, Everest Public High School is buzzing with energy. Out front, a tall, skinny teen jumps out of a black Porsche SUV; moments later, three young women in matching black hoodies stream out of the front seat of a Toyota pickup that’s filled with trowels, buckets, and a ladder.

I head inside—past the minimalist garden, the modern wood paneling, and the soaring glass foyer—and down the hall to Room 207, where I’d been observing a popular English teacher named Jenny Macho lead AP Literature classes the past couple of weeks. When I arrive, she is sitting at the front of the class with 15-year-old sophomore Marisol Vega while 20 other students are scattered throughout the room, peering at the screens of their school-issued black Google Chromebooks.

Once a week, Marisol and her classmates have what the school calls “personalized-learning time,” a dedicated six-hour slot when students work on individual assignments and receive one-on-one tutoring from their designated faculty mentor. Her leg nervously bouncing under the table, Marisol tells Macho she’s been struggling with Things Fall Apart, the novel by Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe that her class started reading last week, and it’s got her stressed out about her world literature essay that’s due soon. Together, they decide that Marisol should meet with her English teacher, Ms. Nelson, and she sets about writing an email to schedule an appointment during office hours. Meanwhile, senior Michelle Villagomez waits her turn nearby, watching a video in which Macho discusses how authors use word choice to alter the meaning, tone, and mood of a text.

Everest High’s Jenny Macho

Preston Gannaway

I’ve been visiting Everest High—nestled among low-slung bungalows and local shops with names like Peña Meat and Food Market, Morales Custom Upholstery, and Librería Cristiana—because it’s part of Summit Public Schools, a charter network founded in Redwood City in 2003 that has emerged as one of the new leaders of an educational trend known as personalized learning. While there are disagreements over its exact definition, personalized learning generally means that students spend significant time working on different assignments tailored to their needs, can progress through content at their own pace, and have some agency over what and how they learn.

Its champions—including typically private Montessori and Waldorf schools, as well as pockets of progressive teachers in traditional public schools—claim that personalized learning stands in contrast to the familiar classroom structures born in the industrial age: students learning mostly from lectures and textbooks, practicing assignments on identical worksheets, and being sorted based on age or perceived ability measured by narrow metrics. Summit’s additional wrinkle—that it marries personalized learning with new technology—has drawn the attention of education leaders, policy makers, and enthusiastic tech billionaires.

As Macho and Michelle discuss her academic progress, they add new goals to her digital profile using software called the Summit Learning Platform. Designed in partnership with Facebook—founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, pediatrician Priscilla Chan, have been working with Summit since 2014—the software provides students with a daily overview of their responsibilities and progress, which are marked against their yearly personalized academic goals. It does so by centralizing every student’s various goals, assignments, drafts, tests, self-reflections, grades, and feedback from their teachers—making a bet that such an immediate and continuous feedback loop promotes student ownership over their own learning. The platform also aims to promote more individualized learning experiences: Students who complete all assignments can take on additional tasks and stretch themselves, and those who struggle can request extra tutoring.

The software is a crucial part of Summit’s approach—and an increasingly important component of personalized learning in schools around the country. The big bet, which is still largely an untested hypothesis, is that tech can both increase engagement and independence among students and bring certain efficiencies, including cost savings, into curriculum planning, assessment, and scheduling. In theory, this would allow teachers to spend more time providing individualized instruction, even in cash-strapped public schools. Since 2014, 330 schools in 40 states have signed up to adopt the Summit model.

Students arrive for the start of class at Everest High.

Preston Gannaway

In a recent speech, Zuckerberg said he plans to “upgrade” the majority of about 25,000 public middle and high schools over the next decade. He and Chan have also pledged to donate “hundreds of millions of dollars per year” to bring personalized learning to other schools through the new Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, set up to donate and invest their Facebook shares—valued at about $45 billion in 2016—to causes related to education and science. They aren’t alone: Bill Gates’ foundation has committed $300 million to the movement since 2009, and Netflix founder Reed Hastings has invested at least $11 million into personalized math software.

