Bettmann/Getty

I was home in San Francisco earlier this year when my mom told me that our family had a connection to Peoples Temple.

We had just finished brunch and were crossing Divisadero, one of the main thoroughfares of the Western Addition neighborhood, also known sometimes as the Fillmore, in which we had both been born and raised. I think I must have prompted her on the subject, asked her if she’d realized the 40th anniversary of Jonestown was coming up in November and if she had known anyone who died there. That’s when she turned to me in the cross walk and said quite matter-of-factly: “Of course.”

Then she nodded her head north and told me where the church’s headquarters had been, a short walk from us. I stood next to her, a little shocked, a little eager, a little worried this was all I’d get from her. My mom’s prone to yawn off historical moments, figuring if you’re lucky enough to live through something, there’s no sense in talking about it.

She didn’t grow up in a particularly religious family—my grandmother had been something of a rebel, ditching her own parents’ thrice-weekly churchgoing for the local pool halls—but one of my mom’s close friends from junior high, Francine Mason, wouldn’t stop nagging her about a new church she found. It was a welcoming church for all people, it proclaimed to see all people, black or white, as equal, Francine had told her.

It was an era of opting in, in a neighborhood where there was no shortage of things to opt into. There was the rock scene at the Fillmore Auditorium, drug addled hippies in the Haight-Ashbury. The Black Panthers had an office near Divisadero. But Peoples Temple, the church my mom’s friend was so into, was bigger and and more politically influential than nearly everything else in the city in the mid- to late-’70s. Beyond that, part of the appeal was that it didn’t make you wait for the afterlife to find salvation. If the gas company was skimping on service but still badgering you about the bill, members would coordinate letter-writing campaigns. If your grandmother couldn’t afford retirement, the church provided free housing and food on a pristine patch of land two hours north.

Maybe it’s not so surprising then that my mom finally caved to her friend’s pressure and visited the church once. She spoke about it with me with all of the enthusiasm of recounting something strange that happened that one time at the laundromat: On the day she visited, she said, some old lady in wheelchair suddenly said she was able to walk, the congregation cheered, and my mom left. “It was weird.”

That was the moment that really helped crystalize for me the blackness of Jonestown. Peoples Temple was a hugely influential part of black San Francisco at one time, embedded so deeply that middle schoolers like my mom took time to check it out. On some level, I knew this intuitively, that some hulking part of the community I had grown up in had been scarred by this infamous American tragedy. For years, I’d heard vague stories, about aunties and cousins who went off to Guyana and disappeared. But, over the past year, the more I asked people in my community about Jonestown and Peoples Temple, the more I came to understand how close it still is to the surface of everyday life in the Fillmore, even decades later. One person remembered being hospitalized as a kid in the same unit as a young member of Peoples Temple, and becoming pen pals with a person who had come to visit the bed-stricken churchgoer. My high school English teacher taught creative writing to Temple children and later published a book featuring the students’ work.

I in turn became somewhat obsessed with understanding the church, the institution of black political life then. But more accurately, I wanted to know about that woman my mom described in the wheelchair, about the friend who urged her to go in the first place. I needed to know about the individuals, largely black individuals, who were so seduced by the church’s white leader, and who were, more importantly for me, mostly forgotten—either erased or shamed from history. I wanted this not because I was afraid of them or even morbidly fascinated, but because on a deep level I felt I understood them and this perhaps-foolhardy desire to belong—especially today, almost exactly 40 years later.

