In his new book, The Corrosion of Conservatism: Why I Left the Right, Max Boot goes further than the handful of other prominent Republicans who have stood against Donald Trump and reconsiders the conservative movement writ large. He sat down to discuss his epiphany with Washington bureau chief David Corn for the Mother Jones Podcast. This is an edited and condensed transcript of that conversation.

David Corn: You were a golden boy of conservative punditry. You joined the Wall Street Journal editorial page in 1994 at 24. You were the op-ed editor four years later. You became a contributing editor to the Weekly Standard and a blogger for Commentary. You were in neocon heaven—a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, an adviser to John McCain in 2008 and Mitt Romney in 2012. You were one of the major voices in favor of the Iraq War. And in your forthcoming book, you write with great introspection and humility, “I can finally acknowledge the obvious: It was all a big mistake. Saddam Hussein was heinous, but Iraq was better off under his tyrannical rule than the chaos that followed. I regret advocating the invasion and feel guilty about all the lives lost.” I mean, Max, this is almost, maybe it is, an apology. What brought you to that point?

Max Boot: Well, it’s basically that I could not deny reality indefinitely. Anybody looking around Iraq today can see it is not the democratic paradise that George Bush and Dick Cheney and others promised in 2003. I’m certainly not the only one who has confessed their errors here. John McCain did before his death. But many right-wingers have stuck to their guns rather stubbornly. And I think the only way you’re going to improve US foreign policy and set a sound course for the future is if you’re willing to look back at what went wrong before. One of the lessons I draw from the Iraq War is be pretty darn careful about launching preventative conflicts. And that’s not a lesson that everybody has learned. For example, John Bolton, before he became national security adviser, was arguing in favor of preventative military action against both Iran and North Korea, which I think is crazy. I certainly got a big one wrong in the case of Iraq.

DC: Well, let me pick at the scab a little. What do you think the original sin was?

MB: There were two assumptions. One was that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, and I think that was an honest error, although I do think policymakers in the Bush administration were not willing enough to engage with contrary points of view. But from that honest mistake, very dubious conclusions were drawn. I was certainly one of those who imagined because Saddam was such an evil dictator that we could vastly improve life for people in Iraq and throughout the Middle East by toppling him. In hindsight, containment was a much better option. Underlying my assertion was a naive and hubristic faith in American power. I fled the Soviet Union as a child. And some of that naive faith was based on the experience of Eastern Europe after the fall of the Soviet Union, where we saw these democracies develop. Of course, if we had waited a little bit longer, we would have seen how fragile even those democracies are today in places like Hungary and Poland. But in 2003, a lot of people, including me, had this naive faith that democracy was the wave of the future, and that the United States was at the vanguard, and that we could do good for humanity, and good for America’s strategic interests, by getting rid of Saddam Hussein. And obviously those assumptions have not been borne out.

DC: Why do you think it’s so hard for people now to concede they got it wrong?

MB: Well, a general danger of punditry is that there’s very little incentive to change your position or admit error. If you reverse your position, the people who backed you before will be unhappy, but a lot of the people who now agree with you will still pillory you. I’ve gotten that on Twitter; I’m called a war criminal and told that I’m being opportunistic in renouncing the Iraq War. And so these people on the left are basically saying, “Too late. You can’t renounce your beliefs.” There’s very little incentive, from a political economy standpoint, for people to reverse field. And a lot of disincentives. You see that now with Trump, who claimed the handling of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, where 3,000 Americans died, was a tremendous success. And he’s rewarded for that by his followers. I mean, the Trump theory is that if you admit error then you’re showing weakness and you’re going to get destroyed politically. You can argue that could be correct, as a matter of politics. Obviously, as a matter of intellectual honesty and accuracy, it’s an appalling standard by which to hold yourself.

