Protesters hold up a sign representing a district in Texas in front of the Supreme Court on October 3, 2017.Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call via AP

This fall, millions of voters will cast ballots in legislative districts that have been deemed unconstitutional. Courts have repeatedly tossed out Republican-drawn electoral maps for excessive gerrymandering, but those maps will remain in effect through November, potentially changing who controls Congress and state legislatures for the next two years.

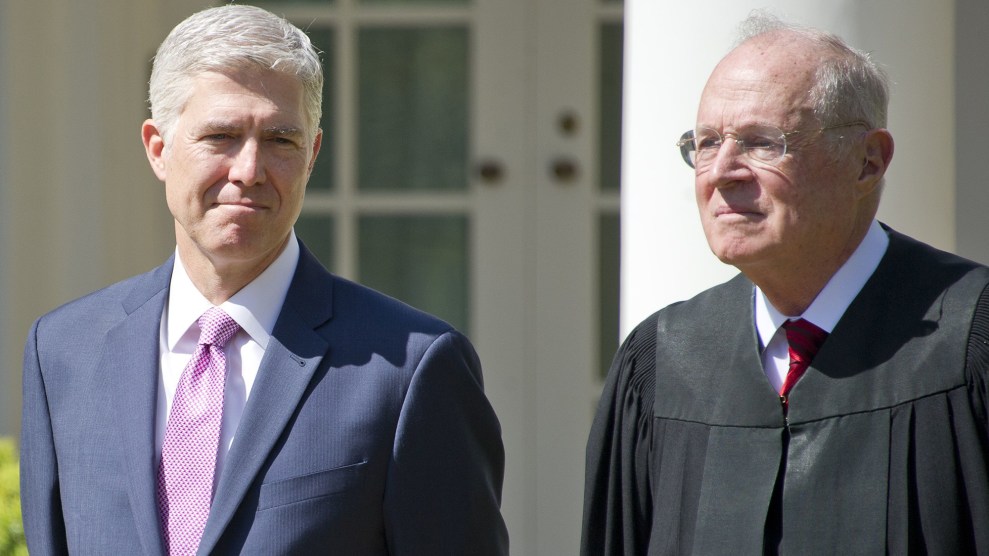

The blame lies with the Supreme Court. In Texas, North Carolina, and Wisconsin, Democratic plaintiffs have successfully convinced federal district courts that their states’ political maps unconstitutional. Those courts have ordered new maps to be drawn. But the Supreme Court has halted that process repeatedly, causing voters to be stuck in unfairly drawn districts for yet another election cycle.

At the beginning of each decade, state legislatures—and, in a few states, independent redistricting commissions—draw new political maps based on the latest census data. Since sweeping into power in Congress and many statehouses in 2010, Republicans have engaged in aggressive gerrymandering across the country, using both racial and partisan voter data to rig the maps in their favor. For the first time, the country is preparing for the next census while still fighting redistricting battles stemming from the last one.

“In many cases, people will have voted under maps that may be unconstitutional in four elections out of the five this decade,” says Michael Li, a voting rights attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice, a research and litigation nonprofit housed at New York University. “That really is extraordinary.”

Take Texas. In 2011, the state’s Republican-controlled legislature drew a congressional map so gerrymandered along racial lines that multiple federal courts blocked its implementation under the 1965 Voting Rights Act, whose “preclearance” provision forced certain states with a history of racial discrimination, like Texas, to have their maps cleared by the Justice Department or a federal court. In place of the illegal 2011 map, a district court in Texas implemented a temporary map for the 2012 elections that was based on the 2011 map and left some discriminatory districts intact. But then, in 2013, when the Supreme Court struck down the preclearance provision of the Voting Rights Act, Texas swiftly made the temporary map permanent. Voting rights groups and voters sued, arguing that the map still contained illegal racial gerrymanders. A federal court in San Antonio ultimately threw out the map last summer for intentionally discriminating against African Americans and Latinos and ordered new maps for the 2018 election cycle.

But last September, the Supreme Court halted the process of drawing new maps. In January, the court added the Texas cases to its winter docket, promising a ruling on the legality of the maps by this summer. At that point, even if the map’s challengers prevail yet again, there will be no time to draw new districts in time for the November midterms. Millions of Texas voters will cast ballots in 2018 in unconstitutional congressional and state legislative districts, even though courts repeatedly tossed them out as racially discriminatory.