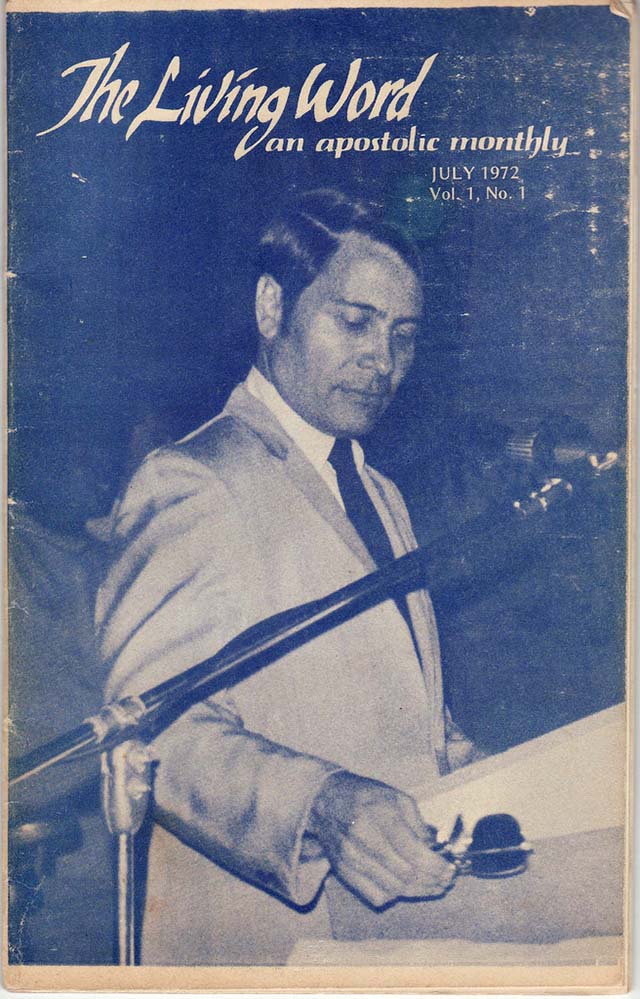

The Living Word magazine with Jim Jones on the cover, 1972

Trying to unpack the meaning of Jonestown and its leader, Jim Jones, has become a genre in its own right. Peoples Temple was a church and socialist political movement that began in Indianapolis in the 1950s before migrating to California and opening congregations in Redwood Valley, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. In 1977, the church established what it called an “agricultural project” in a remote outpost in Guyana, where its leader and hundreds of his followers set about establishing a socialist utopian Promised Land. Instead, on November 18, 1978, 918 people died at the behest of Jones, who called the action “revolutionary suicide.” There are memoirs by survivors, like Deborah Layton’s Seductive Poison. There are documentaries, including Stanley Nelson’s Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple. There are more recent historical looks at Jones and how he built the church, like Jeff Guinn’s The Road to Jonestown.

The vast majority of these popular accounts center predominately on Jones, who was white, and the perspectives of white survivors. Each anniversary of the massacre, though, brings a more sober look at how race functioned within the church, like Sikivu Hutchinson’s 2015 novel White Nights, Black Paradise. More than 90 percent of Peoples Temple members were African American. Jones even modeled the cadences and substance of his preaching on those of a black spiritual leader named Father Divine, a sort of T.D. Jakes of the early 20th century. Of the roughly 1,000 Peoples Temple members who moved to Guyana before its tragic end there, 70 percent were black and almost half were black women. A number of those were black women over the age of 61; the burgeoning community relied in part on the $36,000 per month in Social Security benefits that these women brought in.

I can see why the church and its drive to build a colorblind utopia appealed specifically to black people in this San Francisco community. The Fillmore was once called “the Harlem of the West,” a black neighborhood dominated by jazz bars, mom-and-pop shops, and Victorian duplexes in varying degrees of upkeep and decay. Like most black communities, it was a place of government-sanctioned racial segregation, one of only two neighborhoods open to black people, where black doctors didn’t live that far from the poorest of the poor. By the 1970s, black families in San Francisco were struggling with drug addiction and neglect; the neighborhood was still reeling from a two-decade-long redevelopment program that demolished hundreds of homes and displaced tens of thousands of residents. It was mostly the poor who were left to live in a smattering of public housing complexes that took up most of the neighborhood.

