RichLegg/Getty

In Louisiana, defendants charged with a felony can be sent to prison for life—even if the entire jury doesn’t agree on whether or not to convict. But on Tuesday, residents will have an opportunity to change that by voting on Amendment 2, a measure that seeks to require unanimous juries.

“How can you say a person has been convicted and found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt when one or two of the jurors says, ‘No, I have reasonable doubt,'” Ed Tarpley, a former district attorney in Grant Parish and advocate for the measure, asked during a session of the Louisiana state legislature this spring.

As Mother Jones previously reported, the non-unanimous jury law has had a long history in the state:

Louisiana’s jury law is more than 100 years old and a remnant of the Jim Crow era, when the newfound political power of freed slaves created panic among whites and laws reinstating social and government control over black people were enacted in droves. Louisiana lawmakers who pushed for the measure’s inclusion in the state constitution in 1898 said it would resolve the problems created by allowing black people to serve on juries, calling it an effort “to establish the supremacy of the white race…to the extent to which it could be legally and constitutionally done.” Soon before the current state constitution was ratified in 1974, there was an effort to repeal the jury rule, but it lost traction.

Louisiana has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country and a disproportionate number of inmates are people of color.

Supporters of the amendment, who include Republicans and Democrats, say unanimous juries are the bedrock of the criminal justice system. “It’s the unanimous jury of 12 citizens that makes a decision about whether to deprive someone of their liberty,” said Tarpley, “It’s a powerful protection we have in our government.”

However, the state’s Republican Attorney General Jeff Landry has come out against the measure. His deputy, Bill Stiles, says the AG’s office believes the non-unanimous jury law has had a “positive effect” on the criminal justice system because it allows for more efficiency. Stiles told the New Orleans Advocate that the system is especially effective because it prevents someone from trying to sway a jury. “We live in an era where some people think everything a cop does is wrong,” he said. “Anecdotally, I’ve had cases where people are on video committing a crime, and a juror says, ‘I can’t convict this person.'”

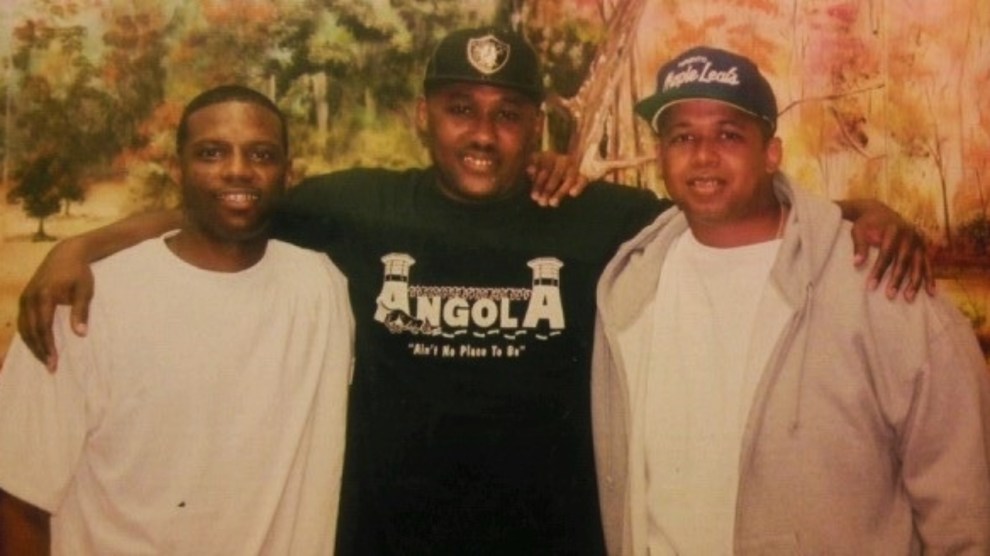

But for the previously incarcerated, the system has been anything but positive. In 1974, Norris Henderson was convicted of second-degree murder and sent to prison for life after a jury voted 10 to 2. Henderson has maintained his innocence and in 2003 was released by a judge after spending nearly 30 years behind bars. Today, he is fighting to get Amendment 2 passed. “This would literally change what mass incarceration looks like in Louisiana,” he told the Times-Picayune. “Truly, this is Jim Crow’s last stand.”