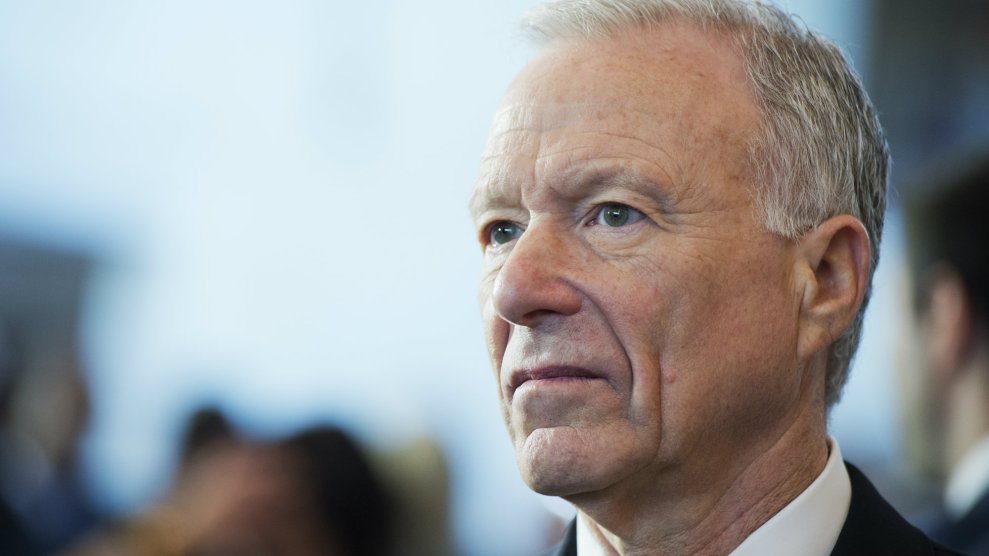

Scooter Libby outside federal court after his 2007 conviction.Gerald Herbert/AP

We should have seen this coming.

More than a decade ago, I. Lewis Libby—a.k.a. Scooter—was convicted in federal court of lying to a grand jury and to the FBI and of obstructing justice. Libby had been chief of staff to Vice President Dick Cheney and one of the leading architects of the US invasion of Iraq, which the Bush-Cheney administration sold to the public with false and hyperbolic claims regarding Saddam Hussein’s (nonexistent) weapons of mass destruction programs and his (nonexistent) alliance with Al Qaeda. President Donald Trump pardoned Libby on Friday.

There was no pressing reason for Trump to revive this matter. “I don’t know Mr. Libby, but for years I have heard that he has been treated unfairly,” the president said in a statement. That was hardly a rousing explanation. But there is this: Libby was prosecuted by US Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald, who had been appointed as special counsel in 2003 by a deputy attorney general named…James Comey. Whatever Trump’s intent, the Libby pardon was a raised middle-finger to the fellow who has just compared Trump to a Mafia chieftain. It also sent a troubling signal that this president is not offended by those who stonewall the FBI and special counsels. Get the picture?

Libby has long been a martyr for neocons and conservatives who have claimed he was the innocent victim of a political prosecution. (What a coincidence.) But his case was serious, for the main issue was whether he could get away with lying to federal investigators in order to protect his boss, the vice president. This episode is highly relevant today.

As it happens, years before Michael Isikoff and I wrote our current book, Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin’s War on America and the Election of Donald Trump, we wrote Hubris: The Inside Story of Spin, Scandal, and the Selling of the Iraq War, an account of how the Bush-Cheney gang greased the way to the Iraq War in 2003 with misrepresentations and lies. The book also covered the Libby case and (in the paperback edition) his 2007 trial in a federal district courtroom in Washington, DC.

Libby’s offenses were related to an investigation of the leaking of the identity of Valerie Plame, a CIA officer married to former Ambassador Joseph Wilson. A few months after the 2003 Iraq invasion, Wilson asserted publicly that prior to the war, the Bush White House had information undercutting its own assertions that Saddam possessed WMDs. Wilson had been dispatched the previous year by the CIA on a private mission to the African nation of Niger to check out one of the administration’s claims—that Saddam had secretly obtained weapons-grade yellowcake uranium there. He had found nothing to substantiate this charge. When he blew the whistle on the Bush-Cheney administration—revealing in a July 6, 2003, New York Times op-ed that the yellowcake claim was bunk and questioning both the justification for the invasion and the integrity of the Bush-Cheney crew—the White House, especially Cheney’s office, went ballistic. It immediately tried to discredit and smear Wilson. As part of that campaign—which had begun even before the op-ed was published—the White House collected information on Wilson, including the fact that his wife worked at the CIA and had been involved in the plan to send Wilson to Niger.

