Hardline immigration policies put in place by President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have inspired more than just fear and panic in immigrant communities—they’ve also inspired investors in private prisons. In the week following the 2016 election, stock prices for the country’s two biggest prison companies rose by around a third, largely on the promise that the new administration would reverse the Obama administration’s move away from doing business with prison companies.

A year and half later, with the administration’s immigration crackdown in full swing, Immigration and Customs Enforcement is forecasting that next year will bring a 23 percent increase over the already historic number of people it locked up daily in 2017. That’s good news for companies like CoreCivic and the GEO Group, which take in millions of dollars from ICE to detain people awaiting immigration or asylum hearings. And they’re already planning to expand, with proposals for new private detention centers from Minnesota to Texas.

The growth of immigration detention

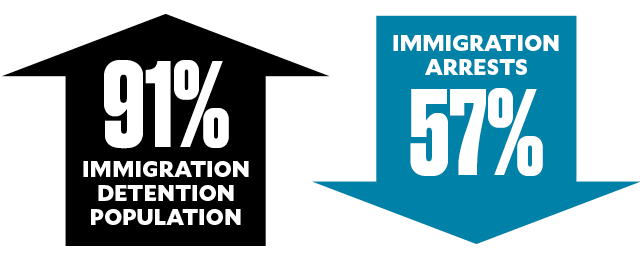

Between 2002, when the Department of Homeland Security was created, and 2017, the total number of immigrants arrested by ICE and apprehended by the Border Patrol fell by more than half, correlating with lower levels of illegal immigration. Yet the average daily population of US detention centers nearly doubled.

Who’s detained?

More than 300,000 people are put into immigration detention annually. Nearly three-fourths of those held each day are kept in privately run facilities, according to an ICE facility list obtained by the nonprofit Detention Watch Network. (Just 9 percent of state and federal prisoners are held in for-profit facilities.)

People in ICE detention are largely from Mexico, Central America, India, and China. They include adults and children, and they’re held for up to two months on average. Some are detained for years, with no right to an attorney.

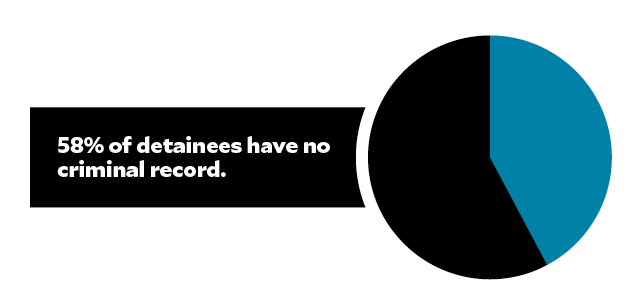

According to an internal ICE report from July 2016, fewer than half of the people booked into immigration detention that year had been convicted of a crime.

Of every 100 immigration detainees…

32 are in GEO Group facilities

21 are in CoreCivic facilities

21 are in other private facilities

26 are in public jails

Locking up profits

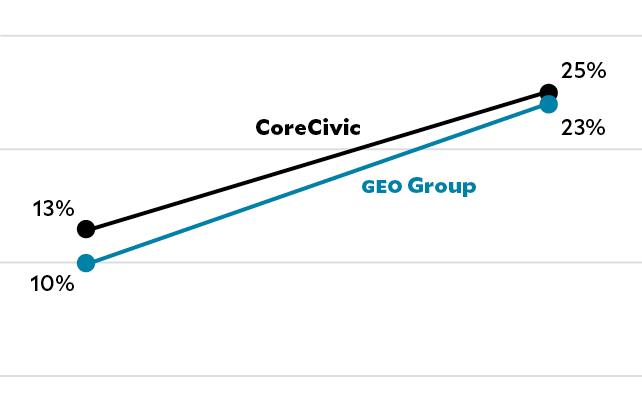

As private prison companies have grown over the last decade, they’ve increasingly relied on immigration detention to boost business. Here’s the share of company revenue coming from ICE in 2007 versus 2017, according to filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The price of immigration detention

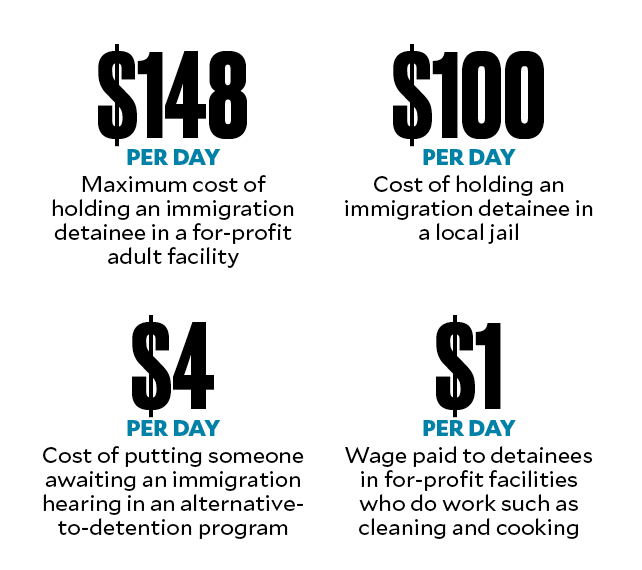

Last year, ICE told Congress that it expects to hold a record 51,379 detainees in 2018, at a total price tag of $2.7 billion.

The agency’s 2019 budget request lays out the costs of detention:

How we got here

- 1996: President Bill Clinton signs legislation expanding mandatory immigration detention.

- 2004: The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act ramps up immigration detention capacity by 32,000 beds.

- 2010: Congress sets a quota for the number of immigration detention beds.

- 2012: GEO Group, the nation’s largest prison company, hires a senior executive who was previously assistant director of enforcement and removal for ICE—one of several revolving-door hires between ICE and private prison companies.

- 2014: Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic) announces its new South Texas Family Residential Center, which by 2016 would provide 14 percent of total company revenue. Immigrant advocates brand it a “baby jail.”

- 2016: After the Obama Justice Department says it will cease contracting with private prisons, a Department of Homeland Security council votes to stop using private facilities to detain immigrants. A GEO Group subsidiary gives $225,000 to a pro-Trump super-PAC. GEO Group and CoreCivic each donate $250,000 to President Donald Trump’s inauguration fund.

- 2017: The Trump administration says it will continue to work with private prisons. GEO Group and CoreCivic spend $2.6 million on federal lobbying. The immigration court backlog swells to more than 650,000 cases before 292 judges.