It was against this backdrop that some of the most powerful supporters of the charter school movement gathered in May at a major education summit outside San Francisco. Unlike the year before, when race and equity were the focus, the key themes in 2017 were tech-based “schools of tomorrow” and personalized learning. Around the same time, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos touched on similar ideas at the yearly gathering of the American Federation for Children, an advocacy group promoting vouchers, charters, and virtual schools that she chaired and helped fund before joining President Donald Trump’s Cabinet. “We stand on the verge of the most significant opportunity we have ever had to drag American education out of the Stone Age and into the future,” DeVos said.

To be sure, advocates pushing for more personalization from across the political spectrum have plenty of evidence that today’s classrooms need an upgrade: Year after year, the National Survey of High School Student Engagement shows that almost three-quarters of kids find their classes lacking in challenge or relevance to modern life. A 2013 Gallup Poll that surveyed more than 600,000 US students found that engagement drops precipitously between grades 5 and 12. And students from black, Latino, and poor families have had the least access to intellectually challenging and engaging classrooms thanks in part to racial segregation and tracking, which means that, even in diverse schools, white and Asian American students are far more likely to be sorted into more advanced classes.

Many educators have told me over the years that although parents and policymakers say they want personalized, student-centered education, most major incentives and penalties are attached to outcomes on standardized tests. Teachers in high-poverty schools point out that personalized instruction is difficult to provide in large classrooms, and with very few paid hours dedicated for planning and grading individually tailored assignments. In a 2008 national survey commissioned by the Fordham Institute, more than 8 in 10 teachers said “differentiated instruction”—educational jargon for personalized teaching—was “very” or “somewhat difficult” to implement.

Tech is supposed to help solve some of these long-standing tensions. Summit leaders believe certain mini-lectures and basic assessments can be offloaded to computers, allowing educators to focus their limited classroom time on mentoring and teaching of complex skills, such as analyzing texts, deriving meaning, thinking critically, engaging in thoughtful discussions, and working on group tasks.

Still, research on the effectiveness of tech-infused approaches to personalized learning is thin, and results are mixed. Critics argue that until there is more research, schools should not experiment on children, and instead should invest in traditional, evidence-based approaches like high-quality training and coaching of teachers and manageable class sizes that allow for individualized attention. Others worry about a lack of transparency and public input with often-untested tech products entering classrooms under the “personalized learning” badge at a dizzying pace. (The ed tech market is estimated to reach $21 billion by 2020.)

During the same week that DeVos argued for more personalization earlier this year, the Trump administration proposed more than a 13 percent cut in the federal budget for schools. With more and more districts strapped for cash, personalized learning grants from tech-driven foundations will start to look increasingly seductive to principals and superintendents alike. So while many current education debates center around vouchers, the various forces moving into schools under the badge of personalization could have much farther-reaching consequences for public education in the next decade.

Soon after Summit founder Diane Tavenner received her teaching credential in 1994, she started working at Hawthorne High School in Los Angeles, where 90 percent of students were kids of color, 90 percent were poor, and 90 percent were learning English. The year she got there, she told me, more kids had dropped out of the senior class than would go on to graduate.

Tavenner was 22 and had no teaching experience or coaching support. The portable classroom where she worked was located right next to the bathrooms, the site of frequent fights. “My students were amazing human beings,” Tavenner recalled when I met her in Summit’s Redwood City office, about a 10-minute drive from Facebook’s headquarters in Menlo Park. “But they were in an environment that was set up for their failure. It was a very unsafe place for kids—physically and emotionally.”

Summit founder and CEO Diane Tavenner

Preston Gannaway

The following year, Tavenner and a few of her colleagues took 70 incoming freshmen with the lowest grades and poor attendance in middle school and created a small academy. Rather than putting them into remedial math and English, Tavenner and her colleagues designed more challenging college prep classes. Teachers spent extra time building strong relationships and providing one-on-one tutoring. Two years later, no academy students had dropped out.

