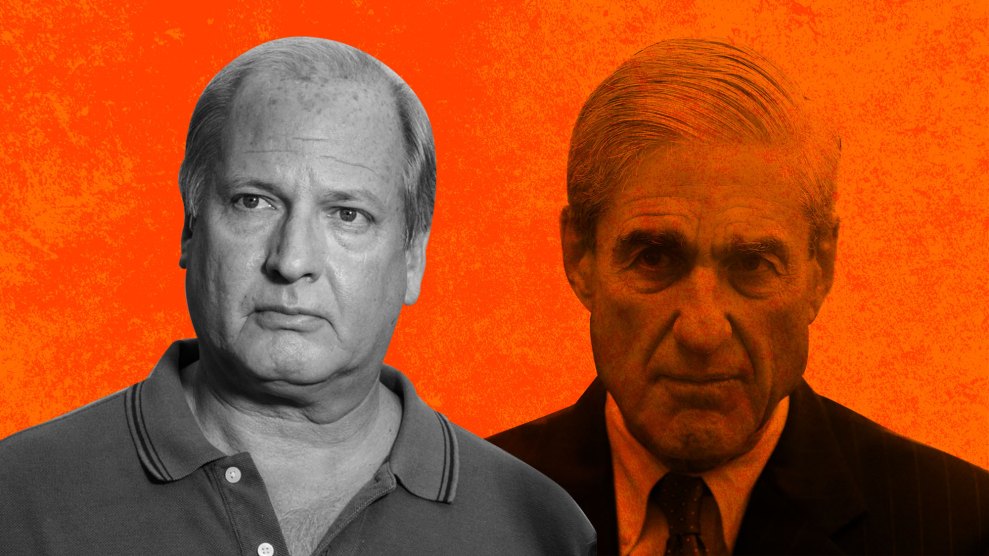

Mother Jones illustration

Last year, Howard “Buck” McKeon, a former Republican congressman who chaired the House Armed Services Committee, was hired to lobby for an Albanian political party seeking access to the Trump administration and congressional Republicans. But most of his firm’s work was bankrolled by a Cypriot shell company called Dorelita Limited. The outfit was created by a Cyprus-based lawyer who specializes in forming offshore corporations and who was affiliated with companies linked to a prominent Russian oligarch. Yet this shell company is now controlled, at least on paper, by an Athens-based attorney who in the past has advised a controversial Greek billionaire. The source of the money that flowed from Dorelita to the McKeon Group, the lobbying shop McKeon established in 2015 after leaving Congress, remains murky. That, in fact, may be the point.

The arrangement raises questions about who paid for US lobbying on behalf of a small Albanian third party called the Socialist Movement for Integration (known by its Albanian abbreviation, LSI) in advance of elections in the country last year. The mysterious deal provides another example of murky interests using offshore entities using the US political system to try to influence Balkan politics. Last month, Mother Jones reported that Nicolas Muzin, a former aide to Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) who also worked for the Trump campaign, was paid by a Scottish shell company with ties to Russian nationals to lobby for the conservative Albanian opposition party.

McKeon’s work for Dorelita also highlights how lax US lobbying laws make it easy for foreign interests to use shell companies and front groups to push their agendas in Washington without disclosing their identities or purposes. And this tale shows how players around the world can utilize shell companies—which can be whipped up in countries that have few disclosure requirements—to anonymously wield political influence in the United States and elsewhere.

“The primary purpose of offshore shell companies in secrecy jurisdictions like Cyprus is to hide sensitive activities,” says Jeffrey Winters, a Northwestern University political scientist who studies financial networks and how the ultra-rich use shell companies. “There are red flags all over this deal.”

“A good and very special relationship”

In January 2017, the McKeon Group signed a $15,000-a-month contract with the LSI, Albania’s third largest political party, to lobby on its behalf in Washington and promote its head, Ilir Meta, then the speaker of the Albanian parliament. At the time, Albania, a majority Muslim country of 2.9 million that borders Greece, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Montenegro, was ramping up for its presidential and parliamentary elections, to take place in April and June 2017, respectively.

The LSI has traditionally played the role of political kingmaker in Albania, and it was then in a coalition government with the ruling Socialist Party of Albania. But this alliance was fraying, and the LSI would soon team up with the right-leaning Democratic Party of Albania (DPA). Meta, meanwhile, was gunning for the presidency, a mostly ceremonial post elected by the parliament. But should Meta win that position, the LSI would gain a political boost.

Meta is a longtime politician who served as Albania’s prime minister from 1999 to 2002. He was controversially acquitted in 2012 of bribery charges stemming from a video that showed him discussing apparently corrupt deals with another former minister. Meta is “perceived by many citizens to be a symbol of corruption,” according to a recent report by Freedom House, a nonprofit watchdog organization based in Washington.

McKeon’s contract with the LSI called for his firm to arrange for Meta to attend Donald Trump’s inauguration and organize meetings with “key DC leaders” during the inaugural festivities. After Trump’s swearing-in, according to the contract, the lobbying firm was to help “develop a good and very special relationship with the incoming Administration and Congress.” The contract was signed not by LSI officials but by an acquaintance of one of the party’s members: an Athens-based lawyer named Iraklis Fidetzis.

