On the eighth anniversary of the worst American mine disaster in half a century, Don Blankenship was camped out at a diner in Elizabeth, West Virginia, explaining to an audience of two why his recently completed stint in federal prison made him more appealing to voters.

The trip to B-Bopp, a ’40s-themed joint about the length of a Mack truck, had been advertised as a chance to throw questions at the man whose campaign for US Senate has thrown Republican operatives into crisis mode. But only a pair of white-haired men had stuck around for lunch with Blankenship and his entourage. “We was told we come down here, we’re gonna eat,” said one of them, a bespectacled activist with a Trump hat and a prospector beard.

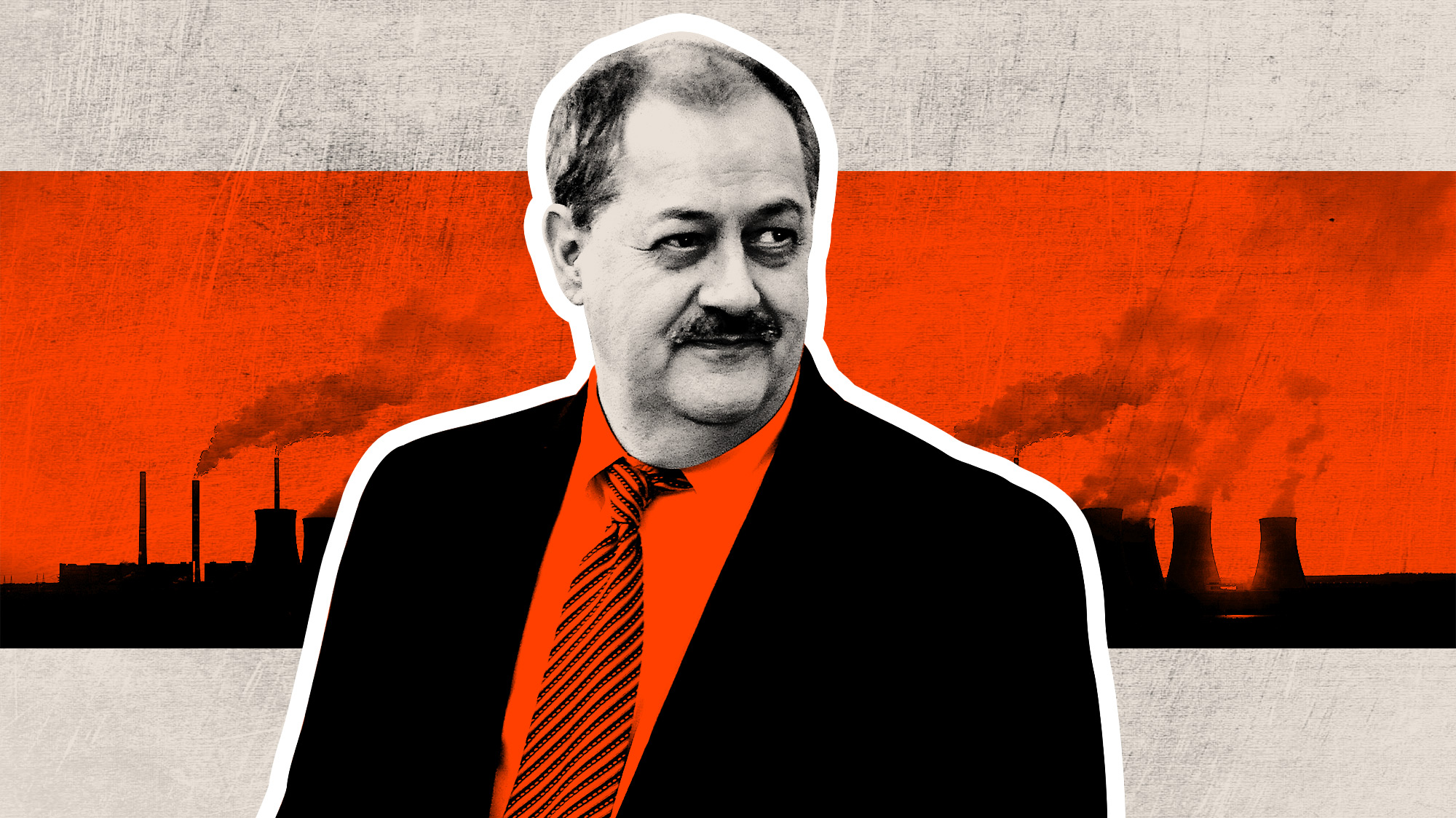

The 68-year-old Blankenship is a large man with thinning hair, a double-wide chin, and a thick brown mustache. During his 18 years as CEO of the Appalachian coal giant Massey Energy, he cultivated a reputation as a domineering taskmaster whom subordinates crossed at their peril—a boss who bragged of having been shot at by his own employees, a millionaire who allegedly ripped a coat rack out of the wall to prove a point to his housekeeper. But Blankenship is so soft-spoken in person it sometimes sounds as if he is talking to his shirt. He struggles at small talk. He’d rather discuss his ads.

“As I say in one of my commercials, it should be easy to choose between me and the others,” he said, as he waited on his egg sandwich, “because the enemies I have are the very enemies of West Virginia—Obama and Hillary.”

Two years ago, Blankenship was sentenced to a year in prison for conspiring to violate federal mine safety laws in the lead up to the April 5, 2010, explosion at the Massey-owned Upper Big Branch (UBB) mine. Twenty-nine miners died in the blast. Although he was never charged in connection with the explosion itself, four subsequent investigations reached the same conclusion: Massey’s emphasis on profits over safety had created a perfect storm of hazards that made the disaster possible. Prosecutors had aimed to send Blankenship to prison for 30 years on a handful of charges, the most serious of which was making false statements to the Securities and Exchange Commission about Massey’s safety record (a felony). After he was found guilty on a single misdemeanor charge, the judge handed down the statutory maximum. Blankenship went from being a merely polarizing figure in the state to a pariah.

But that was then. Now, Blankenship isn’t running from his conviction—he’s largely running on it.

RELATED: The Epic Rise and Fall of America’s Most Notorious Coal Baron

“It’s probably the most helpful thing in the campaign—it’s amazing. When the truth comes out about what they did,” he said, referring to the Obama administration, “it’ll make the Russian probe look benign.”