Members of Peoples Temple attend an anti-eviction rally at the International Hotel, San Francisco, January 1977.

Nancy Wong/Wikimedia

What’s more, the church became the place where radical and progressive dignitaries, the people many of these neighbors looked up to, came to show their worth: Angela Davis visited and once gave a radio dispatch talking about the “conspiracy” against the church. Dennis Banks, who had been part of the more than year-long occupation of Alcatraz with the American Indian Movement, also reportedly showed up. Willie Brown, who would become San Francisco’s first black mayor but was then a California state assemblyman, was a strong supporter. Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett, the influential publisher of the city’s black newspaper, became the publisher of the church’s newsletter and was also the personal physician of the church’s reverend.

Even still, in America, Jonestown is largely seen as a white catastrophe; in Guyana, it’s viewed as a distinctly American one, a late-20th-century experiment in colonialism. In both tellings, and in the many books and films, black people are seen en masse, without individual stories of their own that might tell us something about how private entities learn to prey on black people when civic institutions fail them, and how joy can sometimes be found within that.

So I went looking for names.

Shortly after that conversation with my mom, I stumbled across a website that has become a digital repository for all things related to Jonestown and Peoples Temple with the somewhat clunky name of “Alternative Considerations of Jonestown & Peoples Temple,” or, for short, Jonestown Institute.

Think of it like Reddit, except that every user is a survivor, family member, long lost friend, or curious passerby to what, excluding natural disasters, amounts to the largest single loss of American civilian life outside of 9/11. What’s so special about it is that it fills in the holes of all the other narratives I’d read. There is a detailed accounting of all 914 Temple members who died that day, along with hundreds of hours of audio recordings from the Temple, transcripts of those recordings, and memorials dedicated to the dead. There are testimonials and songs from former members. And there is the largest collection of individual photos of Temple members on the internet.

More than a database, I found the Jonestown Institute is also a broad, resilient community that has spent 40 years trying to understand itself. Members who were young adults during the Temple’s existence are now grandparents, and I was surprised by how frankly they speak about how they may not be around for much longer but are still determined to archive their experiences so that humanity won’t repeat their mistakes. They are also quick to point out that there was beauty in coming together, in fighting for something beyond themselves in a time of political uncertainty and social isolation.

Nearly all of this is thanks to the work of one couple, my guides: Rebecca Moore and Fielding “Mac” McGehee III, neither of whom ever stepped foot in Jonestown but wound up dedicating decades of their lives to the macabre task of humanizing its victims.

Moore and McGehee were living together in Washington, DC, when news about the massacre in Jonestown broke. They were on their way out the door for a morning jog when McGehee caught a glimpse of the day’s Washington Post: Leo Ryan, the congressman from California, had been shot and killed while investigating an American church group living tucked away in the jungles of Guyana. At least some of the camera crew and concerned relatives who had traveled with Ryan had also been wounded, according to initial reports. Meanwhile, it was unclear what had happened to the church members.

Moore was immediately worried. Her older sister, Carolyn, and younger sister, Annie, were both ardent Temple members who had been living in Guyana for two years. Carolyn even had a three-year-old son, nicknamed Kimo, with Jones. Moore hadn’t seen either sister since they moved to Guyana, though they often sent Moore and their parents letters, urging them to join.

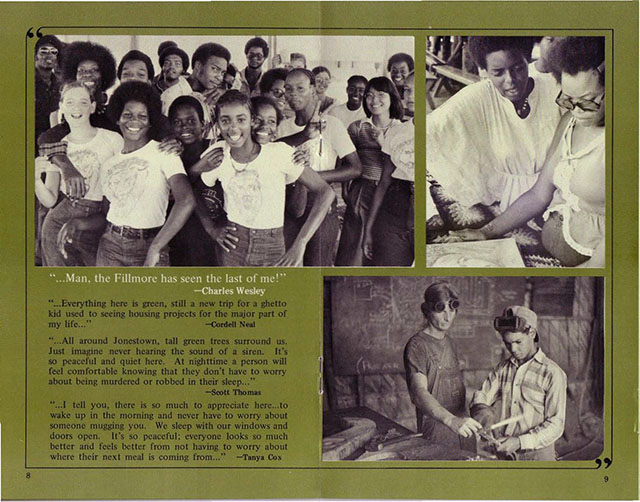

Pages from “A Feeling of Freedom,” a pamphlet extolling virtues of living in Jonestown.

