Sthanlee Mirador/Sipa USA via AP

Calls for Oprah Winfrey to run for president may have begun as a joke, but in the wake of her rousing Golden Globes speech, speculation has swirled. CNN even ran live updates on a potential “Oprah 2020” campaign on Monday. President Donald Trump told reporters he doubts Winfrey will run, though he also declared he would win a campaign against her.

Some progressives welcomed the idea that Winfrey, a popular media icon whose star power could eclipse even that of Trump, might take on the president in 2020. Winfrey, who endorsed Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, is well know for championing a wide range of important causes, such as promoting reading and founding the Leadership Academy for Girls in Johannesburg, South Africa. But there’s one area in which Winfrey and her would-be opponent are surprisingly alike: Both she and Trump have helped spread the inaccurate—and dangerous—myth that vaccines cause autism or other health problems.

The supposed link between autism and vaccines has been repeatedly and unequivocally debunked by scientists and public health officials. (See here, here, here, here, here and here, for starters.) The theory has roots in an error-filled (and later retracted) 1998 British study claiming a link between autism and vaccines. Following the paper’s publication, measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination rates dropped in Britain, and measles cases rose sharply in the ensuing years. Researchers reported a decline in US vaccination rates. Years later, the discredited theory continues to negatively impact public health.

Winfrey’s role in this controversy dates back to 2007, when she brought Jenny McCarthy, the Playboy model and actress, onto her show to talk about autism. McCarthy’s young son, Evan, had suffered a series of seizures at two-and-a-half years old and was later diagnosed with autism. McCarthy was adamant that the MMR vaccination Evan received as a baby caused his autism. On the show, McCarthy told Oprah she had been instinctually uncomfortable with allowing the doctor to give her son the vaccine. “I said to the doctor, I have a very bad feeling about this shot,” McCarthy recounted. “This is the autism shot, isn’t it?”

On the show, McCarthy’s claims went largely unchallenged. Winfrey praised McCarthy as a “mother warrior” and plugged her book Louder Than Words: A Mother’s Journey in Healing Autism, which inaccurately suggests childhood vaccinations contribute to autism. Winfrey did read a brief statement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which said there was no scientific evidence of a connection and that scientists were continuing to study the causes of autism. “It is important to remember, vaccines protect and save lives. Vaccines protect infants, children and adults from the unnecessary harm and premature death caused by vaccine-preventable diseases,” the CDC statement concluded. But McCarthy had the final word. “My science is named Evan, and he’s at home,” she said. “That’s my science.”

CNN’s Larry King and People magazine also gave attention to McCarthy and her views. She became a semi-regular guest on Winfrey’s show and signed a deal with Winfrey’s Harpo Studios to create her own show, though that show ultimately fell through. McCarthy says she is not anti-vaccine but, rather, an advocate for “safe vaccines.” There’s no evidence that vaccines are currently unsafe.

This wasn’t the first time Winfrey’s audience had been presented with the vaccines-autism theory. A few months before McCarthy’s appearance, Katie Wright, whose son has autism, said on the show, “The vaccine connection has not been refuted at all. In fact, we give 37 vaccines to babies under the age of 18 months. Nobody has shown that that’s safe, a wise idea, the multiple vaccines at once.”

“She wanted to say it, and I wanted you to get it out there,” Winfrey replied, as the audience clapped. “Because you are a mother dealing with your child every day.”

The following year, Christiane Northrup, a physician and one of Winfrey’s regular experts, answered a fan’s question about the human papillomavirus vaccine, which protects against a sexually transmitted virus that can cause cervical cancer. Northrup expressed apprehension about the shot, saying she is “very concerned” about vaccinating young girls and would rather focus on a “getting everybody on a dietary program that would enhance their immunity,” according to a write-up on Winfrey’s website.

“I’m a little against my own profession,” Northrup said. “My own profession feels that everyone should be vaccinated.” (A publicist for Northrup told Mother Jones that she was “unavailable for comment.”)

Oprah’s show has since been criticized for promoting the careers of a number of scientifically dubious guests and offering unsound health advice. “Oprah is a really interesting figure, and she has clearly been a really positive force in so many ways,” says Seth Mnookin, director of MIT’s science writing program and author of The Panic Virus, which discusses anti-vaxxer appearances on Winfrey’s show. “I think public health is not one of those ways, and it’s not just around vaccines.”