But soon athletic coaches started requesting afternoons for practice, and the schedule changed. The new arrangement, Tavenner said, made it impossible to keep the academy students together with the same teachers. “I felt so disillusioned,” she said. “I realized there are all of these entrenched interests that prevent anything from changing.”

After three more years of what Tavenner says felt like “2 steps forward and 10 backward,” she quit Hawthorne and considered leaving teaching all together. Eventually, she moved to Silicon Valley and started working at a high school in suburban Mountain View. The school was more integrated racially and socioeconomically, but like in most other middle and high schools nationally, most Latino and low-income students were “tracked” into less challenging classes. These students didn’t have opportunities to complete required courses for state universities and couldn’t take honors and AP classes. Because so many don’t fulfill these state requirements, one study found that almost 75 percent of Latino students in California and two-thirds of black students can only attend community colleges, and very few of them transfer to four-year universities. Tavenner wanted to design a better model, one without tracking, and enrolled in a Stanford University graduate program for prospective principals in education policy, leadership, and organization.

While at Stanford, Tavenner took two classes that would guide her thinking for years. The first was with Larry Cuban, a high school history teacher turned education professor whose work describes how two competing educational philosophies—efficiency-driven reform and student-centered, personalized education—have been locked in battle since the beginning of the 20th century. The efficiency camp has pushed for teaching specific knowledge and skills easily measured by tests that would prepare students for “useful” future roles, which invariably were circumscribed by race and class. The student-centered camp, however, is inspired by the work of educators like John Dewey, Anna Julia Cooper, and others who believed that schools have to develop multiple dimensions of a human being: intellectual, emotional, social, cultural, civic, and creative. Authentic learning, they argue, takes place when kids engage in tasks that mimic real-world activities rather than worksheets, when students have some choice over what they are learning, and when classrooms are set up for high emotional, intellectual, and creative engagement.

The following year, Tavenner took a class with influential education researcher Linda Darling-Hammond, whose work focuses on the reduction of racial disparities in schools and the importance of highly trained and adequately coached teachers, integrated classrooms, and “culturally relevant pedagogy.” This research-based approach argues that many students of color have negative experiences in schools—and society—that undermine their own conception of their intellect, and that schools should be set up as intentional communities to combat this self-doubt. A large body of research demonstrates that integrated schools that don’t use tracking and do employ diverse, well-trained teachers and have curriculum that doesn’t force students to reject their home cultures have shown significant increases in achievement. (The United States made its largest gains in closing gaps in math and reading scores between white and black students at the peak of integration, between 1970 and 1988.)

Tavenner went on to start the first Summit school—Summit Preparatory Charter, in Redwood City—in 2003, and those two courses provided the foundation of its philosophy and early designs, which centered around training teachers, keeping classes small, and emphasizing projects and mentorship, all in racially and socioeconomically integrated classrooms that strive to build academic rigor through warm relationships and a sense of community. (Currently, 44 percent of students at Summit schools are Latino, 20 percent are white, 11 percent are Asian American, 6 percent are black, 11 percent are English learners, and 50 percent are low-income.) And Summit Prep was successful from the start: Over its first decade, 96 percent of graduates were accepted to four-year colleges, and by 2011, Newsweek had ranked it among the top 10 high schools in the nation for its success with Latino and poor students.

But even as students thrived and Tavenner began opening more Summit schools around the Bay Area, administrators started learning that high school success wasn’t translating once Summit students headed off to college. In 2011, when Tavenner and her team surveyed students from their first class, the responses depressed them: Only a little more than half were on track to graduate.