In the Trump era, as the president and his allies assail the integrity of the Justice Department and warn of a shadowy “deep state,” Blankenship’s comeback is tailor-made for the moment. He pitches himself as a “political prisoner,” a sort of Nelson Mandela of the war on coal. He holds the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), not his former company, responsible for the deaths of his miners, and he has said that the government’s “cover-up” of what happened at Upper Big Branch is “far worse than Benghazi.” Flush with an $86 million golden parachute from Massey, he’s spent freely on West Virginia’s airwaves to make sure everyone knows it.

Blankenship’s candidacy has shaken up one of 2018’s most-watched Senate races. Tempting fate, a group of Democrats that includes the former US attorney who led Blankenship’s prosecution formed a super-PAC to attack his rivals, in the hopes of pushing him into the general election against Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin. Republican Party leaders, fearful of Roy Moore redux in a state President Donald Trump carried by more than 40 points, have scrambled the jets. As Blankenship was diving into a slice of chocolate cake at B-Bopp, Trump was on his way to a photo op in Greenbrier County with the other Republican contenders in the race, Rep. Evan Jenkins and Attorney General Patrick Morrisey. It was not hard to detect a hint of desperation.

With the primary—and the end of Blankenship’s probation—days away, he has crept uncomfortably close to Jenkins and Morrisey. A few years ago such a redemption tour would have been unfathomable. But Blankenship is telling a story that, for more than a year, Trump has primed Republican voters to hear.

At 7:05 a.m. on May 10, 2017, the day he was released from a halfway house in Phoenix, Blankenship logged on to Twitter and challenged Manchin to a debate on UBB. Five days later, he wrote a letter to the president asking him to revisit the case.

When he announced later that year that he was moving back from Las Vegas—his official residence since 2009—to run for Senate, there was no gauzy video playing up his humble start, raised by a single mother in a camper beside a gas station in a broken-down town called Delorme. Instead, Blankenship bought an overhead projector and, in a drawl barely rising above a monotone, he walked voters and reporters through a series of slides making the case for his innocence.

The story that Blankenship has spent more than $2 million to present to West Virginians this year is not new. He has been telling it, in every conceivable format, since the aftermath of the explosion—in a documentary he produced, starred in, and paid to air on local TV stations; in a speech at the National Press Club; in a 67-page booklet he mailed to a quarter of a million people from prison.

