The “photograph of the missing being…will touch me like the delayed rays of a star.” —Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography

Last year, Asya Ivashintsova-Melkumyan and her husband were renovating their house near St. Petersburg, Russia (formerly, Leningrad), when they stumbled in the attic on an oversized box among her late mother’s belongings. Inside they found a treasure trove: 30,000 negatives and occasional prints packaged in envelopes with handwritten comments and dates.

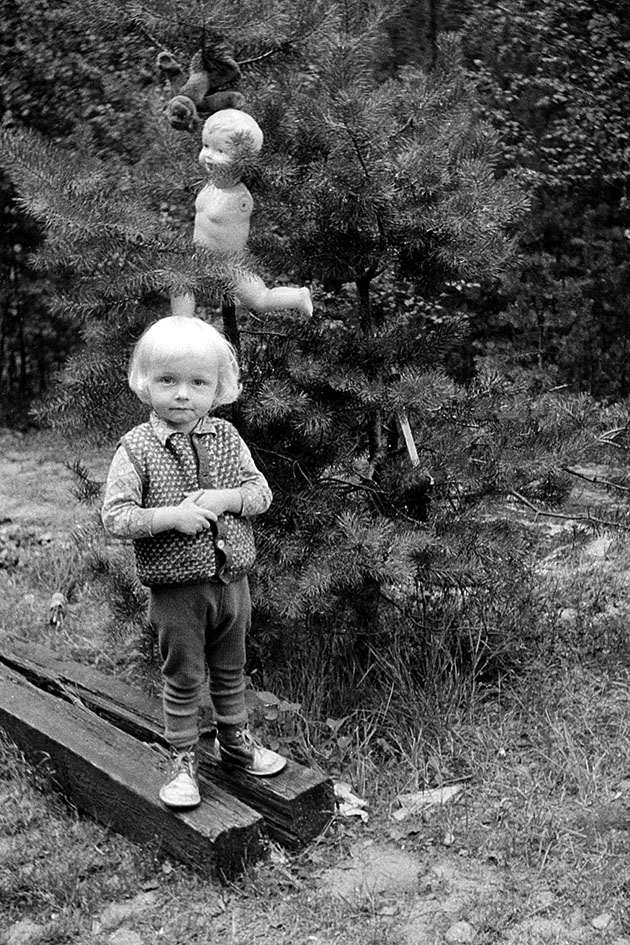

The archive contained a photographic record of everyday life in the Soviet Union and post-communist Russia created by Asya’s mother, Masha Ivashintsova (1942-2000). Here was street photography of Leningrad and Moscow, images of Ivashintsova’s travels across the USSR, photos of Asya as a child, dilapidated courtyards, old pets, imperial statues, cramped Soviet apartments, portraits of lovers and strangers, beggars and babushkas. Ivashintsova captured countless facets of Soviet life from 1960 to 1999: schoolchildren playing in the snow, alcoholics guzzling beer in the squares, communist rallies, weddings, passersby posing with cigarettes in fur hats, Soviet fashions, quotidian objects like washbasins, moods reflected off the surfaces of the age.