When Summit surveyed their graduates who’d dropped out of college, Tavenner found that most were overwhelmed with obstacles in large institutions that didn’t provide intense one-on-one support like Summit schools did. If that safety net typically disappeared in college, she posited, Summit needed to better teach self-reliance. While many researchers agree that most of the obstacles students encounter in college stem from economic inequities and the history of racial exclusion in the United States, studies show that certain skills and mindsets can help students cope with some setbacks they encounter in academic settings. Over time, these “habits of success”—including breaking up large projects into smaller, manageable goals; monitoring your own learning progress; seeking help, self-reflection, and self-awareness; and managing priorities and time effectively—became part of the larger vision of “self-directed learning” at Summit.

At the time, much of Summit’s data about students—their academic and personal goals, progress updates, analysis of strengths and challenges, student work, and teacher feedback—lived on paper in file cabinets. Tavenner wanted to move all data online and make it available to students and teachers every day, arguing that the ability to track and access it would increase student engagement in their own learning process, promote self-reliance, and help teachers improve instruction. So in 2013, Summit hired its first on-site engineer to start developing an online platform to turn the data over to students and teachers. When Mark Zuckerberg visited Summit that year, he asked Tavenner how he could help; eventually, Facebook began providing free engineering support, which led to the Summit Learning Platform.

Meanwhile, Tavenner also had discovered that about a third of Summit grads had to take remedial classes, mostly in math, when they got to college. Research suggests that students who do are much less likely to graduate. Tavenner decided that Summit had to get better at filling knowledge gaps and fluency, and that’s when she first looked for help from the nonprofit Khan Academy, which produces free YouTube lectures, mostly in math and science, including practice exercises and assessments. Tavenner reasoned that offloading some lectures and worksheets would open up extra time for teaching higher-order skills, individual mentoring, analyzing student data, and curriculum planning. Personalized learning requires more time for planning, and a typical American teacher has just three to five hours a week for planning and collaboration. (Teachers in Finland, Singapore, and South Korea spend 15 to 25 hours each week working to improve their craft.)

At two new schools in San Jose, Summit used Khan’s online tutorials to help ninth-graders learn math. A year later, two-thirds of Summit’s San Jose ninth-graders achieved higher growth than the national average on one type of standardized test, and the lowest-performing students showed the fastest growth, according to Summit. San Jose math teachers also reported more engagement among students, who said they liked the immediate results from Khan Academy assessments.

Meanwhile, engineers continued tweaking the data aggregation software. When students log into their platforms today, they see a sequence of boxes representing content area “playlists”—including online texts, video lectures, and interactive practice problems—that they can move through at their own pace. In AP Literature, there was a total of eight content playlists curated by Macho and other English teachers that students had to study during their personalized-learning time, including one on the Greek and Latin roots of English vocabulary.