In mid-January, Meta traveled to Washington to attend Trump’s inauguration, and during his stay McKeon brokered meetings for the Albanian politician with Republicans including Sens. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and Pat Roberts (R-Kansas) and Reps. Mike Conaway (R-Texas), Mike Turner (R-Ohio), and Ed Royce (R-Calif.), the chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

Washington is full of lobbyists who rep foreign regimes and interests. So it was not odd for the LSI to try to find supporters in Washington. Last year, Albania’s three leading parties each employed lobbyists to cultivate ties with DC politicos. But what is curious is what happened after the McKeon Group reported in February 2017 that it had wrapped up its lobbying contract with the LSI.

The following month, on March 24, the McKeon Group inked another contract signed by Fidetzis—this time to lobby for Dorelita Limited, which listed its “primary offices” at the same address in Athens as Fidetzis’ law firm. A source familiar with the contract said Fidetzis had suggested paying the McKeon Group to continue to work for the LSI through this corporate entity. The new lobbying contract, covering a year of work, paid more than three times what the McKeon Group had earned under its previous deal with the LSI: $50,000 a month, plus expenses.

The source said the primary goal of the Dorelita contract was to get Meta “access to” President Trump, in the form of a meeting or a photo op. That effort failed.

But the contract and other paperwork the McKeon Group filed for its work for Dorelita made no mention of LSI. The registration the firm submitted to the Justice Department under the Foreign Agents Registration Act to represent Dorelita stated only that McKeon’s firm would try “to manage meetings between U.S. government officials and Dorelita Limited.” The paperwork, in other words, suggested that the McKeon Group was lobbying for a company with its own independent agenda. But that was not the case.

“That’s why you use shell companies”

Dorelita, it turned out, was a shell company with what seemed like one purpose: to provide payment for McKeon’s lobbying for the LSI. The firm was incorporated in 2013 by a Greek attorney named Andreas Petrou. He runs a law office in the Cypriot capital of Nicosia that creates and administers shell companies. The firm says about one-third of its clients are Russian, and it advertises a special phone number for Russian speakers. According to Russian and Cypriot business records, Petrou’s firm was involved with Cyprus-based companies that are linked to Oleg Deripaska, the Russian aluminum magnate, whose business relationship with Trump’s indicted campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, has entangled him in the Trump-Russia scandal. Two Deripaska-linked businesses were headquartered at the same address as Petrou’s law firm: EN+ Corporate Services Limited and ACL Aluminum Constructions Limited, where according to Cyprus business records, Petrou was the director. Russian corporate filings note that Petrou was also affiliated with four other Russian businesses that were part of Deripaska’s aluminum empire. Earlier this month, Deripaska and several companies he controls were sanctioned by the Treasury Department.

After Mother Jones sent Rusal, the Moscow-based aluminum conglomerate owned by Deripaska, a list of questions about the oligarch’s ties to Petrou, the company replied by email that the “allegations are false, groundless and defamatory” and threatened legal action. But a spokesperson subsequently confirmed Petrou’s law firm had been hired by one of Deripaska’s companies to provide “corporate and secretarial services.” Deripaska has for years used Cyprus—among other offshore locales—as a corporate home for some of his businesses. The spokesperson denied any connection between Dorelita and Deripaska and said the oligarch had no business interests in Albania.

Mother Jones sent a reporter to Petrou’s office in Cyprus, where a board with brass plates showed the names of about 40 other companies that appear to be registered at the same address. Petrou, who an assistant said was not present, later responded via email. He said he provided “nominee services” for two Deripaska-connected outfits. That means the businesses paid him to serve as a stand-in on paper as an officer or shareholder. Such arrangements may serve to mask a company’s real owners. Petrou said he was ending his firm’s relationship with Deripaska’s businesses due to the recent sanctions imposed on the oligarch and his firms by the US government.

“The main activity of my office for the last 25 years is the incorporation of companies in Cyprus and other jurisdictions abroad and the provision of fiduciary services to our clients as well,” Petrou stated in an email. And he provided some of Dorelita’s backstory. He explained that the company “was kept in our offices as a shelf company”—that is, a ready-made corporation left dormant until it would be sold to a buyer either looking to avoid the hassle of incorporating a new company or seeking an outfit with an established corporate history.

According to Petrou, a banking crisis that hit Cyprus in 2013 sharply reduced demand for his services, “and as a result of this a lot of our shelf companies remained unsold.” Dorelita, he said in an email, was particularly difficult to offload: “Name Dorelita was rejected several times by the clients because as they told me it sounded as the name of a lady dancer in Mexican night club.”

Eventually, he found a buyer. On February 22, 2017, he sold Dorelita to Iakovos Taliadoros, the managing director of a Nicosia-based accounting firm, for 1,000 euros. Petrou said he had no involvement with Dorelita after that “and therefore there is no any knowledge from our side concerning the structure and ownership of the company and its activities.” Taliadoros refused to answer questions about Dorelita.