As the days passed and news surfaced of the overwhelming death toll, Moore was gripped by an awful realization. Not only were her sisters dead, but they had both likely helped orchestrate the deaths of hundreds of others. Both women had worked their way into the small, tight-knit, and almost entirely white inner circle that governed Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Carolyn, who had been a high school English teacher before joining, ran much of Jonestown’s K-12 education curriculum. Annie was trained as a nurse. More than 900 people—many of them children—ingested or were injected with a lethal dose of cyanide-laced Flavor Aid at Jonestown, but there were people who had to buy it, mix it, and distribute it. Those people likely included Annie and Carolyn Moore. “The thought of my sisters killing children made me physically sick,” Moore later wrote. “I couldn’t believe they could do such a thing. But if they had? I hoped they were dead as well.”

Moore wanted answers about what had really happened, but those proved hard to get amid a slew of sensational headlines, like “Peoples Temple Cult: Violent Outer Fringe” and “FBI Checking Reported Plot by Sect to Slay Government Leaders.” The Washington Star compared Jones to Charles Manson. “Every paper looked like the National Enquirer,” Moore later noted. McGehee says they made a decision: “We’re the ones who are left”—they could either put it behind them, or, he said, “step forward and try to explain to the world who these people were.”

Both were trained journalists and almost immediately they began submitting Freedom of Information Act requests for thousands of hours of audio recordings and other records that were taken from the compound in Guyana by the FBI before even the bodies had been evacuated. Slowly, those tapes began to trickle in—including the infamous so-called “death tape,” in which Jones is heard encouraging his followers to drink the poison amid wails and screams from the crowd. Around 1999, McGehee vowed to transcribe each and every recording in order to make the content more readily available. It turns out there are 964 (all of which the FBI has since made publicly available online). He still has hundreds more to go.

He would also later devote himself to compiling a list of every person who had died at Jonestown, with the help of the California Historical Society. It was perhaps an even more painstaking process. Only several hundred bodies were in good enough condition after the massacre to be identified and sent to families; several hundred more were so badly decomposed from laying stacked atop one another in the sun for days that they could not be immediately identified, and some 400 were eventually buried in a mass grave at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California. “I just recall sitting there with [McGehee] and really knowing the importance,” Frances Kaplan, an archivist at the California Historical Society, told me. “This is people’s lives that you’re responsible for and so we really wanted to make sure that we not just got their name correctly, but spelled their name correctly.”

Meanwhile, Moore earned a Ph.D. in religion and became a professor, writing extensively about medieval Christian ideology, Jewish biblical commentary, and, of course, Peoples Temple. In 1985, she published a book, A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in Peoples Temple. Unlike the many other memoirs offering up salacious details about life in the church, it never reached a wide audience. When I read it, I was several chapters in before I realized that Jones’ name had appeared only a handful of times. It is a work dedicated to the people who are wholly forgotten in the retellings of Jonestown. “They were more than just faceless bodies rotting in the sun,” Moore would later say.

In 1998, around the 20th anniversary of the massacre, Moore put her work about Peoples Temple online, and it became the basis of the Jonestown Institute. The timing wound up being fortuitous—the 20th anniversary marked a turning point in the remaining Jonestown community. Many had lived for years still in shock over what happened, and shamed for seeming to have allowed it. They were distrustful of outsiders, and, at times, even more distrustful of one another. But by then, enough time had passed for some of those open wounds to scab, and for survivors to seek out one another as a salve in larger, organized groups. The website became an important meeting place.