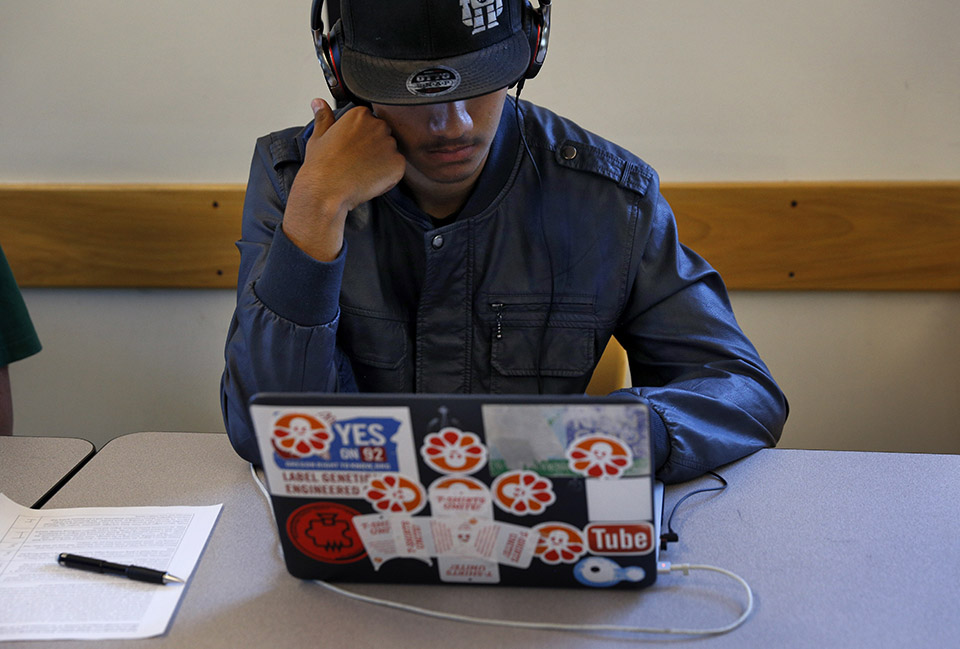

Manuel Zaragoza-Huato writes an essay during his AP Literature class at Everest High.

Preston Gannaway

When students come back to class from personalized-learning time, Summit teachers say they don’t have to spend as much time delivering basic content through lectures and can spend that time instead facilitating projects and group work assignments that ask students to apply complex skills. At Summit, students spend about 15 to 20 hours in “project time” each week; in Macho’s AP Lit, for example, Michelle Villagomez wrote an explication of a poem by Elizabeth Bishop in which she relied on two new strategies she learned through playlists: decoding complex words using Greek and Latin roots and analyzing how a pattern of words affected the meaning and tone of the poem. Content learned through playlists is assessed through online tests in all classes and grades and is worth 30 percent of the grade; project-time assessments graded by teachers are worth 70 percent.

Teachers can access student data on a daily basis and make adjustments to their lessons the following day. The platform can also notify teachers when students struggle in particular areas, so teachers can design appropriate interventions; according to Macho, it also allows for easy, efficient ways of communicating this feedback to students.

Summit is now offering the platform for free to other teachers and administrators. It comes with two weeks of subsidized training and occasional regional trainings, coaching, and tech troubleshooting. The platform includes lesson plans with projects, playlists, and assessments, but educators in other schools can customize it by creating new playlists and projects or adding additional materials. The partnership currently includes 330 schools nationwide, 75 percent of which are traditional public schools and 20 percent of which are charters.

Since Summit started working with other schools three years ago, 90 percent of them have remained in the program, and nearly 90 percent of surveyed teachers said they would recommend the program to other schools. According to Summit’s surveys, teachers reported increased attendance and better behavior in their classrooms, and the majority of teachers reported their students improved as “self-directed learners, who can set goals and make a plan to achieve them.”

Tavenner argues that the main goal of the platform is not to copy and paste Summit’s curriculum or even its model to other schools; it’s about collective iteration and sharing of best practices in personalized learning. “Every teacher doesn’t have to be by themselves in the classroom re-creating the wheel over and over,” she said. “We can collaborate and build a world-class curriculum together. So, they are not spending hundreds of hours planning, scoring, grading, busy work. We tried to get rid of that, so their time is focused on high-leverage, high-value work with kids. What you see is our best effort at designing that at scale.”

Still, many researchers and educators, including some former Summit teachers, remain skeptical that the infusion of tech leads to authentic learning or higher achievement. Julian Cortella was one of a small group of early teachers who left Summit, in part because he was concerned by the outcomes of the pilots he observed in San Jose. He was working at low-tech Summit Prep at the time, and that year his school still posted higher state test scores in math than Summit’s San Jose schools, even though the pilot schools were spending more time on math each day.

A former mechanical engineer who spent significant time working in Silicon Valley startups, Cortella is not against technology in the classrooms. Instead, he says his 13 years of hands-on classroom experience tell him that the tech enthusiasts rely too much on untested assumptions. Cortella, who now teaches at an all-girls private school in Palo Alto, says he has tried a variety of ways to incorporate video lectures and various software in his lessons, but he found other methods—the power of human explanation, his own lesson-planning judgment, and the use of a pen and paper to work through math problems—were more effective. (Some evidence shows that students understand longer texts better in print than digitally and comprehend lectures more deeply if they take notes by hand instead of on a laptop.) “I hope that Summit can prove me wrong,” he said, “but I wish we kept one school with the original model in place so that we could compare the two approaches.”