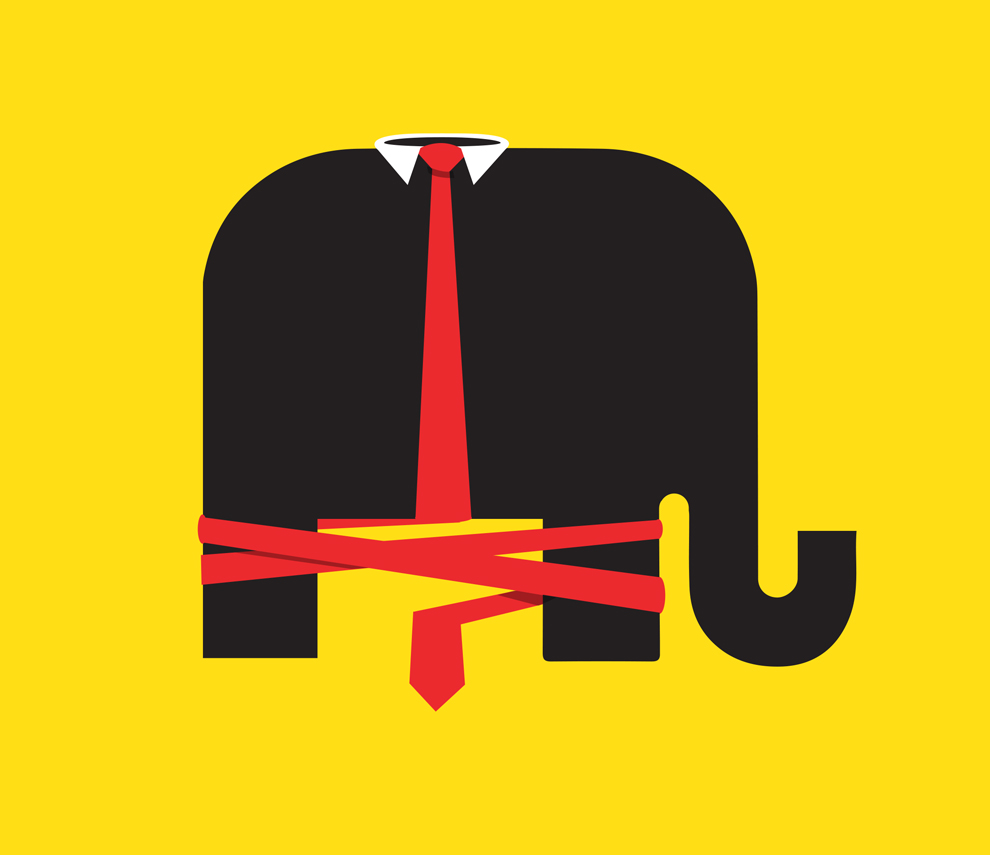

Max Boot

Mother Jones illustration; Amanda Gordon/Bloomberg/Getty

DC: You’ve been moved to reconsider much more than just Iraq. You wrote, “I am now convinced that coded racial appeals—those dog whistles—had at least as much, if not more, to do with the electoral success of the modern Republican Party than all of the domestic and foreign policy proposals crafted by well-intentioned analysts like me. This is what liberals have been saying for decades while accusing the Republican Party of racism. I never believed them. Now I do.” When did Boot become woke?

MB: I’m ashamed to admit that it took the emergence of Donald Trump. I was in my conservative bunker, and I thought this was a gross libel against the Republican Party to claim that we were catering to racism, or that it was a libel on America to claim that America was a pervasively racist society. And then Trump came along and I realized, “Wait a second. There is a much larger constituency for racism and xenophobia than I had realized.” And it made me think, “Oh, my goodness. This is why a lot of people were voting Republican.” It wasn’t because they loved supply-side economics. It wasn’t because they supported NATO. It was because they were looking for a candidate who would champion the interests of white people. And Donald Trump did that more unabashedly and more unapologetically than previous Republican candidates had done. That was a wake-up call. And then of course I saw other examples of racism coming to the fore in ways that were undeniable, like all these videotapes of police officers killing and abusing African Americans. The evidence is right there, on the tape. You can’t deny it. African Americans have been saying for years that they have been the victims of racist police, but I tended to believe the police officers. Same with the #MeToo movement, which made me realize, “Hey, feminists have a point when they talk about the abuses of patriarchal society and the suffering that women endure in America.” To be clear, I’m not buying into some kind of anti-American worldview. We have made real progress, but I think we have a long way to go. I think a lot of my fellow conservatives are in denial about the state of modern America.

