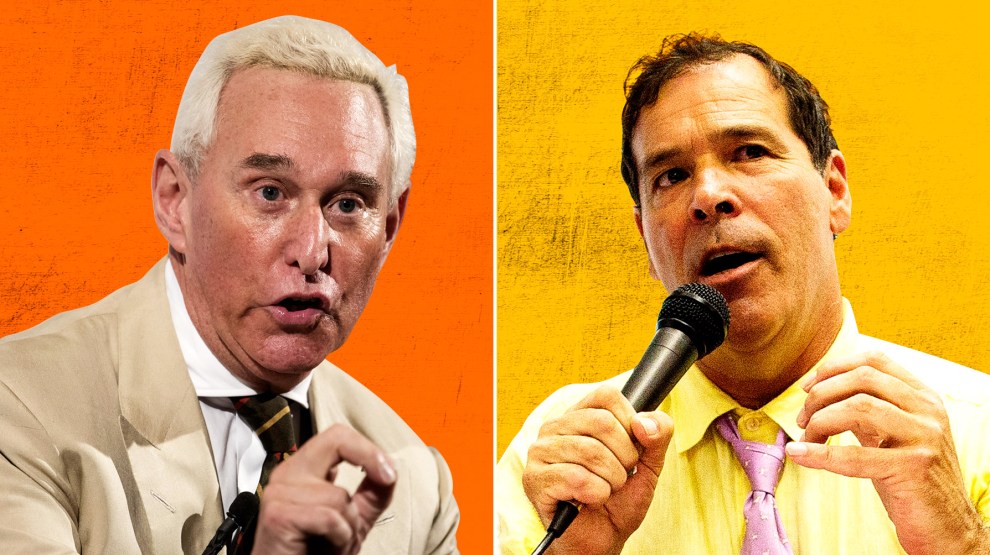

Roger Stone (left) and Randy CredicoMichael Ares/The Palm Beach Post/ZUMA; Jacquelyn Martin/AP

In 2016, Randy Credico and Roger Stone, old associates on opposite sides of the political spectrum, were each eager to tout their access to WikiLeaks, the radical transparency group releasing tranches of emails stolen by Russian hackers from Democrats. Two years later, with special counsel Robert Mueller scrutinizing possible coordination between the Trump campaign and Russia, both men are just as eager to disavow having possessed any special knowledge of WikiLeaks’ plans.

Credico, in interviews with Mother Jones, claims that in 2016 he “bullshitted” Stone into thinking that he was in contact with WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and his inner circle. And Stone maintains that his own comments during the campaign, in which he said he had “communicated” with Assange and appeared to accurately predict WikiLeaks’ anti-Clinton releases, were nothing more than “posture, bluff, [and] hype.” The pair have meanwhile spent the past year accusing each other of lying about their interactions in the final months of the 2016 election. Stone says much of his information on WikiLeaks came from Credico. Credico denies that. What really happened is hard to know, but the difficult task of separating the facts from the BS in the messy Stone-Credico melodrama has fallen to Mueller. In the end, Stone and Credico may have indeed concocted or exaggerated their claims of inside access—but their efforts to appear in-the-know could nevertheless lead to serious consequences.

During the 2016 campaign, Stone’s strident tweets and statements implying knowledge of what WikiLeaks was up to buttressed his reputation as a plugged-in political trickster. (He also insisted that the Russians had nothing to do with the Democratic National Committee hack, echoing and amplifying Kremlin disinformation.) But after Donald Trump won an unexpected victory and US intelligence agencies concluded Russian intelligence had hacked Democrats and passed material to WikiLeaks in a bid to help Trump, Stone’s comments became a problem: possible evidence that he had a hand in coordinating the release of the stolen documents.

Appearing before the House Intelligence Committee in September 2017, Stone shifted his story. He said he had merely feigned familiarity with Assange’s plans, relying on guesswork and a WikiLeaks intermediary that his lawyer eventually identified to the panel as Credico.