When asked why Summit didn’t keep one school without computers, Tavenner replied that the vision behind the model was never about increases in standardized test scores alone. Summit is continuously evolving to provide a coherent, evidence-based model for addressing a variety of needs and skills students require for success in the 21st century, she said, including complex cognitive and life skills that are not easily captured by test scores.

Most researchers and advocates who work in the field of personalized learning told me that they don’t consider Summit a tech-heavy model. But social interactions can be lacking at schools where students spend most of their time learning online. Benjamin Riley, who as the former director of policy and advocacy for the NewSchools Venture Fund visited many tech-driven schools, was surprised to see how little students talked and worked together in most schools he observed. “Learning is such a social activity, but tech-driven classrooms are really quiet,” says Riley, who now runs Deans for Impact, a nonprofit he founded to improve teacher training. Meanwhile, John Hattie, an education professor at Australia’s University of Melbourne, analyzed nearly 1,200 studies and ranked various strategies according to their influence on student achievement. Hattie ranks “cooperative learning”—studying in groups, participating in discussions, explaining concepts to your peers, working on complex problems with other students—as having one of the highest effect sizes on learning.

A former math teacher and the current chief academic officer of Desmos—a tech startup most known for its free, online calculator Summit teachers incorporate in their lesson plans—Dan Meyer thinks of the Summit model as one of the most thoughtful and promising in the ed-tech world. But like Riley, Meyer is deeply concerned about what he has observed in most other classrooms that use technology. “Personalized pacing and bubble tests is how I’d summarize most of the ed-tech field,” he said. “You get your own bubble test—one that is on your level. We have seen students with headphones on, sitting in call-center-type cubicles, stacked up to 100 students. Maybe it’s efficient, but efficient toward what ends?”

Jenny Macho helps student James Poe during AP English Literature class at Summit Everest Public High School in Redwood City, Calif., Thursday, October 26, 2017. The charter school network is at the forefront of personalized learning and incorporating technology.

Preston Gannaway

More broadly, Meyer is concerned about what he views as various questionable pedagogical practices that seep into classrooms using the badge of personalized learning. Meyer thinks that enthusiasts of Khan-style online lectures—which can be rewinded for those who didn’t understand the material—overstate their effectiveness, arguing that if any of his students didn’t understand how he explained something, he’d gather additional data from the student and change his lecture.

And then there are less known examples that didn’t live up to their initial hype. Five years ago, the tech-heavy Carpe Diem Collegiate High School and Middle School in Yuma, Arizona, was touted as one of the most promising charter models for raising test scores and busting the industrial-age model. About 226 students sat in individual cubicles in a large room and worked at their own pace using online curriculum provided by a for-profit company. Critics called it a test-prep factory that overlooked important skills not captured by online bubble tests. And while test scores were higher than the district average, so was student attrition. The school struggled with attracting enough students and eventually ran into financial problems. This year, the original campus that in 2012 was upheld as a leader of personalized learning lost its charter.

Around the same time Carpe Diem was receiving glowing reports about its scores, Detroit schools—under the leadership of a state-appointed emergency manager and the Eastern Michigan University Board of Regents—brought untested products developed by a for-profit corporation to about 10,000 mostly poor and African American students in the name of personalized learning. When teachers reported that the software was “horrendous,” “slow,” poorly designed, and incomplete, the plan to take the approach statewide was abandoned.

