Police officer giving sobriety test to young man to see if he is driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol. kali9/iStock/Getty Images Plus

On a Thursday morning in late February, Utah state Sen. Jim Dabakis (D) had breakfast, downed a couple of mimosas, and caught a ride to the state capitol, where he introduced a bill to to delay the implementation of the nation’s strictest drunk-driving law. Passed in March 2017, the measure would lower the legal blood alcohol content (BAC) limit for drivers from .08 to .05 percent.

On the capitol floor, Dabakis argued that the law would only depress tourism in a state already known for its weirdly strict alcohol laws. He scoffed at the idea that someone with a .05 BAC would be too impaired to drive. In fact, he disclosed to his mostly Mormon colleagues, his two-mimosa breakfast led him to blow a .05 on a breathalyzer test shortly before entering the building. “I feel perfectly fine,” he said.

His colleagues were unpersuaded, and on December 30 this year, Utah will officially become the first state in the country to lower the legal BAC threshold for drunk driving to .05 percent. Other states are considering following suit. Legislators in Delaware introduced a bill to do so in March. Lawmakers in New York, Hawaii, and Washington have also introduced bills. But Utah, the first state to adopt the .08 BAC limit, in 1983—back when .10 percent was the legal limit in most states—may continue to be an outlier for a long time as the industry pushes back and some of the most influential advocates against drunk driving sit on the sidelines. Outside of Utah, not a single bill aiming to lower the BAC limit has gotten a hearing.

Michael Scippa, a spokesman for the nonprofit advocacy group Alcohol Justice—one of the only groups working on the BAC issue—acknowledges the challenges ahead. “We’re in this for the long haul,” he says. “It’s a 10-year campaign.”

The National Transportation Safety Board first called for lowering the BAC limit to .05 in 2013, based on substantial evidence from labs and road-track tests showing that impairment from alcohol starts with the very first drink. (Roughly speaking, a 160-pound man would hit a .05 BAC by consuming two drinks in an hour.) The research showed that virtually all drivers are impaired at a BAC of .05, and a driver with a BAC between .05 and .079 has at least seven times the risk of dying in a single-vehicle crash than someone who hasn’t had a drink. (That’s why the BAC limit for commercial drivers is already .04 percent.)

In January, the prestigious National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) echoed those findings in a new report that sought to reinvigorate stalled efforts to combat drunk driving. The NASEM estimated that if every state reduced the BAC limit to .05, drunk driving deaths would fall about 11 percent, saving nearly 1,800 lives a year.

In many ways, the battle against drunk driving has been a victim of its own success. Led by the nonprofit group Mothers Against Drunk Driving, states started passing a number of laws targeting drunk driving in the early 1980s, including measures raising the legal drinking age to 21 and lowering the BAC limit from .10 percent to .08. Congress eventually reinforced those efforts by threatening to withhold federal highway funding from recalcitrant states that refused to make the changes. Alcohol-related driving deaths fell by almost 40 percent between 1982 and 2015.

But for the past seven years, the share of traffic deaths caused by alcohol hasn’t budged from around 30 percent, and there’s some evidence that it’s starting to creep back up. Nearly 10,500 people were killed in drunk-driving accidents in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available, an increase of about 1.7 percent over the previous year. Those accidents claim a lot of innocent victims. Nearly 40 percent of the people killed in drunk driving accidents are not the drunk driver. They’re passengers, pedestrians, cyclists, and sober drivers. The wreckage is expensive, too: The NASEM estimates that alcohol-impaired driving costs the country more than $120 billion a year.

The problem is not intractable. The .05 BAC limit is used by most European countries, including heavy-drinking France and Germany, where the percentage of traffic fatalities that involve alcohol is much lower than in the United States, even though people there consume more alcohol per capita. Steven Teutsch, chair of the NASEM committee on impaired driving, says, “The BAC is one of the more potent things that can be done to reduce alcohol-related fatalities.”

