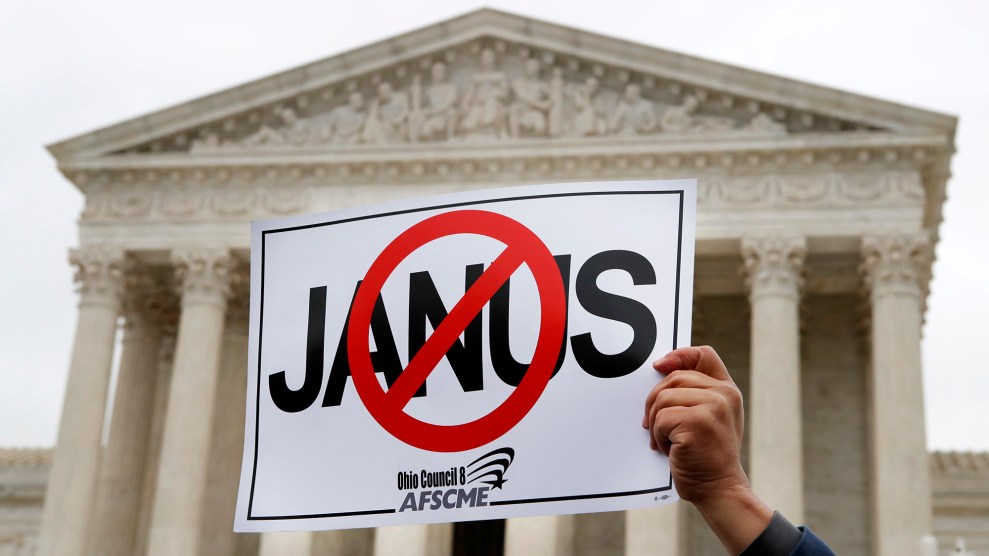

A pro-labor demonstrator outside the Supreme Court in February 2018.Jacquelyn Martin/AP

The Supreme Court ruled on Wednesday that public sector workers cannot be required to chip in to the unions that represent them. The 5-4 ruling in Janus v. AFSCME deals a devastating blow to the labor movement and one of its most critical sources of funding.

Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the majority, said that charging these fees “violates the free speech rights of nonmembers by compelling them to subsidize private speech on matters of substantial public concern.”

Union leaders feared that the court would weaken labor with its decision. “It’s clear that moneyed interests are behind this case and it’s obvious that it is nothing more than a political attack to further rig the system against working people,” American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees President Lee Saunders in a written statement prior to the ruling.

The plaintiff in the case was Mark Janus, a child support specialist employed by the state of Illinois who decided that he did not want pay dues to the union that negotiates on his behalf. While unions cannot force workers to join, they can require employees in unionized workplaces to pay a “fair-share” fee to cover union benefits.

Lawyers for Janus argued that forcing workers to help finance unions infringes on their First Amendment right to freedom of speech. Anti-union crusaders such as the State Policy Network painted the case as a way to “defund and defang” unions.

Unions countered that this question had been resolved nearly 40 years ago. In 1977, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education that union dues weren’t a serious threat to free speech, but that unions must erect a financial wall between their workplace activities and their political activism to ensure that they weren’t forcing employees to contribute to political activities.

There are 17.3 million employees of state and local governments; of those, 58 percent are represented by unions, according to the Economic Policy Institute, a pro-labor think tank. Prior to today’s ruling, the EPI argued that black women—who make up nearly one-fifth of public employees—would suffer the most from an anti-union decision in Janus.

Kate Bronfenbrenner, the director of labor research at Cornell University, warns that the ruling could add to the sense that organized labor is headed for extinction. “It takes power to change the law,” she says. “The only time the labor movement has actually gotten labor law reform is when they organized like crazy.”

AFSCME says the decision will only intensify its ongoing organizing efforts. “Over the last few years,” Saunders writes, “we’ve trained more than 25,000 members to step up and become activists, nearly 18,000 workers have joined through new organizing drives, and we’ve held nearly 900,000 personal conversations with members about the value of union membership.”