A New York-based comic and left-leaning political activist, Credico was a die-hard WikiLeaks supporter who hosted a radio show that Assange appeared on as a guest. He also was close with Margaret Ratner Kunstler, a lawyer who represented Assange’s group. Credico and Stone had formed an unlikely political friendship in 2002 when they both backed the independent gubernatorial bid of Tom Golisano in New York. They were allies of sorts again during the 2016 campaign: A backer of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and, after his primary loss, Green Party candidate Jill Stein, Credico shared Stone’s desire to harm Hillary Clinton’s heavily favored campaign.

Credico has strenuously denied he was Stone’s source. But that claim came into question earlier this month when NBC News reported on a series of texts Credico exchanged with Stone during the final months of the 2016 election. The messages, in which Credico stated that WikiLeaks was poised to release damaging material on Clinton, seem to support Stone’s contention that Credico offered him information on WikiLeaks.

Yet prior to these text communications with Credico, Stone had already publicly asserted he had inside knowledge of WikiLeaks. And he appears to have had another source, right-wing conspiracy theorist Jerome Corsi. On Tuesday, NBC News reported that Corsi sent an email to Stone on August 2, 2016, to say that he had learned that WikiLeaks planned two upcoming document dumps, the second in October. The email is cited in a draft court document that Mueller’s team shared with Corsi. The document says Corsi lied to federal prosecutors by claiming he had rejected Stone’s request that he contact WikiLeaks to obtain information about its plans to release hacked Democratic emails. Corsi, too, has claimed publicly that he merely deduced WikiLeaks’ plans without inside information. “I was probably pumping myself up in an email,” Corsi told the Washington Post. (Stone told NBC that his correspondence with Corsi does not “provide any evidence or proof that I knew in advance about the source or content of any of the allegedly stolen or allegedly hacked emails published by WikiLeaks.”)

Credico, in response to the report on his texts with Stone, now tells Mother Jones that he misled Stone, saying he “bullshitted” the Republican operative into thinking he had access to WikiLeaks that he actually lacked. That claim resembles Stone’s current story that he faked inside knowledge of WikiLeaks. That is, both men now contend they were dissembling. That may be true, but even if so, the bragging has still landed Stone in Mueller’s crosshairs. Stone may yet be charged for some role in the email dump, but even if he isn’t, Mueller is reportedly investigating him for obstruction of justice and perjury. Credico also faces consequences for his role in all this—at least legal fees and public attacks. But he insists he spoke honestly when he appeared before Mueller’s grand jury and has no legal worries.

According to Stone, he released his texts with Credico now—instead of months earlier, when Credico began disputing his account—because his attorneys recently extracted the communications from an old phone. Spanning late August to early October 2016, the texts, which Stone’s lawyer, Grant Smith, provided to Mother Jones, do not represent all the texts that passed between the men in that period. Smith says he excluded “everyday stuff” unrelated to WikiLeaks. (Credico says the texts are presented out of context, but he declined to elaborate.)

“Julian Assange has kryptonite on Hillary,” Credico wrote Stone on August 27, two days after Assange called in to Credico’s radio show. Assange phoned in from the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, where the WikiLeaks founder has taken refuge for the past six years.

A month later, on October 1, Credico texted Stone: “[B]ig news Wednesday. [N]ow pretend you don’t know me.”

“U died 5 years ago,” Stone responded, a reference to his once starting a rumor that Credico was dead.

“Hillary’s campaign will die this week,” Credico added 14 minutes later.

At the time, Credico had just returned from London, where he had planned to visit with Assange. But, Credico now says, he never made it past embassy security. Yet he led Stone to believe the visit had taken place as planned, even sending Stone selfies from outside the embassy.

“I was playing with him,” Credico tells Mother Jones. “I didn’t have anything. I was a spectator like he was.”