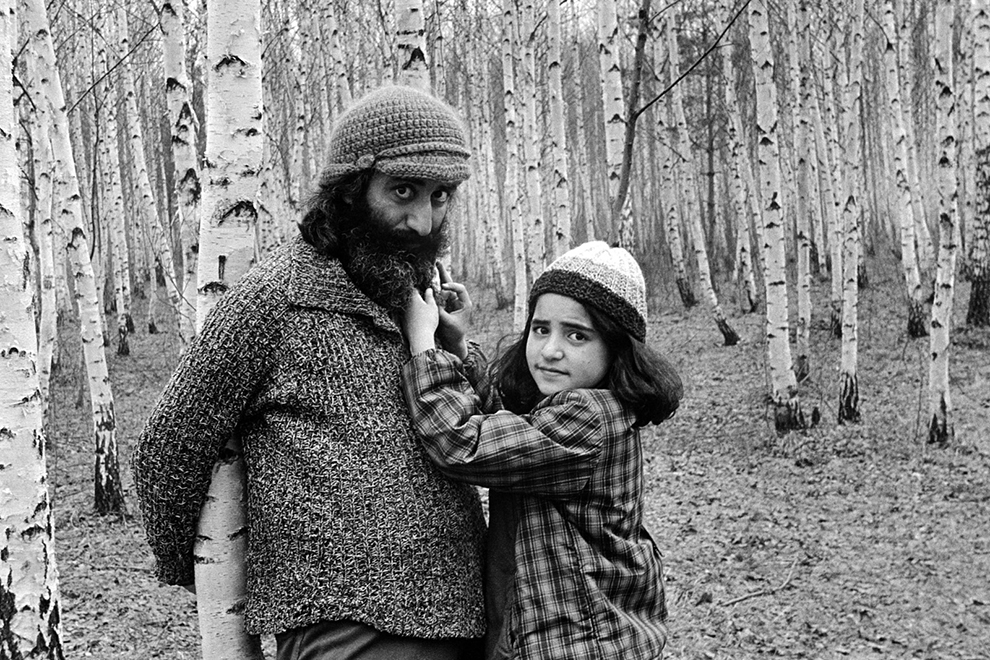

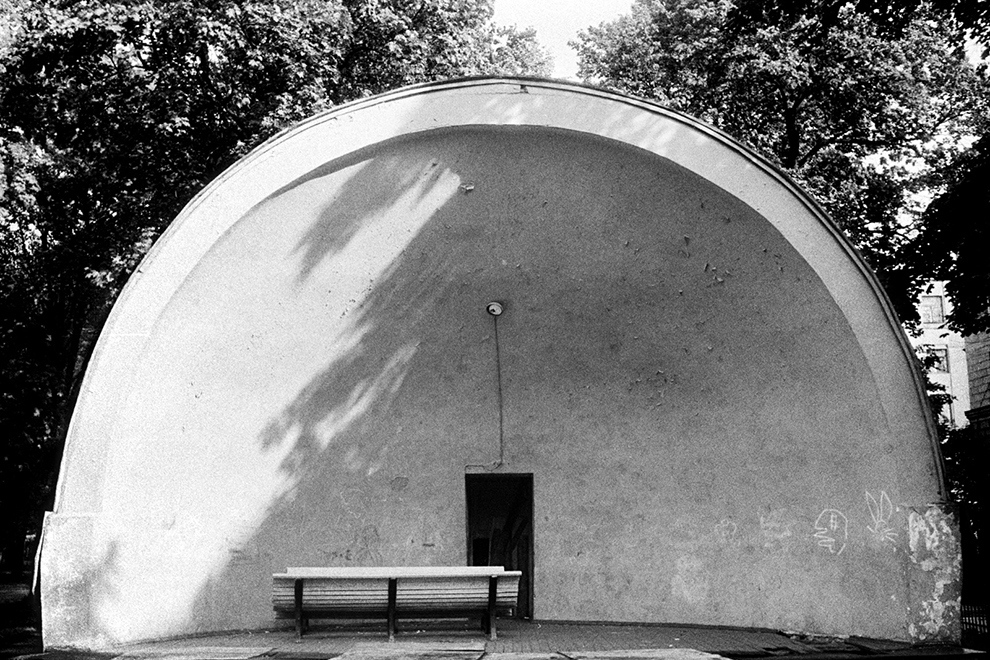

Leningrad, 1979

Until that moment, no one had seen Ivashintsova’s pictures. She kept her work private and rarely printed it. Even her family members didn’t suspect that she was a serious photographer. “Taking photographs for my mother was like breathing,” Asya says. “I never thought that it was something special.”

This is a story about a woman whose photographic obsession left a rare historical look into the USSR and whose secrets are now being discovered by her daughter. Ivashintsova’s archive offers a glimpse into the world beyond the Iron Curtain through the aperture of her life. The photographer used her camera to create a day-to-day record of loves big and small. She identified with what she saw–a lover, a dog in a muzzle, a child on the street–and imprinted upon it her aura.

“My mother is teaching me to see,” says Asya, who is digitizing the images and showcasing them on a website dedicated to her mother’s work. “Now, I am peering into my life through these photographs.”

Asya Ivashintsova-Melkumyan, Masha’s daughter, with dog Marta and cat Pusya, Leningrad, 1978

For Asya, each picture is a time capsule. “I remember many details, which I see in those photographs,” she says. “I remember those textiles, those interiors, light, sounds. Here my hand lies on my dog’s Marta collar and it’s like I am feeling again her fur under my hand.”

Yet the majority of Ivashintsova’s photographs contain moments Asya could not have remembered. Her parents separated in the early 1970s. Asya remained in Moscow with her father, Melvar Melkumyan, an Armenian-born linguist. After the collapse of the marriage, her mother moved back to Leningrad to live as a creative free spirit in a country that frowned on creativity and individualism.