Shortly after Dorelita changed hands, Iraklis Fidetzis—who Taliadoros confirmed is his client—was named the company’s director. According to the Athens-based law firm of Papaconstantinou & Partners, where Fidetzis serves as of counsel, he specializes in “financial matters and investments” and has “wide and long international experience” in these areas.

Fidetzis, who did not respond to inquiries, has worked as an adviser to Dimitris Kontominas, a Greek billionaire and owner of a television station who was charged in 2016 with tax evasion and money laundering. Kontominas has faced accusations of several alleged financial crimes during his career, without any apparent convictions. A former Macedonian intelligence official said in a 2014 deposition taken by the US Securities and Exchange Commission that Fidetzis was present at a 2005 meeting when Kontominas allegedly arranged to bribe Macedonia’s prime minister and other officials on behalf of a telecommunications company called Magyar Telekom. The alleged bribes were paid through Cypriot shell companies controlled by Kontominas. The SEC investigated the case because the telecommunications company was owned by Deutsche Telekom, at the time traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Deutsche Telekom and Magyar Telekom paid a combined $95 million penalty in 2011 to settle charges that they had violated the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Two former Magyar Telekom executives paid a combined $400,000 in fines in the United States in April 2017 to settle individual cases. Kontominas was not charged.

It was the month after Fidetzis took control of Dorelita in early 2017 that he signed the new lobbying deal between the McKeon Group and the shell company. The lobbying firm’s subsequent filings with the Justice Department provide inconsistent information about its work for Dorelita. In December, the McKeon Group filed a notice with the Justice Department that said it had terminated its representation of Dorelita as of March 28, 2017. But that was the same day the firm registered to work for Dorelita and four days after the contract was signed.

According to this December filing, the lobbying firm severed its ties with the shell company before performing any work. But that was not what happened. In April 2017, the McKeon Group contacted a host of congressional Republicans to set up meetings for Dorelita, according to another filing McKeon submitted to the Justice Department. And multiple sources tell Mother Jones some of these meetings related to the LSI. A spokesman for Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), who met LSI officials, says they “did not appear to have a specific ‘ask’ and it was more of an introduction.” Dorelita, the Lee spokesman said, was not discussed. Lobbying disclosures the McKeon Group filed with Congress stated that the firm continued to represent Dorelita through October 2017. In total, the company reported earning at least $65,000 for its work for Dorelita. It was paid $15,000 by the LSI.

The LSI denies any connection to Dorelita. A spokesman for the party said it had “zero contact with and zero knowledge about” the company. The spokesman noted that a prominent party member, Vangjel Tavo, had connected the party to Fidetzis and that later Tavo approved the $15,000 payment from the LSI to the McKeon Group. A doctor and a member of Albania’s Greek minority, Tavo visited the United States in late April 2017, days before Albania’s parliament elected Meta the country’s president. He was in Washington on the days that McKeon scheduled meetings with members of Congress on behalf of Dorelita, raising the possibility that he may have taken part in these sit-downs. Tavo did not respond to a request for comment.

Arben Cici, who serves as director of cabinet for President Meta, said in an email that Meta since his election has had no relations with lobbyists or “any political force.” Cici did not respond to questions about Meta’s ties to Fidetzis or Dorelita.

McKeon declined to speak to Mother Jones about his firm’s work for the shell company. McKeon’s son, Howard McKeon Jr., who works with his father and was involved in the Albanian project, also would not discuss the matter. McKeon’s wife, Patricia, who is listed as a contact on disclosure documents filed with Congress regarding Dorelita, hung up when contacted by a reporter.

There is no law against accepting payments from a foreign shell company for lobbying, according to experts on lobbying rules. But the Foreign Agents Registration Act does require disclosing the foreign government or political party that is a principal beneficiary of lobbying work—and the McKeon Group did not identify the LSI or Albania as the beneficiary of its work for Dorelita. “If [McKeon] knows, or has every reason to believe, that the work he is doing is really being directed by the party, and they are the real client, then he has got to disclose that,” says Joseph Sandler, a Washington lawyer with expertise on FARA compliance. “It doesn’t really matter who pays. Your foreign principal under FARA has to be the person for whom you’re an agent. The whole point of the law is to disclose who you’re really working for.”

Yet the whole purpose of an offshore shell company is to obscure the true interests behind it. “That’s why you use shell companies,” says Jack Blum, a Washington lawyer with expertise in international tax avoidance. “For secrecy.” Indeed, it seems unlikely that Fidetzis, who has no apparent Albanian interests, was financing Dorelita’s expensive lobbying campaign himself. And he was possibly acting on behalf of another party. So the question remains: Who was funding pro-LSI lobbying in the United States, and what was the objective behind this influence campaign? Peeling back the layers on Dorelita does little to clear this up—but the story of this shell company does reveal much about how the murky foreign influence game is played in Washington.

Additional reporting by Achilleas Zavallis from Cyprus

Image credits: Bill Clark/Roll Call/AP; Imago/ZUMA; dkfielding/Getty