His version of events starts off simply enough: The disaster was in fact caused by an inundation of natural gas that rose through a crack in the floor—an act of God—and was allowed to collect in the mine by a ventilation plan foisted upon UBB’s operators by MSHA bureaucrats.

Blankenship contends he was scapegoated for the disaster because of a series of personal vendettas—because he had called out the Obama administration’s regulatory excess; because he had clashed with then-Gov. Manchin (who said that Blankenship had “blood on his hands” after the explosion); and because MSHA’s leadership had close connections to the union Blankenship crushed during his rise to power.

What’s new, post prison, in Blankenship’s narrative, is the distinctly Trumpian gloss. “Tyrant” Obama conspired with Manchin and MSHA to cover up the truth, one ad begins, and packed him off to prison. A prison, Blankenship says, filled with thousands of undocumented felons. Blankenship, who once referred to the first black president as “Hussein Obama,” has made his case in ads filled with racial fog horns. One spot included photos of the African American judge, Irene Berger, who oversaw his trial (and is referred to as “the Obama judge”) and three black justices from the 4th Circuit who rejected his appeal, along with Barack Obama. Manchin is the only white face we see. Sometimes Michelle Obama makes an appearance in the ads. Sometimes we get Hillary Clinton. You end up with a campaign that looks like this:

Or this:

Blankenship’s spots appear low budget and poor quality, but maybe that’s the point. Watch enough of them and UBB starts to lose focus. It stops being something that happened to 29 mine workers, and it becomes something that happened to Don Blankenship.

Here’s what actually happened, according to the four investigations carried out after the blast. The explosion that ripped through UBB at 3:02 p.m. on April 5, 2010, was over in a matter of minutes. The first rescue teams were underground within an hour, but it would take four days to search the entire mine and another four to recover all 29 bodies. On the morning of April 13, a human chain brought the last of the men up from the mine and draped them in American flags. Not long after that, then-Gov. Manchin placed a call to Davitt McAteer.

Jowly and white-haired, with a bushy mustache, McAteer came from a family of miners but had never worked in one himself. He was in law school in 1968 when the Farmington mine blew up near his hometown of Fairmont, West Virginia, killing 78 men. McAteer decided on a career as a safety consultant for the mine workers union; he was later tapped by Bill Clinton to head MSHA.

McAteer had worked for Manchin before. In 2006 he had conducted an independent investigation at Aracoma, a Massey-owned mine where two workers died after a fire broke out in an underground storage unit; a few months later, he probed the explosion that killed 12 workers at the Sago mine, owned by a subsidiary of the International Coal Group. MSHA’s Aracoma report found that the sprinkler system and a smoke detector hadn’t worked, that the emergency exits weren’t marked, and that a carbon monoxide detector hadn’t been installed. One miner testified to state investigators that he had never once participated in a fire drill.

A few weeks after he got the assignment to investigate UBB, McAteer and a small team walked into the mine. UBB was what is known as a longwall mine, with a massive shearer, weighing about 90 tons, working slowly across the face of a coal seam 1,000 feet wide. This type of mining is enormously expensive. The capital investment runs into the tens of millions of dollars. But a company can make that back and much more—as long as production on the longwall doesn’t stop.

Shearers cut cleanly into coal but can create sparks if they hit rock, so longwall mines are required to have spray systems that produce a steady mist to prevent conflagrations. According to McAteer’s report, the spray system at UBB didn’t work. Massey saved money by drawing water from a nearby river, McAteer told me, and “there were a number of sprays that had become clogged with silt.” Both his and MSHA’s investigations found that the problem had been a recurring one, and that the mine’s operators were aware of the problems river water presented.

McAteer’s inquiry and three other investigations—from MSHA; the United Mine Workers of America; and the West Virginia Office of Miners’ Health, Safety, and Training—reached largely the same conclusion. A spark ignited a pocket of methane that had built up because of poor ventilation. (One reason for the poor airflow on April 5th, according to McAteer’s report, was that a portion of the mine had flooded because the pumps had failed; this was also a recurring problem—MSHA inspection records showed miners sometimes waded through four feet of water near the longwall.)

RELATED: “I Could Krushchev You”: 9 Shocking Allegations From the Don Blankenship Indictment

Blankenship’s theory that the explosion was fueled by an unexpected inundation of natural gas through a crack in the floor was actually one that investigators explored. But all four investigations rejected this theory. A natural gas explosion such as the one Blankenship alleged would have left a much different forensic footprint than the one investigators found, McAteer’s report explained. But “even if the cause of the explosion had been found to be an infusion of natural gas or methane into the UBB mine atmosphere,” the report went on, these were things the mine was supposed to be prepared to handle—there had been a small methane explosion at the mine before, and UBB had previously been evacuated because of a methane problem.