In part because there is so much disagreement over the definition of tech-infused personalized instruction, Tavenner and her team have stripped it from the title of their program, which they say is designed and driven by teachers. It is now called Summit Learning, and in August the organization released a 70-page paper explaining the latest research in cognitive science, pedagogy, and psychology that informed the guiding philosophy behind the organization’s comprehensive approach. Still, there are very few studies on specific personalization strategies that incorporate tech, and findings are often inconclusive. And though there are several positive briefs written by think tanks and consulting firms about Summit, none is a rigorous study by independent academic institutions.

Nationally, a 2017 study from the RAND Corporation funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation looked at 40 schools implementing tech-infused personalized-learning programs—all also funded by Gates—for at least one year. While researchers found that personalized learning did lead to modest gains in test scores, none of the schools trying out the approach looked that different from traditional ones: Teachers tailored lessons to individual students to a similar degree, and students had roughly the same amount of choices in the classrooms compared with traditional schools. On top of that, educators complained they didn’t have enough time to plan individualized lessons, and that the constraints of standardized outcomes to measure success made personalization difficult. Researchers concluded that the latest trend in education “may not work everywhere, and it requires careful thought about the context that enables it to work well.”

While working on an upcoming book last year, Stanford’s Larry Cuban observed 41 Silicon Valley teachers recommended as the best examples of educators integrating technology into their lesson plans. Nine teachers in his study were at Summit. Cuban found that technology was in the background at Summit, used by skilled teachers to achieve very specific goals. He observed teachers working hard to improve online curriculum based on what they saw in students’ work. Compared with other schools Cuban observed, Summit students spent plenty of time in collaborative settings in and out of classrooms.

Reflecting on all schools he observed, Cuban told me that just like 100 years ago, roughly two competing visions of what good education means are still battling out today. But he found a major difference: The efficiency-minded tech reformers are co-opting the language of personalized learning. As an example, Cuban described Teach to One, a popular middle school math program in which students spend most of their time learning online. The instruction was heavily skills-based and was solely focused on what’s going to be on the tests, Cuban observed. The knowledge and skills are packaged mostly by software designers. “They call it personalized,” he said, “but it was deeply committed to the efficiency view to get kids prepared for multiple-choice tests.”