In Leningrad, Ivashintsova joined the city’s literary and artistic underground. She worked odd jobs–as a theater critic, a librarian, a cloakroom attendant, an elevator mechanic, and a security guard, among others–and became romantically involved with two celebrated figures of the era, the poet Viktor Krivulin and the photographer Boris Smelov. Occasionally, she would visit Asya and Melvar in Moscow.

Asya with her father, Melvar Melkumyan, a few years after the marriage between her parents collapsed, Moscow, 1976

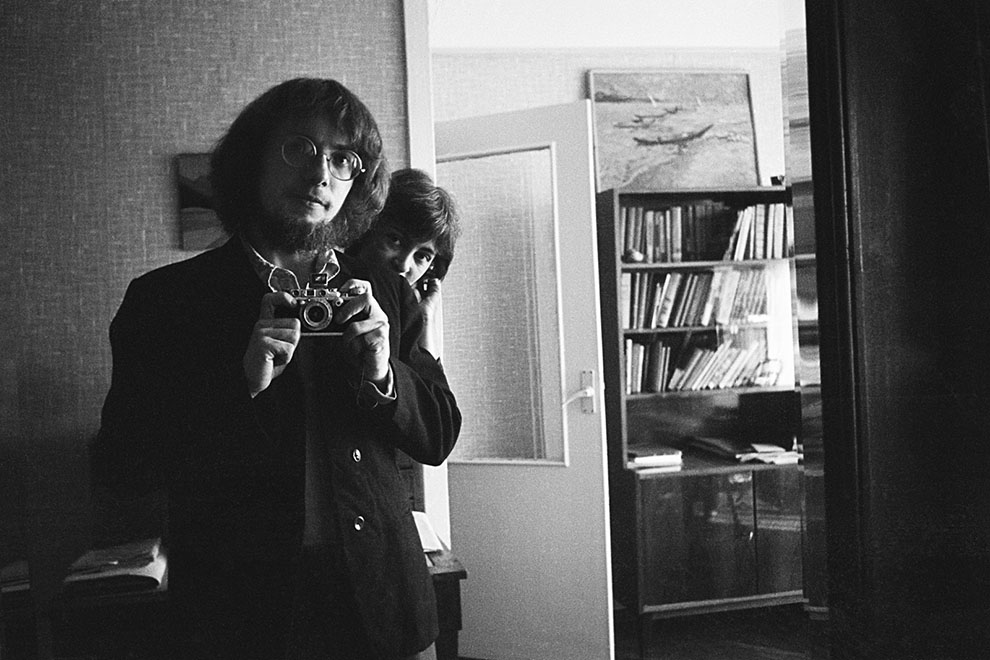

When Ivashintsova first met him, in 1974, Boris Smelov was the rising star of Leningrad’s photography circles. His ethereal, lyrical images of the city are to Leningrad what Eugène Atget’s are to Paris. They stand without precedent, influenced more by Fyodor Dostoevsky and St. Petersburg’s long-standing literary tradition than by street photography’s canon.

Masha Ivashintsova with her lover, photographer Boris Smelov, Leningrad, 1974

It was Smelov who gave Ivashintsova his Leica as a gift, a camera she would use for the rest of her life. A key influence on Ivashintsova as a photographer, Smelov’s renown was perhaps one of the reasons Ivashintsova was too insecure to share her work.

If Smelov was a poet whose medium was the camera, Ivashintsova was a chronicler committing the world to memory. On the surface, her documentary-styled pictures profess a factual truth: This happened then. Yet each one is also a reflection of the artist in everyday life: a self-portrait masquerading as the USSR. Preserving moments that touched her, Ivashintsova inextricably tethered them to her life. “All of this was an expression of her essence,” Asya says of her mother’s work. “It was her substance and her language.”

Resident of a village near Lake Sevan, Armenia, 1976

In the above portrait of an Armenian villager Ivashintsova met near Lake Sevan, we can see the sitter’s response to the photographer. Ivashintsova reflects in the woman’s hospitable gaze: the gleam of her eyes, her tender half-smile, her wrinkles. We can sense Ivashintsova’s presence on the other side of the viewfinder, impressing itself on the scene from some invisible foreground.

The ability to project herself into the frame and the longing to preserve those she photographed are the hallmarks of Ivashintsova’s work. Her images are not pegged to decisive split seconds or abstract juxtapositions. They are intimate dialogues between the self and the other, whose reverberations continue long after what’s in the picture is gone.