Blankenship has repeatedly denied any wrongdoing at UBB. He claims instead that Massey had implemented a ventilation plan forced on it by MSHA. But the record McAteer examined showed no evidence for that. According to his findings, UBB often made changes without consulting MSHA and was cited for tinkering with the ventilation while miners were underground—a dangerous and prohibited practice. The mine was frequently in violation of its own patchwork ventilation plan, which relied on a cheaper system of air-lock doors that operators are supposed to avoid using whenever possible. UBB had no on-site ventilation engineer until just a few months before the disaster, and portions of the mine had been evacuated twice in the years preceding the explosion for having air blowing the wrong way—a catastrophic failure.

The four separate investigations agreed that it was high levels of coal dust that turned the small initial methane explosion into a major explosion that stretched for miles. Coal dust is highly combustible, so mines typically deploy mechanical dusters to coat the walls, ceilings, and equipment with pulverized rock, as a form of fireproofing. The rock dusters worked poorly at UBB, the investigators found; in some places miners had been applying the mixture by hand. The company had been cited for excessive amounts of coal dust repeatedly, and not just in a few problem areas—it was all over the mine. According to McAteer’s report, of the 24 deceased miners at UBB whose lung tissue could be analyzed, 71 percent showed signs of black lung.

Blankenship did some things right. Massey miners were among the first to wear reflector stripes on their work clothes to avoid accidents. He also pushed for mechanical devices used in mines to have proximity detection sensors—like the sort used on some cars—to avoid collisions with miners. But the numbers, and the inspection records, told the bigger story: an American University analysis found that Massey mines were 17 times deadlier than those of the company’s biggest competitor in the decade leading up to UBB. In the days that followed the disaster, miners and the family members of victims described a workplace where safety concerns were shunted aside.

(Alpha Natural Resources, which acquired Massey in 2011, eventually reached a $210 million settlement with the federal government in response to UBB. The settlement included $46 million for the families of the 29 miners and $35 million in penalties for mine-safety violations. “While we can’t ever forget what happened on April 5, 2010, there is a time to take the hard lessons and effect positive change for the industry,” a spokesman for the company said at the time. The company did not respond to questions about Blankenship’s theory of the cause of the disaster.)

Why was Massey running coal when the spray system didn’t work? How could a mine rack up repeat violations for the same problem without ever fixing it? These aren’t questions Blankenship engages with in his ads, but the case built by federal prosecutors offered an answer—it was because Blankenship considered safety violations a “cost of doing business,” as US attorney Booth Goodwin put it during his closing argument in the coal mogul’s trial.

After the 2006 fire at Aracoma, state and federal investigations detailed a culture at Massey that was hostile to basic safety measures. “If any of you have been asked by your group presidents, your supervisors, engineers or anyone else to do anything other than run coal (i.e.—build [ventilation] overcasts, do construction jobs, or whatever), you need to ignore them and run coal,” Blankenship wrote in one memo. The story at UBB was the same. “We’ll worry about ventilation or other issues at an appropriate time,” Blankenship wrote in response to complaints about the mine’s airflow—a memo that was quoted in his 2014 indictment. He called subordinates who diverted miners from the longwall for safety work “ridiculous.” Over and over, at his trial, in hearings before Congress, and in interviews with McAteer, workers testified about the pressure they were under to move coal.

(Blankenship offered no response when I asked him about UBB in person, and his campaign did not respond to a request for comment; his lawyer previously told me, “Donald Blankenship is entirely innocent.”)

The irony of Blankenship’s campaign is that he’s sort of right to lay blame at MSHA’s feet. Both McAteer and the United Mine Workers of America (as well as MSHA’s internal review) agree that MSHA should have been aware of systemic safety failures at the mine in the run-up to the explosion. It had the power to shut the mine down until those failures could be addressed. But MSHA lacked the will, or maybe the teeth, to make the changes that mattered. If the deep state really did have it out for Blankenship, UBB might never have happened at all.