In a 2009 statement to Newsweek, Winfrey defended the controversial medical advice offered by guests on her show, arguing that she was empowering viewers to make up their own minds:

“The guests we feature often share their first-person stories in an effort to inform the audience and put a human face on topics relevant to them. I’ve been saying for years that people are responsible for their actions and their own well-being. I believe my viewers understand the medical information presented on the show is just that—information—not an endorsement or prescription. Rather, my intention is for our viewers to take the information and engage in a dialogue with their medical practitioners about what may be right for them.”

Winfrey’s own views on vaccinations aren’t clear. The Oprah Winfrey Network press office didn’t respond to requests for comment. An article published last year on her website did encourage readers to get booster shots recommended by the CDC, including the MMR vaccine. “You may think you’ve had all the immunizations you’ll ever require,” the article said, “but the guidelines are constantly being fine-tuned—for the good of us all.”

Regardless of her personal opinions, it’s evident that she offered anti-vaxxers an opportunity to voice their unfounded concerns on national TV and may not have considered the “long-term ramifications,” says Jennifer Reich, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Colorado Denver and the author of Calling the Shots: Why Parents Reject Vaccines. During the 2007 episode with McCarthy, for instance, Winfrey told viewers McCarthy would appear on a special online messaging board to answer questions, according to Mnookin’s book. On that board, McCarthy wrote, “If I had another child, I would not vaccinate.” When one mother wrote that she had chosen not to vaccinate her child because of the “autism link,” McCarthy replied, “I’m so proud you followed your mommy instinct.”

Still, it’s hard to say for sure how much influence celebrities have over decisions that parents make about vaccinating their children, according to Reich. “It’s not so much that someone is going to go into their pediatrician’s office for an appointment and say, ‘I saw this on Oprah, and I’m going to change what I do,'” she says. “It’s more that they become vehicles to inject this misinformation into the nation’s consciousness.”

“They continue to raise the question that the science is somehow not settled,” adds Reich. “I think public health agencies are struggling with how to combat anecdotes. When a parent says this feels true to me, it’s really hard to stack that feeling against population data.”

If Winfrey did decide to run for president, she’d hardly be the first candidate to have played a role in legitimizing inaccurate fears about vaccines. During the 2008 campaign, Clinton, Obama, and John McCain all suggested that vaccines might cause autism. (So did a 2004 Mother Jones story.)

In 2011, Rep. Michele Bachmann wrongly suggested during a GOP presidential debate that the HPV vaccine can cause mental retardation. More recently, Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky) said vaccines can cause “mental disorders” and are “an issue of freedom.” In the midst of worries about a measles outbreak, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (R) suggested parents should have a choice of whether or not to vaccinate; he later backed off his remarks.

Healthy young child goes to doctor, gets pumped with massive shot of many vaccines, doesn't feel good and changes – AUTISM. Many such cases!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 28, 2014

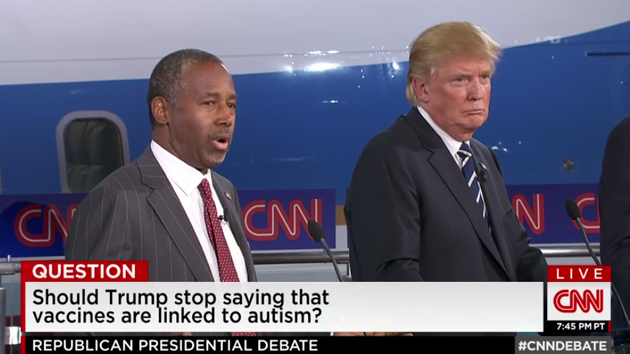

For his part, Trump suggested vaccines were linked to autism during a presidential debate in late 2015, met with anti-vaxxers in 2016, and reportedly asked vaccine skeptic Robert Kennedy Jr. to lead a commission on “vaccine safety” shortly before taking office. (No such commission has been created.)

Most Americans still support vaccinating children. A survey by the Pew Research Center, published in February 2017, found 82 percent of US adults say healthy children should be required to get the MMR vaccine in order to attend school, while just 17 percent say parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their kids. But even a small decline in the percentage of children who are vaccinated can have serious consequences for public health. Last year, Minnesota fought its largest measles outbreak in nearly three decades.

* This story has been revised.