What I find most staggering on the site is the prominent “Who Died” section, which lists each person in alphabetical order. If you click on someone’s name, you can see their nicknames, place of birth, when they arrived at Jonestown, their parents, siblings, and partners. And then there are the “Remembrances.” This is where friends and family leave short testimonials about the person in question. Some knew the victims personally. But many others are distant relatives, some learning about an aunt, or a cousin, or a grandmother for the first time.

There’s Marcus A. Anderson, named after his uncle, who was 15 when he died at Jonestown. There’s Joyce Marie Brown, 18 when she died at Jonestown, who was a “lovely girl with a beautiful spirit,” according to her creative writing teacher, Judy Beebelaar, who also added a poem Brown wrote in class. Edna May Bowman was 48 when she died at Jonestown, but her surviving family still tells stories about her, according to her granddaughter, Jawana. “Whole families died over there,” my mom tells me later over the phone. And she’s right—it’s jarring, generations gone in a matter of hours. The Hicks family from Detroit lost four. The Moton family from Philadelphia lost five. The Lewis family from San Francisco has stuck with me the most: They lost 27.

“Imagine having your entire life be defined by how you died, and no one knows anything else about you other than your death,” Moore says. “They know nothing about what you did, what your name was, what you looked like, what your hopes and aspirations were, what your failures were.”