DC: To me, this part of your book is fascinating. Because the Iraq War, it’s a policy mistake. But race is really one of the fundamental debates and divides we have. And it’s been an article of faith, on the conservative side, that they have been libeled on this front. We see a hue and cry anytime Republicans are confronted with this issue. Why this inability to see at least a portion of this?

MB: I can talk about my own blindness. I thought, “I’m not racist. And I’m a Republican. So it seems like a gross libel to accuse Republicans and conservatives of being racist if I personally am not racist.” And what I’ve realized is there are a lot of racists that the Republican Party is appealing to. There’s also been a disconnect between what Republicans do in office and what they do on the campaign trail. Because going back to 1964, when the parties basically switched positions on civil rights, Republicans have been appealing for white votes with coded racial appeals. Whether it was Nixon’s Southern strategy, or in 1980 Ronald Reagan kicking off his general election campaign in Philadelphia, Mississippi, or the Willie Horton ad from George H.W. Bush. You can point to all these examples. But when you look at the actual Republican presidents and leaders, I think they were actually decent people who weren’t delivering on this white-power agenda that a lot of their supporters might have been led to think they would deliver on. And so you had a disconnect between the Republican Party on the campaign trail and the Republican Party in power. Trump exploited that, because he has no compunctions about doing in office the kind of things that previous Republican standard-bearers only hinted at on the campaign trail. And he is tapping into frustration in ranks with what they see as being RINOs, as Republicans in Name Only. What I think they mean by that is candidates who did not deliver on the kind of racist, xenophobic, white-power agenda that a lot of Republicans would actually like to see. Before Donald Trump, the Republican Party was a majority conservative party with a white nationalist fringe. Now it’s a white nationalist party with a conservative fringe.

DC: You saw people lining up behind Trump when he got the nomination. It seems to have prompted a crisis of faith within you.

MB: Yes, it has. I wrote in 2016 that Donald Trump was a character test. And sadly, almost the entire Republican Party has failed. I am appalled to see people who I think are essentially decent, like Paul Ryan or George W. Bush, still campaigning for Republican candidates. They somehow disassociate ordinary Republicans from Donald Trump. But what we’ve seen consistently since Trump came into office is there is no separation. The Republican Party is now the Trump party. As John Boehner said, the real Republican Party is off taking a nap somewhere. This is the Trump party. They’ve basically made a Faustian bargain, where they say, “Give us judges and tax cuts and we’ll look the other way, at your racism, your xenophobia, your insanity, your attacks on our allies.” They’ve basically sold out for the judges and for the tax cuts. And for me it’s an appalling bargain.

DC: Is there any difference now between conservatism and Trumpism?

MB: There is a small group of “Never Trump” conservatives. But it is a small group, and I’ve actually been surprised that there are not more of us. There’s enough of us for a dinner party, not a political party. I wish there were more. Within the grassroots, a lot of people really love the Trump message, the racism, the xenophobia, the nonstop insults against liberals. That’s actually what they like most about him. And in Washington, there are a lot of cynical people who say, “Well, Trump has the support of 84 percent of Republicans, so we can’t get on his bad side.” These people that I used to admire have sold out their principles. Nobody’s more shocked and surprised than I am. This is a movement to which I dedicated my whole life. And now I realize, what the hell was that about? Who were these people? They’re not who I thought they were.

DC: But what does it mean for you, personally, to be untethered in this way?