Unlike many photographers who wear what Dorothea Lange called a “cloak of invisibility”, Ivashintsova took pictures to forge a visible connection. In a country where photographing strangers without a press pass could have aroused suspicion, Ivashintsova courageously sought out communion with ordinary Soviet citizens, sealing their reactions to her gaze inside the emulsion of film.

Orehovo, 1976

Leningrad, 1981

Staraya, 1976

Her presence animated her subjects, even when they were made of stone or metal.

Leningrad, 1977

Leningrad, 1978

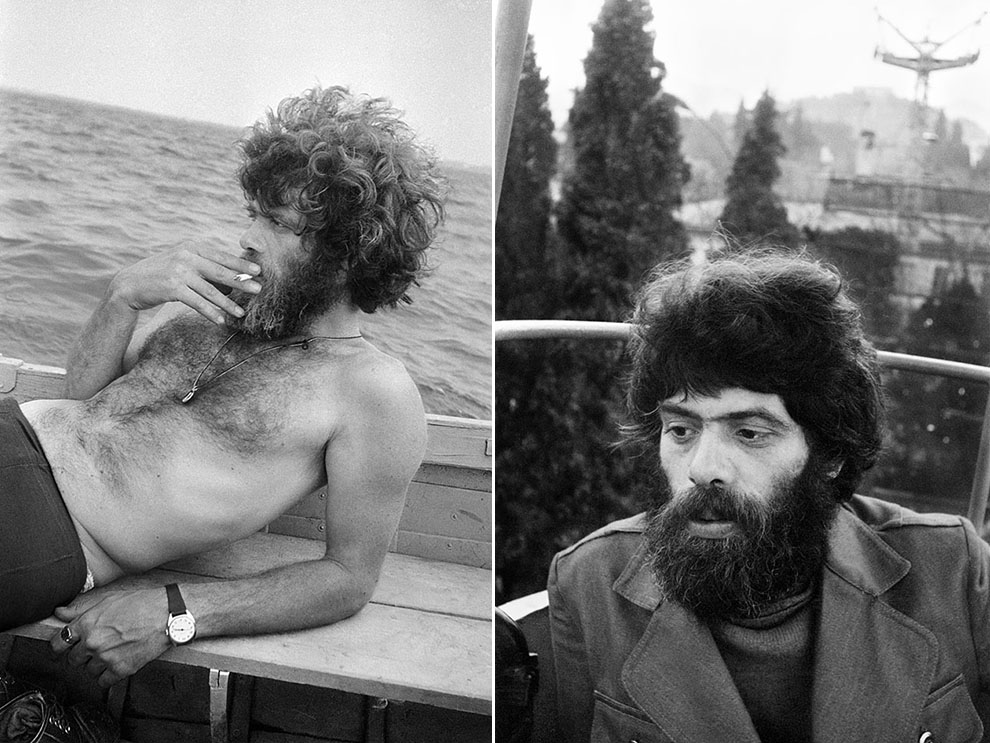

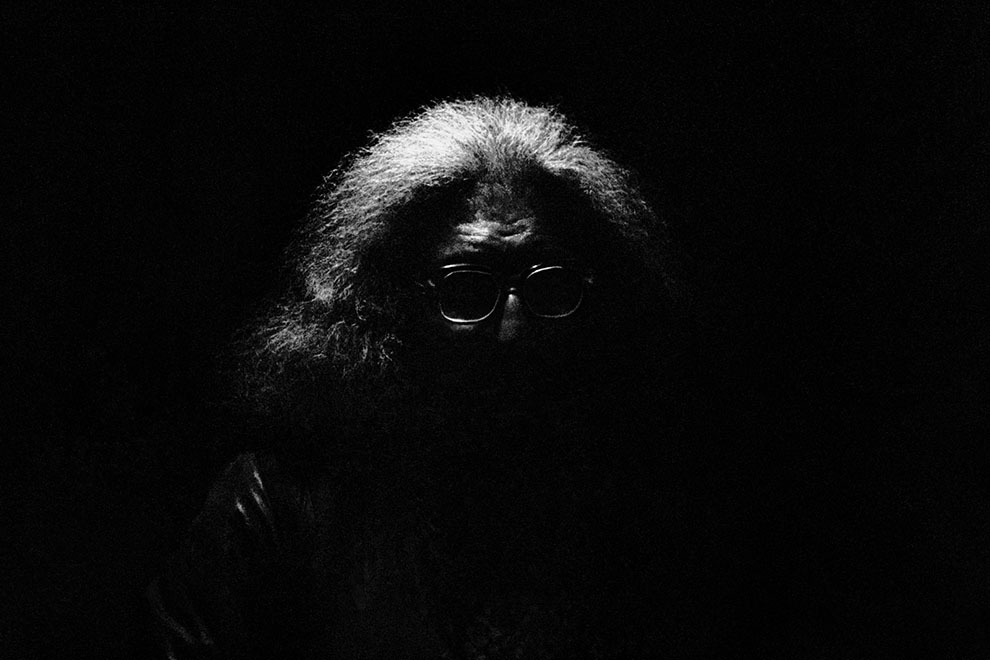

Among Ivashintsova’s photographs were portraits of her second great love, the poet Victor Krivulin who was a lynchpin of Leningrad’s unofficial literary circles. As a young man he dared to show his poetry to Anna Akhmatova-one of the greatest 20thcentury Russian poets-whose house he frequented. Crippled from childhood, Krivulin walked with a cane, published underground samizdat journals, and organized readings and seminars in his tiny communal apartment: a place where Leningrad’s writers and artists gathered, talked and drank through the night. The local K.G.B. authorities tried to get the brilliant troublemaker to leave the country, but Krivulin chose to remain in communist Russia without being permitted to publish his work.

Viktor Krivulin: Novolukoml, Belarus, 1979 (left); Yalta, 1979

The relationship between Ivashintsova and Krivulin was as passionate as it was tumultuous. According to Asya, “they were together, then they split up, then they were together again, then they split up again.”

Also among her mother’s belongings, Asya found the poet’s letters and her mother’s diaries in which Ivashintsova talks about her relationship with Krivulin. Talking about what it was like to read those diaries while still coping with Ivashintsova’s absence, Asya says, “I have had a real revelation of my mother’s internal life-how vulnerable she was and how much she had to go through.”

The family’s discovery alerts us to the possibility that those we know might, too, be making brilliant art in secret, and the likelihood that people’s inner lives are often more fragile and richer than we might imagine.

Ivashintsova has been compared to Vivian Maier, the Chicago nanny whose 100,000 photographs of street life were discovered posthumously at an auction. Both women took pictures without sharing them and greatly underestimated the quality of their work; both liked to photograph their own reflections. Like Maier, Ivashintsova was a loner who, according to Asya, “shunned society.” Both also suffered from mental illness.