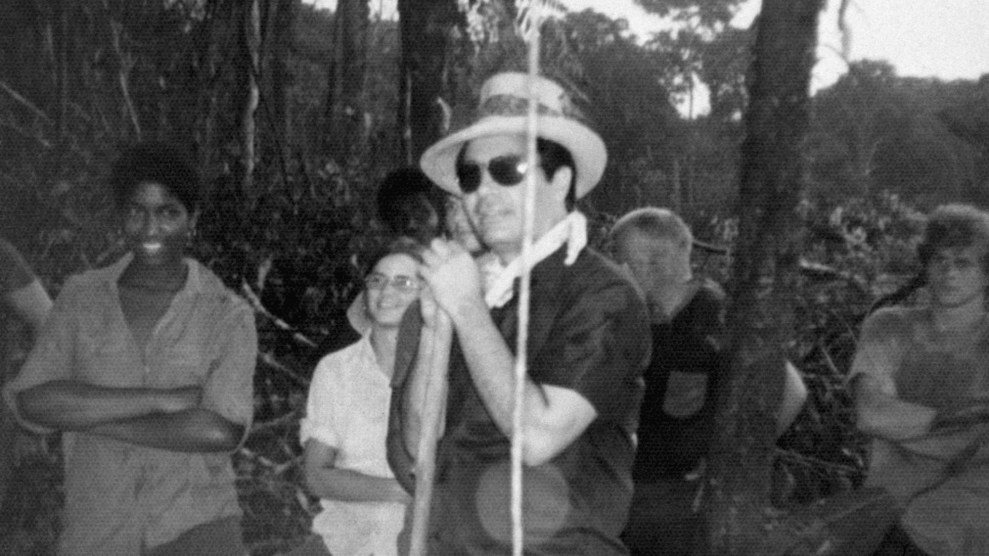

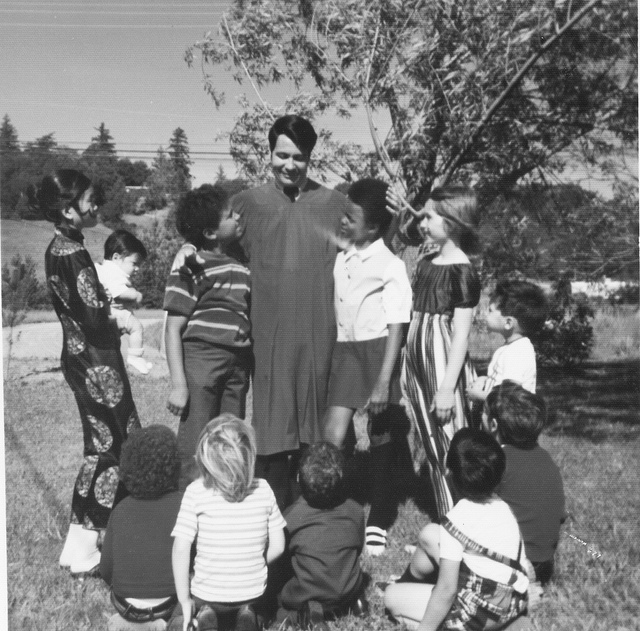

Jim Jones with his “rainbow family” in Redwood, California, 1972.

Beyond chronicling the individuals, Moore and McGehee have also taken pains to grapple with the role of race in Jonestown’s legacy. Moore, for her part, recalls feeling uncomfortable when she visited her sisters at the church’s property in Redwood Valley, California, noticing how few black people were directly in Jones’ orbit. Just after we spoke, McGehee sent me a 33-page academic paper that Moore’s been working on about how Jonestown’s black victims have been erased, and how they’ve begun to re-insert themselves—through some firsthand accounts, but also by simply coming together and talking to one another about what they’ve lost—into a narrative that has its own layers.

On the site, I also found my mom’s friend, Francine Mason. She was 23 when she died at Jonestown. Her partner, Eddie James Hollman, also died there, along with their one-year-old son, Tiquan. So did Francine’s mother-in-law and niece. I was sad to see there’s not currently anything posted on Francine’s remembrance page, but my mom remembers.

“She was a nice, pleasant person, funny,” she says in a somewhat guarded tone, seeming to still want to protect her friend’s privacy. “We were young, it was different than you guys,” she says, referring to my generation’s tendency toward asking a million questions. “We were taught to keep our business to ourselves. Every family was private.”

I came away from all of this with a deeper appreciation for just how average Peoples Temple members seemed. I went into it thinking that I’d find people who were misunderstood, maybe, but also brainwashed. Their inclination to be part of something was ultimately misguided, but nonetheless, it was human. But now, crucially, through Moore and McGehee, I also deeply understand how possible it is to build a life from tragedy, and how necessary it is to sift through what’s most painful, year after year after year, to better understand how it’s shaped you.

The irony isn’t lost on Moore. After rejecting the church when her sisters were alive, she’s spent the decades after their deaths more enmeshed in the Temple’s existence than really anyone. Her involvement goes beyond the study of the Temple and its meaning. Once, when I tried to arrange a time to talk with her, I hear from McGehee that she’ll be busy helping a former Temple member move in Indianapolis, even though the couple lives in a remote part of Washington state. “[My husband] and I occasionally ask ourselves, ‘What would we be doing if Jonestown had not happened in 1978?’,” she told me. “And the fact is we’ve been part of Peoples Temple much longer than my sisters ever were part of the movement.”

I became fascinated with Jonestown not because I was repelled by the idea of people mindlessly following along on some wild journey to build a utopian community, but because, on some level, I got how they did. I know how it feels to want to be a part of something that is separate but still part of the community in which you’re raised. I wasn’t born until nearly a decade after Jonestown, but the Fillmore I grew up in was one besieged by stories of loss. It was the Dot Com boom of the late 1990s, and all around me were stories of black families who were leaving the city because their rents were too high, their property taxes had skyrocketed, or the violence and neglect of the preceding decades left them aching for a fresh start elsewhere.

It’s extremely lonely and vulnerable to be born and raised and black in San Francisco these days. My mom is aging, and I’m a thirtysomething living 3,000 miles away and feeling increasingly anxious about the amounts of care I’ll have to provide to her on my own. For this, and so many other reasons, in this time of tribalism and instability, with inequality on the rise and people feeling moved to find a political savior, Jonestown is still worth revisiting. So too are the people still surviving it.