The Trump administration, which has made rolling back regulations and reviving the coal industry a key part of its agenda, has not helped the problem. Trump picked a former coal CEO to run MSHA whose company twice received a “pattern of violation” from the agency for repeatedly violating safety standards. Under his leadership, MSHA amended an Obama-era rule that mandates pre-shift safety inspections of every mine—something UBB was cited for repeatedly. Trump’s Commerce Secretary, Wilbur Ross, owned the Sago mine that blew up. Meanwhile, Republicans on the House Financial Services Committee recently voted to scrap the law that requires publicly traded companies to disclose safety information—the very law, Blankenship explains in so many ads, that nearly put him away for the rest of his life.

On his way into the diner, Blankenship stopped to shake hands with a man in a leather jacket and baseball cap named John Griffin, who told him he couldn’t imagine life without a dump truck, a pickup truck, and a Harley. Blankenship offered a fourth necessity—guns—and a rare laugh. “You’re saying everything I want to hear in your commercials,” Griffin said, turning serious. His trucking business works with coal companies, and he lives in fear of getting slapped with a big fine by MSHA.

“I believe he’s innocent,” Griffin told me, but he was waiting to see all the candidates later that night, at the Wood County GOP Reagan Day Dinner up the road in Parkersburg, to make up his mind. I never had the chance to follow up with Griffin after the county GOP chair, Rob Cornelius, a longtime Blankenship adviser, spotted me at the dinner that evening.

“You guys suck,” he said. “You’re fake news. You’re a bunch of dirty hippies. So yeah, I need you to go. Thank you!”

Cornelius had once been briefly ousted from his chairmanship for threatening a process server with a baseball bat, so I did leave. But Blankenship’s performance that night—as recounted by the next morning’s Parkersburg News and Sentinel—was characteristic of the way he’s approached the entire campaign. There was no congeniality. He went hard after Jenkins and Morrisey, hammering the former for having recently been a Democrat (which is true) and the latter for having taken big bucks from the prescription drug companies he was supposed to regulate (which is also true). Neither of them, Blankenship said, would even be in the primary if he hadn’t paved the way for them. There’s some truth to that too.

In the decade leading up to Upper Big Branch, Blankenship was the state Republican Party’s largest donor. He spent millions beating back ballot initiatives and attempting to build a GOP bench in the state legislature. If he wins the primary, it’ll be because he stuck to a playbook that worked in the past. “Don would be the first to admit that he hasn’t done a lot to cultivate the image of himself as warm and friendly,” his lawyer once said. Blankenship’s style is to go on offense.

When, in the early 2000s, Massey found itself facing a $50 million civil judgment for strong-arming a competitor out of business, Blankenship spent $3 million to unseat a state Supreme Court justice he believed would rule against Massey. His consultants concocted an alternative story to sell to voters—that the incumbent was soft on child predators. One ad featured an empty swing set. They called their effort “And for the Sake of the Kids.”

The two front-runners in the Senate primary have been more reluctant to unleash the kind of attacks against Blankenship that he’s let lose on them. In fact, they’ve hardly mentioned him at all. That paralysis is perhaps rooted in recent history: Republicans are wary of repeating what happened last year in Alabama, where Roy Moore won his primary by casting the national Republicans who flogged his record—he had twice been removed from the state Supreme Court for defying court orders—as Washington “swamp” creatures. Another thing Blankenship’s rivals seem to have recognized? Attacking someone for legal woes isn’t as simple as it used to be, now that the president spends his mornings assailing his own Justice Department.

Instead, the work of taking on Blankenship has fallen to an outside group connected to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell—the innocuous-sounding Mountain Families PAC. The group’s first ad, released in mid-April, refers to the former coal baron as a “convicted criminal” but focuses largely on Massey’s environmental record—the company injected 1.4 billion gallons of coal waste into underground storage caverns in Mingo County leading to a $35 million settlement. The second, released this week, zeroed in on Upper Big Branch. “Don Blankenship was about the money,” a narrator says. “West Virginia families paid the price.”

Blankenship responded to the PAC’s attack ad with one of his own. He released a video promising to “ditch ‘Cocaine Mitch’”—a weird reference to a 2014 incident in which a ship owned by the senator’s in-laws was caught carrying about 90 pounds of cocaine—and ended with a familiar send-off. “When you vote for me,” he said, “you’re voting for the sake of the kids.”