By 1981, Ivashintsova was crippled by worsening depression and became jobless. “My mom lost herself,” Asya says. “She lost herself in the desire to fit into social norms of that time, but also in the desire to remain herself. By her very nature she could not betray herself.”

Unemployment was a crime at that time in the Soviet Union, and authorities gave Ivashintsova a grim choice: prison or forced commitment to a mental hospital. Ivashintsova chose the latter. For the next 10 years, she was in and out of Soviet psychiatric hospitals, where she was, according to Asya, eventually “broken” by medications.

During the Brezhnev era and later, the Soviet regime relied on psychiatric confinement for political reasons. Dissidents who stood up for civil rights, asked to emigrate, or distributed prohibited books could be locked away in a hospital without a trial. Living outside the norms and dictums of a communist society, Ivashintsova was bulldozed by Soviet psychiatry. Incredibly, she continued to take pictures during those years. Indeed, those she took in the mid-’80s are some of her darkest, and, at times, her most profound.

Leningrad, 1986

Take this one of an empty band shell with peeling paint and broken floorboards-the kind that had once sprung up everywhere across the USSR to promote proletariat leisure. The shell looks like a hollow cranium without eyes, blind to the trees looming beyond it. Bespeaking entrapment, the mise-en-scène might have come straight out of Samuel Beckett. The stage is a symbol of self-erasure: disturbing and inescapable. All that is left is a small chalked graffiti of a human and a rabbit head and a doorway leading into the void of a midsummer’s day. Behind the trees is an official building, which might be a hospital. The image is laden with dark, oppressive sensations, and they crawl up the observer’s spine.

Melvar Melkumyan, husband and father, Moscow, 1987

Leningrad, 1983

Digitizing her mother’s negatives, Asya says, has felt like “raising a vessel full of gold coins from the bottom of the sea.” For her, the photographs are portals into the labyrinths of time. We, too, can peer into their world wherein, picture after picture, we seek out Ivashintsova only to discover a vanished civilization, the pathos of distance and a talent worth celebrating.

You can learn more about Masha Ivashintsova on the website Asya and her family set up to show her work. You’ll find the latest digitized images on this Instagram: @masha_ivashintsova.