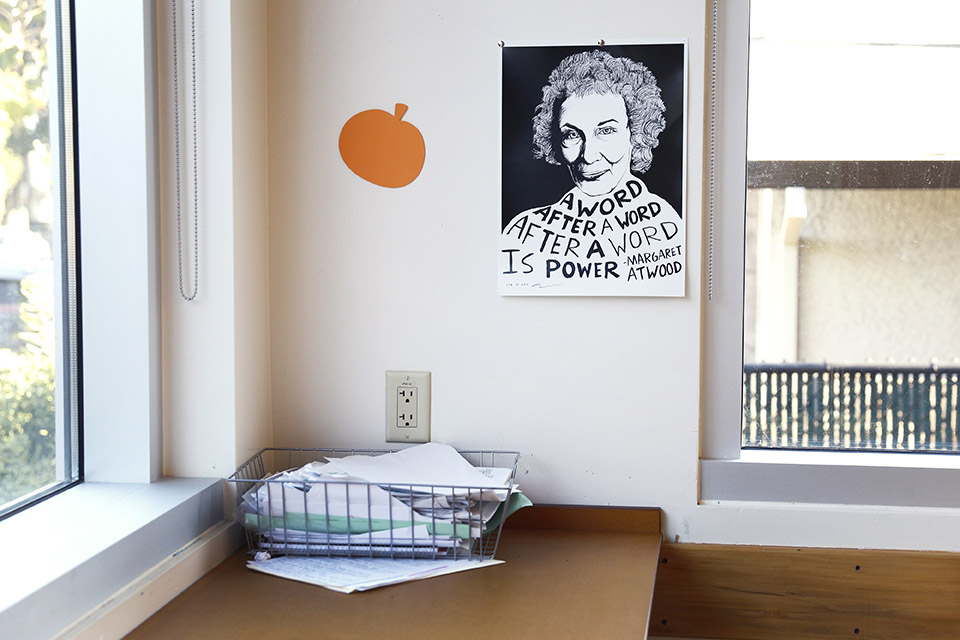

Jenny Macho’s classroom at Everest High

Preston Gannaway

Cuban places Summit right in the middle of the two competing wings—calling the network an impressive hybrid that is working thoughtfully to incorporate the best ideas from all camps to deliver high-quality instruction on limited public funds. Cuban told me one of Summit’s key strengths is its skilled, well-trained teachers—teachers get eight weeks of paid time to improve their craft during the school year, in addition to one paid month during the summer—who use technology to achieve specific goals and their professional judgment to make decisions on how and why certain learning will take place.

For now it’s hard to say conclusively how successful the most recent tech-infused iteration of Summit will be—including the new “habits of success” and emphasis on student ownership over their own learning—until Michelle Villagomez’s class graduates from college. Meanwhile, as tech enthusiasts promote different models to public schools across the country, Cuban cautions in his writing that business leaders, including today’s barons of Silicon Valley, tend to bring strong biases to their educational funding that may not always be in the best interest of society. They often believe, for example, that the primary purpose of schooling should be an efficient preparation of skilled workers for the economy, including the tech industry. And as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative pour ever more cash into America’s schools, other important purposes of public education—from integration to promotion of civic engagement—could start to get crowded out.

Since the field is still in its infancy and enjoys more hype around it than almost any other reform at the moment, it is ripe for abuse and rushed implementation, said Pedro Noguera, a distinguished professor of education at the University of California-Los Angeles and a director of its Center for the Transformation of Schools. “Policymakers and schools,” he said, “should proceed with extreme caution.”

When Michelle Villagomez and I reconnect later in the spring, she has returned from touring colleges. The University of California-Davis was her favorite, she declares smiling, while sipping iced tea at the teachers’ lounge next to the school’s entrance. “The campus feels small, even though it’s not,” she says. “There is a sense of community, just like at Summit.”

Before high school, Michelle, her cousin, and her sister went to a private Catholic school close to nearby Atherton, the third-wealthiest zip code in the country. They were the only three Latino kids there, thanks to generous scholarships, in a school serving mostly white, affluent students. The school was organized in a more traditional model: Teachers lectured or read from the texts, then modeled some exercises at the front of the room in preparation for the tests. When Michelle would repeat the steps at school or at home, she would realize that she didn’t fully absorb everything.

Most of Michelle’s friends could get help at home and they usually progressed smoothly, but Michelle’s parents are immigrants from Mexico, and they couldn’t help her or afford private tutors. On most tests, Michelle got Cs and Fs. “My cousin, sister, and I were always in the least-advanced classes,” she says.

It wasn’t until Michelle had an amazing seventh-grade English teacher that she turned the corner on her reading and writing—and realized the impact the right teacher can have. “At Summit,” she says, “instead of one teacher being your mentor, many are like that.” These mentors, Macho included, have helped build Michelle’s confidence in her abilities. Beyond that, she’s taken advantage of the fact that she can retake tests as many times as she needs to figure out her weak spots and focus on improving in certain areas. Now, she adds, “I’m loving English. I believe in myself. I have confidence to speak up during classes.”

Michelle and I hear laughter and shouting outside our window, as more students cluster at the entrance of the school on their way to morning classes. Seeing Latino and white students learning in the same advanced classes every day is rare, she tells me. “In middle school, I really doubted my intelligence,” she recalls. “None of the Latino kids were in advanced classes, and I thought there was something wrong with me, and my own people. I was ashamed to speak Spanish, because it was viewed as a weakness. Here it’s viewed as a strength.”

Before I leave, I ask her if she will recommend Summit to her cousins and friends. “Absolutely,” she says without a pause. “But Summit is not for everyone. You have to push yourself here. You can settle for passing, or you can push yourself to go further.

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.