“Cocaine Mitch” isn’t exactly subtle, but nothing about Blankenship’s appeal for Trump voters is. West Virginia was Trump’s second-best state in 2016, and Blankenship is trying to convince voters he’s cut from the same loose-fitting cloth, and not just because they’re both, in his view, innocent victims of a deep state conspiracy. He’s a powerful businessman who’s made the right kind of enemies; a political donor who can’t be bought; and above all, a savior for the forgotten man who will bring the coal jobs back, build the wall, and kick China in the teeth. A vote for Don is a vote for Don:

The attacks on Blankenship might be working; he’s dropped off slightly since the McConnell-connected PAC targeted him in early April. But the conditions that enabled his comeback campaign—that have trained conservatives to fix their wrath on the systems that check bad behavior rather than the men prosecuted for it—are shaking up other campaigns too. Former New York Rep. Michael Grimm, who spent eight months in jail for tax fraud, and former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, held in contempt of court (and subsequently pardoned by President Trump), are both hoping this same paranoia translates into votes. Trump’s re-election campaign will be founded on it. There are consequences to teaching an entire political party that it’s the speed limits that cause accidents. If Upper Big Branch had happened today, it’s reasonable to wonder whether anything would have happened to Blankenship at all.

While the Republicans were scrambling to stave off Blankenship, Manchin kicked off his own reelection campaign last month with a 30-second television ad about the 1968 Farmington explosion. Manchin, who grew up in the town, pointed at the names on the black, granite memorial and spoke directly to the camera. “I lost an uncle, I lost a neighbor, I lost guys I played ball with,” he said. “This is real for me.” It was not hard to decipher a message, or who it might be targeting.

In speeches and in interviews during the campaign, Blankenship has made an unusual argument—that if it were up to the southern counties of West Virginia, where his miners lived and worked, he would win in a landslide. This fits into the narrative he has long built for himself, as the savior of coal country, a man with enough guts to open up the mines and bring the jobs back. But in the run-up to his trial, Blankenship’s own attorneys argued their client was so hated in coal country he could never get a fair trial. Their filing cited polling numbers, along with a long list of comments that had come from family members of UBB victims:

“He’s a murderer is what he is…He don’t have no remorse.”

“He has no heart. He has no soul.”

“I just can’t stand to look at him.”

“The man is the Devil.”

“He will pay. Whether it’s in this life or the life to come, he’ll pay for what he’s done.”

Blankenship is betting that those sentiments have softened since he was sentenced. And perhaps they might have if he’d stayed in Las Vegas or suggested, just once, that Massey bore some responsibility for what happened. But in publicly dismissing the official story of the disaster to further his own ambitions—in roping 29 families into his own personal story of redemption and casting himself as a victim of an explosion he walked away from $86 million richer—Blankenship is poking at wounds that never fully healed.

“I talked to a guy the other day; he said he should have drowned him as a child,” Richard Ojeda, a Democratic state senator and candidate for Congress, said of Blankenship. People don’t say that about Evan Jenkins.

Early in the morning on April 5, before meeting Blankenship at B-Bopp, I made my way down a pocked and scarred mountain road to Whitesville, where a memorial to the miners was set up at the rear entrance to UBB. Now and then, convoys of coal trucks punctuated the early morning calm. Around 9 a.m., a florist stopped by and placed an arrangement of white carnations in the center of the memorial. A few minutes later, a white SUV pulled onto the gravel entrance and out stepped a man named Mon Lynch. He walked slowly up to the memorial and paused in front of a photo of his father.

William Roosevelt Lynch coached high school football and basketball on his days off at the mine. He had had started off as a roof bolter when Mon was a child, responsible for drilling long steel rods into the ceiling of the mine to prevent cave-ins. He eventually settled in as a shuttle car operator (known in industry parlance as the “buggy”), who shepherds materials around the mine. Mon had worked at UBB as well. After the explosion, he called it quits. Now he sits behind a desk at an insurance company. Lynch laughed when he told me he worries about carpal tunnel. But his smile faded when the subject turned to Blankenship.

“I just don’t understand how you do that little bit of time and then you get out and then you run for office—I don’t understand it,” he said. “There should be some kind of legal ramifications. You go to prison, you can’t do stuff like that. A lot of people can’t vote after they get out of prison, but you can run for office? I don’t understand.”

His mother was waiting in the passenger seat, and after a few more minutes Lynch got back in the car. When they were gone, I took a look at the note poking out of the flowers: “We will never forget you! Your friend, Joe Manchin.”

Image credit: Chris Tilley/AP; kamilpetran/Getty