Teutsch says some opponents claim that lowering the BAC won’t save many lives because most fatal accidents occur among drivers whose BAC is well above .08. But Teutsch says evidence from other countries shows that after switching to the .05 BAC limit, the number of drunk-driving fatalities falls across the board as fewer people choose to drive after drinking. In other words, there are fewer people crashing their cars at a BAC of .07 or .08, but there are also fewer driving and crashing at more severe levels of inebriation. Researchers believe the law has a strong deterrent effect and is an important step in changing social norms. “It really is about changing the behaviors,” Teutsch says.

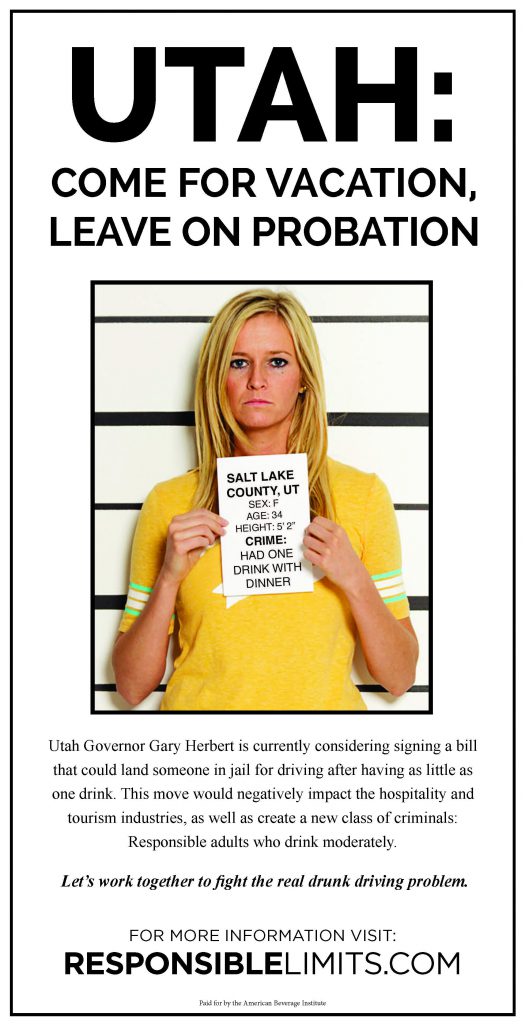

Utah, for its part, had already done most of the other things recommended by the NASEM to combat drunk driving, such as raising alcohol taxes and limiting alcohol availability. (For example, there are no drive-through liquor stores in Utah.) It has one of the lowest rates of drunk driving fatalities in the country. But Rep. Norm Thurston, a conservative Republican state legislator with a Ph.D. in economics from Princeton University, found the data on the benefits of a .05 BAC limit convincing. He introduced a bill in 2017. The backlash from the industry was immediate and fierce. The American Beverage Institute (ABI), a Washington, DC, nonprofit that represents the bar and restaurant industry, launched a campaign proclaiming, “Utah: Come for vacation, leave on probation.”

The group took out full-page ads in USA Today and in newspapers in Nevada and Idaho targeting potential tourists to Utah and suggesting that having one drink with dinner would turn a woman into a criminal once she got behind the wheel.

The ABI argued that the state should focus on the real drunk drivers, those whose BAC is well over .08. A .05 BAC limit “distracts law enforcement from dangerous high-BAC and repeat drunk driving offenders—the ones responsible for nearly 70 percent of alcohol-related traffic fatalities,” wrote ABI managing director Sarah Longwell in an op-ed in the Washington Examiner. “When you funnel limited traffic safety funds into targeting those who enjoyed a drink with dinner, that comes at the expense of catching someone dangerously impaired at 0.18, the average BAC of a drunk driver involved in a fatal crash. That’s a dire misallocation of resources.”

Opponents even brought in Candy Lightner, one of the founders of MADD who went on to work as an alcohol industry lobbyist in the 1990s. She penned an op-ed in the Salt Lake Tribune with a headline calling the .05 BAC limit an “unhelpful distraction.”

