tiwaongin/Getty

During Wednesday night’s CNN town hall on school shootings, Lori Alhadeff, the parent of a 14-year-old victim of the Parkland, Florida, high school shooting, confronted the NRA’s national spokeswoman Dana Loesch on why her organization hadn’t done more to make schools safer. Alhadeff pointed to a 225-page National School Shield Task Force report that the NRA put out after the Sandy Hook Elementary mass shooting, outlining steps the organization said schools could take to protect students from guns. Five years later, she demanded to know why schools were still missing the NRA-suggested protections: “Where are our metal detectors? Where is our bulletproof glass?” she asked. “Where are the lists of things to do and the ability to do them that every school needs to have in order to provide safety for our kids?”

Loesch replied that 150 schools had taken advantage of the NRA’s help on this front, but she said it was ultimately up to the schools to implement the recommendations. The following day, in a speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference, NRA CEO Wayne LaPierre offered schools his organization’s “free” support and guidance to protect themselves, saying that communities “must come together to implement the very best strategy to harden their schools.” President Donald Trump echoed the sentiment Thursday saying, “We have to harden our sites” to protect schools from gun violence.

Before schools start lining up to take advantage of LaPierre’s generosity, it’s worth revisiting exactly what the NRA means when it calls for measures to “harden” a school. Here are a few recommendations from its 2013 task force report:

A big fence

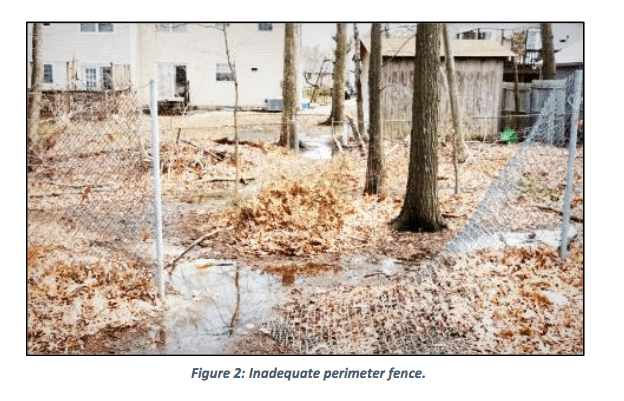

The report identifies perimeter fencing, made with material that “clearly demonstrates territorial ownership,” as the “first physical and psychological barrier that a violent individual must overcome.” According to the report, the fences should not send a psychological message that the school is vulnerable, like this (ordinary school) fence:

Instead, the fence should look more like this prison yard-style fence:

No trees

Research shows that students learn better and are less stressed when they can see some greenery outside the classroom window. But according to the task force, trees and bushes on school grounds should instead be viewed as major security threats. They supposedly provide too many opportunities for a shooter to stash weapons and hide from surveillance cameras. Shrubbery, according to the report, is particularly bad if positioned next to the aforementioned fence, lest all that foliage provide cover to someone cutting through the fence or climbing over it.

If a school insists on landscaping, the NRA recommends very kid-friendly “thorn-bearing and sharp-leaved plant species to create natural physical barriers to deter aggressors.” The report does urge school leaders to keep in mind that such prickly barriers might also prevent people from escaping a mad shooter.

Putting a whole new spin on The Giving Tree, the report notes that trees may have one upside. A stately maple may provide a level of “blast shielding in the event that an offender attempts to utilize explosive devices in an assault on school property.”

No parking lots

The NRA report grudgingly acknowledges that having a place for people and students to park at school is convenient. But that convenience comes at a steep price: “[V]ehicles can provide potential attackers with a means of concealing and transporting weapons, can be used as a tool in overpowering physical security infrastructure, and can even serve as weapons in and of themselves,” the report notes. If a school must allow employees and students to park near the building, the report says, the parking lot should be closely surveilled and ideally patrolled by armed guards.

Entrapment areas

The school receptionist is apparently the first line of defense against any active shooter. Thus the task force recommends that school front offices be protected with two sets of automatically locking doors, preferably constructed with “ballistic protective glass” like the neighborhood liquor store. Such a set up will allow the front office staff to safely trap a potential shooter like a bug in a window screen until help arrives. The report recommends reinforcing the front desk and side wall with “ballistic steel plating” that employees could hide behind should the shooter get past the entrapment area.

No windows

According to the task force report, schools should be designed with an eye toward 1970s-era post-riots urban architecture. Windows, if allowed at all, should be designed solely with surveillance in mind. They should be only large enough to peep out of to assess ongoing threats. “Design windows, framing, and anchoring systems to minimize the effects of explosive blasts, gunfire, and forced entry,” the report urges. The authors do acknowledge that this advice may conflict with the school’s need to provide people fleeing a shooter with a secondary escape route, noting that many people survived the Virginia Tech shooting by climbing out windows. Interior windows, particularly those in classrooms, should be fitted with ballistic glass, if at all feasible.

Nowhere does the report indicate how much its security construction measures might cost the average cash-strapped school district. But one company suggests that outfitting an average school with ballistic glass, at $100 per square foot, would cost at least $1 million.

Never mind that Baltimore schools had to close for lack of heat this winter. And that in 2015, the City Controller deemed crumbling Philadelphia schools, full of cockroaches, leaking pipes, and chronically clogged toilets, a public health emergency. Meanwhile, a lawsuit filed in 2016 over the conditions of Detroit schools noted that the school buildings “impose their own grotesque barriers to learning and teaching, including classroom temperatures ranging from freezing to over 90 degrees, vermin, and unworkable toilets.” The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that US school infrastructure is underfunded by about $38 billion a year. Given all that, it’s not hard to see why schools haven’t sunk more of their budgets into new entrapment areas.

It’s unclear what kind of “free” help LaPierre is offering cash-strapped schools to harden their defenses. Fortunately, the School Shield report offers one affordable security upgrade—equipping all classrooms with one of these:

Big Foot Door Stop

Amazon

Such a device, the report says, can “provide an inexpensive and simple addition to door security during lockdown.” Should your school be unable to afford even a case of Big Foot door stops, the NRA offers this helpful advice: “hide and hope.”