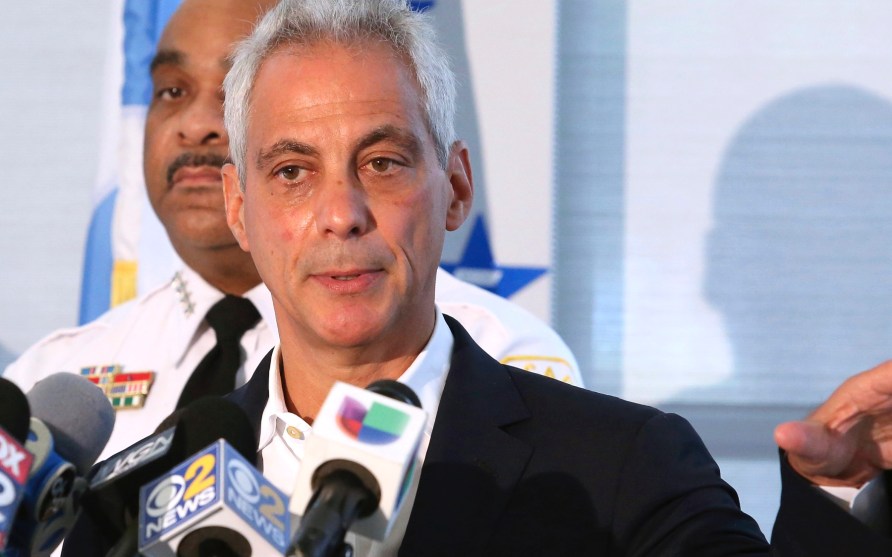

Lori Lightfoot at a press conference regarding the findings of a federal investigation into the Chicago Police Department in January 2017.Santiago Covarrubias/Sun-Times/AP

The way things are shaping up, it’s a fair bet Chicago’s next mayor will be a woman of color. The question is, “Which one?”

Mayor Rahm Emanuel stunned the city last week when he announced he wouldn’t seek a third term in office. Now, in the first truly open race since 1983—when Chicago elected its first black mayor, Harold Washington—one of the top contenders is Lori Lightfoot, a 56-year-old attorney who would be the first black woman (and the first openly gay person) to run Chi-town if she survives—and that’s a big “if.”

“She’s a very bright person with a lot of passion and a lot of candor,” says Lawrence Oliver, who worked with Lightfoot as a federal prosecutor and later on the board of the Better Government Association. “She has the ability to assess things quickly, to propose solutions and just see things with a critical eye and an honest eye in a way that persuades others in many cases to see things like her.”

Lightfoot had come at Emanuel from the left with a platform calling for a $15 minimum wage, more investment in neighborhood schools, and increased police accountability. She was widely seen as the incumbent’s biggest rival in a crowded field of a dozen or so hopefuls. And while some local politics watchers figure Lightfoot could handily beat her current batch of rivals—including former schools chief Paul Vallas and former police superintendent Gary McCarthy, whom Emanuel fired amid public uproar about the Laquan McDonald shooting—the entry of other powerful women of color into the race could spell trouble for her campaign.

In the long history of Chicago, there has been only one woman mayor and one elected black mayor—and they weren’t the same person. Now Susana Mendoza, the state comptroller, and Toni Preckwinkle, sitting chair of the Cook County Democratic Party, are hitting the phones to see how much support they can drum up, according to the Chicago Tribune. On Monday, Preckwinkle announced she would be making a decision “shortly.” Other big players are weighing runs, too, according to local news reports, include former Commerce Secretary Bill Daley, whose brother and father both served as mayor, 2011 mayoral candidate Gery Chico, and US Reps. Luis Guiterrez and Mike Quigley—who both represent parts of Chicago.

“Lightfoot is the most credible of the current crop, has the most robust campaign operation, has raised real money,” says Tom Bowen, a Democratic political consultant who in the past served as a deputy campaign manager and political director for Emanuel. “That said, now that this is an open seat, who else might join the race?”

“That’s very bad for Lori,” he adds.

Lightfoot, the youngest of four siblings, was raised in a predominately white section of a segregated Ohio steel town in the 1960s and 1970s. Her parents worked low-wage jobs to support the family. Her father always held two or three, she says. She was the only black student in her elementary school, she told me, and her early experiences with racism and sexism imbued in her a desire to fight for equality. Things didn’t get any easier when she began to grapple with her sexuality in high school and college. “People said things. I got denied opportunities solely on the basis of my race or my gender. Overt racism was still very much on the table,” she says. “I had in me from an early age the need and a desire for fairness and for justice.”