Proponents of the BAC change don’t understand why the industry is digging in its heels. “To be honest, I don’t know what they’re afraid of, because there’s absolutely no evidence that it reduces alcohol consumption,” says James Fell, a traffic safety researcher who spent 30 years at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and is now at NORC at the University of Chicago, a nonpartisan independent research institute. He co-authored a 2017 scientific paper published in the journal Alcoholism that evaluated studies on alcohol consumption after BAC changes across the globe and found little change. “Scotland went to .05 a few years ago, and there hasn’t been any mass closing of bars or restaurants,” he notes.

In Utah, Thurston found broad support for his bill. The Mormon church’s backing was not a surprise, but other supporters included the state PTA; the Sutherland Institute, a local right-wing think tank better known for fighting gay marriage; the state highway patrol office; and the Utah chapter of the Eagle Forum, a family values group founded by the late conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly. “The only real resistance has come from people who make a living from selling alcohol,” says Thurston. Still, he welcomed the publicity stirred up by the ABI. “I think they’re being ridiculous and unfair,” he says. “But the reality is that every time they speak, we get free media coverage, which helps save lives.”

He says the law has cost the state nothing to implement and will likely end up saving taxpayers money as traffic accidents decline.

But other states aren’t exactly racing to lower their BAC limits. While a handful have introduced bills, not one has made it to a hearing. During the movement to change the BAC from .10 to .08 percent, there were dozens of national groups and companies pushing the issue at both the state and federal levels, including the American Medical Association, the American Automobile Association, the insurance industry, and carmakers Ford and General Motors. And there were strong proponents in Congress, notably the late Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.). Today, there are virtually no advocacy groups* working on the .05 BAC limit nationally, nor is there a champion in Congress. Notably absent, too, is MADD, which rallied the families of drunk-driving victims in a high-profile campaign to change the BAC from .10 to .08 but declined to support Utah’s change to .05.

MADD is sitting this one out, says J.T. Griffin, the group’s chief government affairs officer. Instead, the group is focusing on pushing more states to force DWI offenders to install ignition interlocks, which breathalyze drivers and prevent them from starting vehicles if they have been drinking.* “States went kicking and screaming to .08,” he says, recalling the political battle that lasted more than 20 years. The last state, Minnesota, didn’t adopt the .08 BAC limit until 2005. “From MADD’s perspective, there’s a lot of challenges of moving from .08 to .05.”

The lack of any national organized effort for a .05 BAC limit has frustrated some drunk-driving victims. In 2016, Marcus Kowal, a mixed martial arts fighter in California, and his wife Mishel Eder lost their 15-month-old son, Liam, to a drunk driver. The culprit was a 72-year-old woman who had been drinking at the local VFW hall before she hit the toddler, who was in a stroller being pushed by his aunt.

Mishel Eder holding the hand of her 15-month-old son, Liam, before

taking him off life support. He was hit by a drunk driver in 2016.

Kowal is from Sweden, where the BAC limit was lowered from .05 percent to .02 in 1990, and where the drunk-driving death rate is much lower than in the United States. He was shocked when he realized the extent of the problem here. He and his wife started a nonprofit to push for a .05 BAC limit in the United States, and they’re currently working with filmmakers to make a documentary about drunk driving. The couple recently met California Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D), who’s now running for governor. Newsom helped them draft a bill to lower the BAC limit to .05. But so far, they say, they have not been able to find a single member of the state legislature willing to introduce it. “It’s frustrating when California is so forward thinking in so many ways that it’s so hard to get someone to stand behind a bill that will so clearly save so many lives,” says Kowal.

Correction: An earlier version of this article mischaracterized MADD’s proposal for mandatory ignition interlocks. In addition, it mischaracterized the scope of Alcohol Justice’s advocacy for a .05 BAC law, which is happening on a national level.