In fact, even if the Supreme Court finds the maps unconstitutional, the process of drawing new maps could stretch into 2020, making it possible that Texans will spend an entire decade voting under biased maps before having new ones drawn after the 2020 census. “By the time this case gets done, a child born on the day the Texas case was filed will be nine years old,” says Li. “That’s remarkable.”

Texas is a cautionary tale, highlighting the multiple ways in which the Supreme Court has shaped redistricting litigation to favor legislators who act in bad faith to gerrymander their districts. Rick Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California, Irvine School of Law, blames a Supreme Court doctrine that discourages courts from changing voting laws close to an election to avoid confusion. Originally, the court applied this principle to issues like voter ID laws and precinct closures. But in recent years, he says, it’s crept into redistricting cases, delaying the implementation of new maps by years. “It encourages litigation tactics that stretch things out as long as possible to try to get it to the next election period,” says Hasen. In many district-level elections held every two years, he says, “there’s always an election around the corner.”

Some Republican officials are urging the Supreme Court to expand this principle. Earlier this month, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down the state’s heavily gerrymandered congressional map, and Republicans in the state legislature appealed the decision to the US Supreme Court. In a brief filed in late January, six Republican secretaries of state urged the US Supreme Court to block the redrawing of Pennsylvania’s unconstitutional congressional map for the next two election cycles, until a new post-census map is drawn for 2022, citing the court’s previous willingness to put redrawing on hold. “Simply put, there is no need to hurry,” they wrote. If the Supreme Court agrees, then Pennsylvania will join the list of states where voters will be forced to cast ballots in unconstitutional districts this November.

A partial solution, says Li, would be for the court to stop blocking lower-court orders to draw new maps as it decides whether to uphold the original map. That would mean that once the Supreme Court ruled on a given map, there would be two maps ready to go, and either the old map would be upheld or the new one would be implemented. “If you’re going to put the interest of voters first, then having alternative maps ready to go is a way that you do that,” he says.

The Supreme Court’s decision to end the preclearance process exacerbates the problem. In 2016, after three years of litigation, a federal district court struck down North Carolina’s congressional map for illegally using race to pack African Americans into two bizarrely shaped districts. In response, the Republican-controlled legislature used partisan data to draw a new map that maintained the same electoral advantage as the first map. Earlier this month, a federal court struck down that map as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander and ordered the legislature to draw yet another map. Instead, the legislature appealed to the Supreme Court, which promptly halted the process of drawing up a new map. This unconstitutional map—which Hasen says may not have gotten federal approval under preclearance—is now the most likely map to be used in 2018.

Texas is an even starker example of what could happen in the next round of redistricting without preclearance. At the beginning of the decade, Texas was allotted four new congressional districts based on tremendous population growth. Though 89 percent of new residents were minorities, who vote overwhelmingly Democratic, three of the four new districts created by the state’s 2011 map elected white Republicans. Under preclearance, the court blocked the map, and Texas has operated since then under the less extreme version of it. “In a world where we didn’t have [preclearance] in 2011, Texas would have been able to enact this really aggressive plan and it wouldn’t have been blocked,” says Li. “It’s likely that map would still be in effect today. And that’s really sobering because in the next round of redistricting, there won’t be [preclearance] and maps like Texas’ 2011 congressional map, which was blocked, won’t be blocked.”

Ultimately, the Supreme Court has created a system that rewards legislators who gerrymander. If the party in power wants to gerrymander the districts, there is no downside to drawing an aggressive gerrymander. “You see what you can get away with, and even if the maps ultimately get struck down, you may get a free election or two or three or even four out of it,” says Li. And when a map is invalidated, thanks to Supreme Court precedent going back to the 1970s, the task of redrawing it falls to the legislature. The result is a situation like the one in North Carolina, where Republican legislators—who enjoy a large majority thanks in part to a state legislative map that has been ruled an unconstitutional racial gerrymander—drew an illegal map that remained in place for two election cycles. When it got thrown out, they had the opportunity to redraw it, this time using partisan rather than racial data, and restart the entire process.

“You’ve got state legislators who themselves have been elected in districts that were determined to be an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, drawing an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander to replace districts that were determined to be an unconstitutional racial gerrymander,” says Dan Vicuna, an attorney at the nonprofit Common Cause, which is a plaintiff in one of several cases challenging North Carolina’s congressional map. “It’s really absurd.”