“It was pure bullshit talk,” Credico adds, noting that he only knew that Assange had suggested in late July that WikiLeaks planned to release more information on Clinton before Election Day. “I bluffed and guessed.”

On Sunday October 2, 2016, shortly after hearing from Credico, Stone tweeted, “Wednesday@HillaryClinton is done. #WikiLeaks.” But October 5 came and went without news from WikiLeaks. Still Stone publicly professed confidence. “Libs thinking Assange will stand down are wishful thinking,” he tweeted. “Payload coming.”

But privately Stone “was wigging out,” according to Credico, who recalls Stone was bombarding him with questions about the delay. Stone “called up screaming, ‘How come they haven’t put anything out?’” Credico says. Credico was critical of Clinton’s hawkish foreign policy views, and he says Stone tried to play on that, repeatedly asking, “Do you want a war with Russia?”

“He was frantic,” Credico notes. “I’ve never seen him like that.”

“What the fuck do you want me to do about it?” Credico says he replied. He maintains he had had no way to influence WikiLeaks’ timing and did not try.

Stone did not respond to questions about those alleged phone calls.

On Friday, October 7, WikiLeaks finally released a trove of emails hacked from Clinton campaign manager John Podesta, dumping them 30 minutes after the Washington Post published the Access Hollywood video in which Trump boasted of grabbing women “by the pussy.”

When Trump won the election, seemingly aided by WikiLeaks’ releases, Stone and Credico’s alleged access to WikiLeaks became liabilities. Each was subpoenaed by the House Intelligence Committee. Credico, who says Stone urged him not to cooperate with the panel, asserted his Fifth Amendment right to decline to testify. And as he was drawn into the Russia scandal, Credico privately lashed out at Stone for dragging him into a legal morass. He was saddled with legal bills and had trouble finding work with progressive organizations repelled by his apparent role in the controversy.

Messages that Credico has provided to Mother Jones show that Stone at first tried to assuage Credico, at one point offering to help Credico raise money to cover his legal expenses and telling him that he was working to get the Trump administration to issue a “blanket pardon” for Assange. Stone’s messages to Credico also show he was eager to stop Credico from publicly disputing his description of Credico as his back channel to WikiLeaks. (Stone says this is because his claim was true.)

But as Credico began publicly contradicting Stone’s account in media interviews, the Republican operative grew increasingly combative, sending Credico a string of menacing text messages. “Prepare to die cock sucker,” Stone wrote in one email to Credico this spring.

Meanwhile, the special counsel’s focus on Stone appeared to intensify. Mueller summoned more than a dozen Stone associates for interviews or grand jury testimony. Among them was Credico, who appeared before the grand jury in September. Credico has met several times with Mueller’s investigators, and he is scheduled to sit down with them again next week.

In August, Mother Jones reported that Mueller was reviewing Stone’s emails to Credico. Several publications have since reported that Mueller’s investigators are examining whether Stone’s missives amounted to witness tampering or obstruction of justice. Stone insists he merely urged Credico to tell the truth. But in an obstruction case, threatening messages as well as inducements—such as offering help with legal fees or a pardon for Assange—could be seen as an effort to influence a witness.

Mueller is also reportedly examining whether Stone perjured himself during his House Intelligence Committee testimony. Rep. Adam Schiff, (D-Calif.), who is set to become chairman of the committee in January, said recently that “some of [Stone’s] answers before our committee are highly suspect.” Schiff has said he plans to ask the Justice Department to prosecute witnesses he believes misled the committee.

Stone, who denies lying to the panel, says it is Credico who should be worried. He claims that if Credico told the grand jury what he has said publicly—that he was not Stone’s back channel—he is the one who could face perjury charges. “Everyone should be demanding answers from Mr. Credico as to why he lied over and over again,” Smith, Stone’s lawyer, said in an email. Yet Credico says he stands by his grand jury testimony and asserts that Stone lied to the Intelligence Committee.

Who is telling the truth? Maybe neither.