MB: It makes me realize how much of American politics is tribal and how little of it has to do with principles or ideas. The reason why so many people are Republicans is because they hate Democrats; the actual substance of what Republicans stand for almost doesn’t matter. And that’s been a shocking realization. I reregistered as an independent the day after the election and no longer think of myself as a member of that community. On a personal level, it’s been a difficult experience because much of my identity was tied up in the conservative movement. And it’s hard for me to talk to a lot of my friends—the gap between us is so wide. But I’ve also realized the extent to which I had tailored my public statements to what the movement would find acceptable. I didn’t say anything I didn’t believe in, but there was a lot of stuff that I just didn’t comment on. I think it’s crazy that Republicans are opposed to all gun control when we have such a rampant problem with gun violence. But I just never tackled it. Or when Republicans deny climate change, which is a scientific fact, I didn’t deal with it. I just stayed in my lane, foreign policy and national security policy, and ignored the craziness all around me. I went with the tribe. I took the path of least resistance, and now it’s making me realize, no, I’ve got to think for myself, and that’s something very few people do, because being part of one of these political tribes, as much as anything, is a substitute for thought. So it’s been both chastening and liberating to escape from that stifling orthodoxy.

DC: In the book, you write, “Only if the GOP as currently constituted is burned to the ground will there be any chance to build a reasonable center-right political party out of the ashes.” So your position now, Max, is burn, baby, burn. It sounds like the old Marxists.

MB: I respect some of my friends trying to work on reforming the Republican Party, but at least for the time being, I think it’s a lost cause. So my hope is that the Republican Party will suffer massive and repeated drubbings at the ballot box. That’s why I urge everybody to vote straight-ticket Democratic even though I have a lot of disagreements with Democrats. I’m not a Democrat; I’m an independent. But for the health of our republic, I think we need to destroy the Republican Party. We need congressional oversight of Donald Trump, which you’re never going to get out of Republicans. I think you need to punish the Republicans for taking these appalling positions, abusing minorities, championing white nationalism, isolationism, protectionism. The only way to wean them from that is to punish them electorally.

DC: As a man without party, a man without ideology, with maybe fewer friends than you used to have, are you feeling hopeful or more in a despairing sort of mindset?

MB: I am a lot less optimistic or, if you like, Pollyannaish about the future of America than I used to be. I was this immigrant kid who came here in 1976 from the Soviet Union, and I’ve always believed in America and the goodness and greatness of America, and that’s really been my greatest faith. And that faith has been battered. This is a country that could elect Donald Trump. People like me kind of arrogantly assumed it can’t happen here, that there’s something in the water in America that renders us immune from this kind of threat to our democracy. And lo and behold, we’re not immune. We could easily go the way of countries that are backsliding from their democracy. I don’t think that’s inevitable, and I think the checks and balances in our system are stronger than in other countries. I’ve been cheered to see the way the press has taken on Trump. I’ve been cheered to see what the Democrats have done even as a minority in Congress, and the courts, and also the federal bureaucracy—even some of Trump’s own appointees. If Trump could get away with it, I’m sure he would love to emulate Putin and impose a dictatorship of his own. But, mercifully, we’ve had over 200 years of democratic tradition, and we do have pretty strong institutions. But we’re not as different from the rest of the world as I had previously thought, and so I’m no longer as optimistic about America. And I am pretty pessimistic about the survival of the American-led world order that we created in 1945. I mean, if you’re an American ally, why would you ever trust America again?

DC: I suppose all our moods will be severely impacted by what happens on Election Day.

MB: Absolutely. If Republicans hold on to the House and Senate, Donald Trump will see that as a green light to do the worst. Within a couple of days, he’s going to fire Sessions, Rosenstein, Mueller. He’s going to pardon Manafort and everybody else. It’s going to be a catastrophe without precedent for American democracy. He may still do that even if Democrats win, but if Democrats can take control of at least one house, there’s going to be some pushback, there’s going to be some subpoenas, there’s going to be some investigation, and basically the American people will be sending a cry and saying, “No, we will not put up with this. We will not allow you to undermine and even destroy our democracy. We’re going to stand up for the principles of 1776.” Every election people say there’s a lot at stake, but this time I really think that’s true.