With the operation to undermine Wilson underway, a newspaper column by conservative pundit Bob Novak revealed that Wilson’s wife was a CIA operative and named her. Novak cited as his sources two unidentified “senior administration officials.” It is a crime for federal government officials to out an undercover CIA official. (At the time, I was the first journalist to report that the Plame leak was a possible violation of federal law.) And eventually this leak became the subject of an FBI investigation that evolved into the special counsel probe run by Fitzgerald.

As Isikoff and I would later reveal in Hubris, Novak’s first source for the Plame information was Richard Armitage, the deputy secretary of state, who was not part of the Bush-Cheney administration’s get-Wilson campaign. But the second source was Karl Rove, the chief strategist for the Bush White House, who was eager to undermine Wilson’s account. Neither Armitage nor Rove was ever prosecuted for leaking this information. (Such cases are tough to bring, given the wording of the relevant law.)

Libby, who also spread information about Plame’s CIA identity to reporters, was not prosecuted for the leak. He was nabbed instead for trying to mount a cover-up.

When FBI agents came knocking, Libby told the bureau that he had learned about Wilson’s wife from Tim Russert of NBC News. He neglected to mention that in the weeks before his conversation with Russert, he had been part of the operation conducted by Cheney’s office to gather information on Wilson and Plame—and that Cheney himself had told Libby that Plame worked in the counterproliferation division of the CIA. Libby told the investigators that after his discussion with Russert, he had told another reporter (Matt Cooper, then with Time magazine) that he had heard from other reporters that Plame worked at the CIA but that he did not know if that was true. In other words, Libby claimed he had simply picked up and passed along scuttlebutt—information he had not confirmed. If this description was accurate, it would not be a violation of law. And with this account, Libby was keeping Cheney out of the picture and far apart from any plot to assail an administration critic.

When Libby was called before the grand jury, he was confronted with documents showing that Cheney had indeed told him weeks before the Wilson op-ed that Plame worked for the CIA. So Libby came up with something of a new tale. He claimed that he had forgotten that Cheney had informed him about Plame and that he had learned this fact anew when Russert shared the information with him after the Wilson op-ed was published. It was a convoluted explanation—but one that supported Libby’s initial contention that he believed he had first heard about Plame from Russert.

Libby went on trial in early 2007. In the courtroom, Fitzgerald noted that Libby’s defense was implausible. He had completely forgotten that Cheney had told him Plame was a CIA officer and thought he had heard it from Russert for the first time? A parade of witnesses from the Bush-Cheney administration testified that they, too, had talked about Plame and her CIA connection with Libby prior to the conversation he had with Russert. (Onetime White House press secretary Ari Fleischer only cooperated with Fitzgerald’s investigation once he was granted immunity.)

For his part, Russert testified that it was an “impossibility” for him to have told Libby anything about Wilson’s wife, for he knew nothing of her CIA tie until Novak’s column appeared. In his closing argument, Fitzgerald declared, “There is a cloud on the vice president…That cloud remains because this defendant obstructed justice.” This was his way of saying that Libby had lied to cover for Cheney. Libby “stole the truth from the judicial system,” Fitzgerald told the jury.

The jury found Libby guilty on four counts. Afterward, on the courthouse steps, Fitzgerald declared that Libby, with his lies, had attempted to block the leak investigation from reaching Cheney. “Sometimes when people tell the truth, clouds disappear,” he added. “Sometimes they don’t.”

The record was clear. Libby concocted a phony story to defend the false statements he had made to FBI agents to thwart their investigation into the Bush White House’s role in the Plame leak. Yet with his conviction, he immediately became a martyr for conservatives defending the Iraq War. (Two of his champions since then have been DC lawyers Joseph diGenova and Victoria Toensing, the pro-Trump, conspiracy-mongering, Fox News-friendly husband-wife couple who recently almost joined the president’s legal team.) Libby was sentenced to 30 months in prison and a $250,000 fine. But the neocon crowd pushed President George W. Bush to pardon their hero, who had taken a big fall for Cheney. Bush wouldn’t do that, but he did commute Libby’s sentence, removing the prison term. That wasn’t enough for Cheney. Toward the end of the Bush presidency, he urged Bush to grant Libby a full pardon. Bush refused, causing a rift between himself and his No. 2.

The Libby lobby has persisted, for years insisting he had been railroaded and deserved a pardon. And for some reason, just as Trump is being pummeled by Comey—and just as the investigations surrounding the president are intensifying—Trump responded to that call.

From his statement, it is clear that Trump was not familiar with the details of the slam-dunk case against Libby. So it seems that what appealed to Trump was the symbolic nature of this action: a senior administration official had lied to block an investigation of wrongdoing within that administration—and was punished for doing so. But with this pardon, Trump has sent the message that he does not find that sort of dishonest conduct reprehensible. In Trump’s world, this pardon was not an act of justice. It was a wink.