During the 1980s, Lightfoot worked her way through the University of Michigan. She later attended law school at the University of Chicago and remained in the city, where she now lives with her wife and their 10-year-old daughter. After several years in private practice, Lightfoot served a stint as a federal prosecutor before going to work in city government. She ran the Chicago Police Department’s Office of Professional Standards, a civilian unit that investigates complaints of police misconduct. Later, she served as chief of staff and as general counsel at the Office of Emergency Management and Communications, which runs Chicago’s 911 call center. Richard M. Daley, Emanuel’s predecessor, tapped her to head the city’s Department of Procurement Services and revamp its minority- and women-owned business program. She ultimately returned to the law firm Mayer Brown, where she is a partner.

In 2015, in the wake of the Laquan McDonald shooting, Emanuel appointed Lightfoot to run the Police Board—an independent civilian body that hears disciplinary matters related to serious police misconduct—a position she resigned from to run for mayor. After video of the McDonald shooting went viral, sparking citywide outrage, Emanuel chose Lightfoot to head his Police Accountability Task Force, whose scathing final report on policies and procedures concluded, among other things, that the department’s own data supported “the widely held belief the police have no regard for the sanctity of life” of people of color.

Lightfoot recently released a critique of a draft consent decree being negotiated between the state attorney general and Chicago police. The critique points to pieces she felt were lacking, notably a mandatory plan aimed at reducing city spending on settlements, judgements, and legal fees related to police abuse claims—which have cost Chicago more than $700 million over 15 years. Making sure city officials stick to the final agreement will be among her top orders of business, Lightfoot says.

She also wants to put aside more money for Chicago’s neighborhood schools—as opposed to the magnet and charter schools that were a hallmark of Emanuel’s education policy. “People feel like they can’t stay in the city because there’s no choice for them through schools that they can go to and walk to as a family,” Lightfoot says. “We send a message to those kids that where you live is not worth our investment, and I think that’s exactly the wrong message.”

Long-term investment in black and brown neighborhoods, she insists, will be key to stamping out the violence that has long plagued the city. In 2016 and 2017, Chicago had more homicides than New York City and Los Angeles combined—although the death toll is down significantly this year.

Emanuel has faced considerable heat from Chicago’s black community—including homegrown activist and superstar Chance the Rapper, whose recent single, “I Might Need Security,” calls on the mayor to resign over the alleged cover-up of the McDonald shooting. Emanuel’s school closures in black and brown neighborhoods haven’t helped him there either, nor has rapid gentrification. In January, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Chris Kennedy accused Emanuel of having a “strategic gentrification plan” to force black residents out and make room for wealthier white ones—Emanuel fervently denied it. “People don’t feel like government works for them,” Lightfoot told me. “They feel like elected officials and the remnants of the Democratic machine here only work for themselves.”

Lightfoot, who has never run for elected office, may have a tough time getting the votes she needs should either Preckwinkle or Mendoza, both people of color with broad support, jump into the ring. The filing deadline for the February 2019 mayoral election is November 26, and several of the potential new candidates are formidable. “They’re proven fundraisers. They have records on issues that are important to special interest groups and voters,” Bowen says. “They’re known for things that they’ve done in Chicago, and Lightfoot is still unproven and unknown to a vast majority of Chicago voters.”

Preckwinkle, black and well-established, could be a particular threat to Lighfoot. She “has been in politics for 25 years,” Bowen says, and has a solid base among constituencies Lightfoot needs on her side. At a press conference shortly after Emanuel’s announcement, Lightfoot cautioned voters against flocking to newbie candidates. “Many of us have been out here for months making our case to Chicagoans,” she said. “Anyone who decides to jump in to take advantage of today’s political news, I think a fair question to ask them is, ‘Where have they been?'”

Emanuel told the Chicago Sun-Times last week that his supporters are now being hit up for endorsements, but he doesn’t plan to endorse anyone personally. (A recent poll suggested that 45 percent of Chicago voters would be less likely to vote for an Emanuel-backed candidate.) Emanuel’s exit may also free up millions of dollars from his would-be supporters—a prolific fundraiser, he already had more than $10 million in his campaign war chest. In July, Lightfoot, who leads in fundraising among the remaining field, reported just over $500,000 in donations. Several consultants told me a winning campaign will require at least $5 million.

On a whim, I asked Lightfoot if she would be vying for the support of Chance the Rapper, a staunch Emanuel critic. On several touring stops in 2016, Chance set up booths where concertgoers were encouraged to register to vote. After a show in Chicago the day before the November election, Chance marched hundreds of fans through downtown to a polling station where they could cast their votes early.

Lightfoot paused and then laughed at my question. It turns out she has an indirect Chance connection. Back in 2011, the rapper recorded his first mixtape, 10 Day, at a studio and digital media center created for teens at the Harold Washington Library downtown. The center was a pet project of Lightfoot’s wife, Amy Eshelman, the former assistant commissioner of Chicago’s public libraries—now there are satellite media centers at several library branches. “He’s doing what frankly I wish a lot of artists would do, which is use the platform that they’re given to really focus like a laser beam on social justice issues that are really relevant to their community,” Lightfoot says. “I think everybody wants Chance the Rapper’s endorsement!”