Hotline volunteer Erica Waller takes about 30 calls a day from Georgia voters. Kiera Butler

By all accounts, it’s not a great time to be a voter in Georgia. In the past six years, more than 200 polling places have shuttered across the state. Since last July, officials have dropped 107,000 people from the list of registered voters, mostly because they haven’t voted recently. Thanks to a law passed last year, the state can reject voters if the information on their registration doesn’t exactly match existing state and Social Security Administration databases. Under this law, Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp—who also happens to be running for governor—has stalled 53,000 registrations, mostly from African American voters.

To navigate that obstacle course requires a certain amount of political savvy—which is why, in the run-up to the midterm elections and a super-competitive governor’s race, Georgia Democrats have set up a dedicated hotline to answer questions from perplexed voters. It’s an impressive operation: In an office building off an Atlanta highway, 180 trained volunteers work in shifts to field about 300 calls a day. In the week after news of the 53,000 stalled registrations broke, the hotline received more than 500 calls a day. The staffers work from 8:30 a.m. to 9 p.m., but when late-night callers leave messages, they get a call back first thing the next morning.

Last week, I went to see the hotline in action. Under fluorescent lights in a converted conference room, about 20 volunteers were working the phones, stopping occasionally to refuel with pretzels and soda stashed on a desk in the corner. Among the crew was Erica Waller, who had been taking 30 calls a day for about two weeks. A California transplant, Waller said the news about the hurdles her fellow voters faced sparked her interest in volunteering for the hotline. “I got tired of talking about it, and I said, ‘Let’s just do something here,’” she said.

Most of the calls Waller takes are straightforward. They’re from voters who have recently moved and don’t know where their new polling place is, or those who aren’t sure what county they should vote in. But some are more complicated. The day before I visited, she said, a voter from the city of Augusta, in the southwestern part of the state, had called in a panic because her county hadn’t accepted her registration through the Department of Driver Services (DDS) and the deadline for new registrations had passed. Waller figured out there had been a communication error between DDS and the county, and she got the voter on the rolls. “She was able to vote, and she was thrilled,” Waller said. “That was really exciting.”

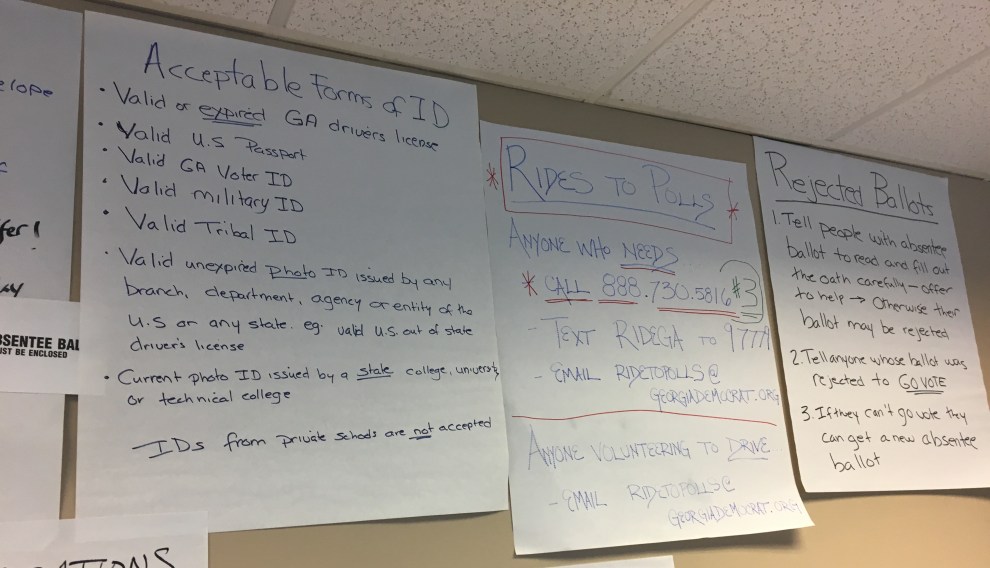

Handmade posters remind hotline volunteers how to address various concerns from voters.

Kiera Butler

Maggie Chambers, the spokeswoman for the Georgia Democrats, said the hotline team receives many calls from people who have run into problems with the exact-match requirement. In one recent example, a volunteer traced a caller’s problems back to the fact that unbeknownst to him, a DDS employee had entered his middle initials on his driver’s license as “NMN”—shorthand for “no middle name.” When she explained the error to county officials, they fixed his registration.

Chambers said her team had received a fair number of calls from people on the list of the 53,000 voters whose registrations had been stalled. Mostly, she said, they wonder how they got on the list in the first place, and the volunteers are trained to try to help them figure that out. If they can’t, they explain that people on the list are still allowed to vote in November as long as they bring ID (though confusion about this will likely still keep some of them from the polls).

As Election Day approaches, the team is trying to spread the word about the hotline, especially to non-English-speaking communities, where confusion around name matches and registration rules can run especially high. For this reason, staffers have publicized the hotline in foreign-language media outlets and recruited volunteers who take calls in five languages. The efforts seem to be paying off: Waller told me her callers come from all kinds of ethnic backgrounds and from all over the state.

Still, Chambers wishes voting in Georgia were easy enough that a hotline wasn’t necessary—and she blamed Kemp for the extra hassles. (His office also maintains a phone line to answer questions about elections during business hours, but it often refers voters back to their counties.) Kemp, she charged, “has spent years working to disenfranchise and intimidate voters of color in Georgia, and now he is running for the highest office in Georgia while barely hiding the fact that he wants fewer people of color to vote.” Despite that, she said, she was optimistic that “they are still making their voices heard in record numbers.”

This post has been updated for clarification.