Melody Hart speaks to Ansly Damus via webcam at the Geauga County Safety Center.Courtesy of Gary Benjamin and Melody Hart

Somewhere in an Ohio jail, Ansly Damus was listening to Melody Hart and Gary Benjamin. It was late October, and they were telling Damus that the trees were changing colors. Damus, a 42–year-old asylum-seeker from Haiti, had not been allowed outside in two years.

Hart and Benjamin, a local married couple in their sixties who had become Damus’ biggest allies and advocates in the United States, didn’t know exactly where Damus was. They’d been making the hour-long drive from Cleveland to visit Damus in the small town of Chardon nearly every week for the past nine months, but they’d never actually seen him face to face. Inmates in the Geauga County jail must speak to friends and family through webcams and small monitors. Hart and Benjamin were sitting in a narrow room with 10 screens. As they talked to Damus, a timer on Benjamin’s cell phone counted down from 30 minutes, after which the video line would be cut.

Damus mentioned that his eight-year-old daughter back in Haiti had asked him for a tablet. Damus, of course, had no way to send one; he couldn’t even call her or mail her letters. But Hart and Benjamin said they had an extra tablet and promised to send it to her. As on all their visits, their goal was to lift his spirits. It was not an easy task. He lived in a windowless room from which he could not see the sun or the moon. As the visit wrapped up, they reassured Damus that they would pray for him and his quick release.

Back in July 2016, when he started his journey to America, he imagined that upon arriving at the border, he would spend three days in government custody before being released. Instead, he was sent to a county jail in Ohio, a state he had no connection to or intention to visit. In Haiti, Damus had taught ethics at a professional school and math and physics to middle schoolers but said he fled in 2014 after a local gang beat him for criticizing a corrupt politician. He first traveled to Brazil and later began a robbery-plagued, three-month trek across the Americas before finally arriving at the border in California in late 2016.

There, he did exactly what US immigration officials have consistently told asylum-seekers to do: He came to an official port of entry and asked for protection from the persecution he’d faced back home, and a judge granted him asylum. What’s happened to him since is an extreme illustration of the distortion of the asylum process under President Donald Trump. US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, under its new Trump-appointed leadership, appealed Damus’ asylum decision, and while the case was being heard, ICE kept him locked up in Chardon. After the judge upheld his asylum grant, ICE again appealed, and Damus remained at the jail. The prolonged incarceration was emblematic of an administration that does everything in its power to keep asylum-seekers in jail, rather than releasing them with ankle monitors or other forms of supervision.

And so Damus languished in the jail, a mild-mannered former teacher among criminals, for three months, then six. For one year, then two. All the while, he was never allowed to step outside for recreation. Criminals in the jail were sometimes allowed to leave for work, but Damus, as an ICE detainee, was not. Until he started using an elaborate system, he couldn’t even communicate with his family.

When Hart and Benjamin left the jail, Damus returned to his cell, where he faced the prospect of many more weeks or months in confinement—if he wasn’t deported first.

Damus arrived at the Calexico, California, border crossing two weeks before Trump was elected president. It was the end of a two-year journey from Haiti. He initially lived in a refugee camp in Brazil before finding short-term work as an electrician and construction worker. After about 18 months, he traveled overland to Peru and Colombia, where he was robbed for the first time. He journeyed through Central America with a group of about 50 migrants from Cuba, Benin, Nepal, and elsewhere. In Nicaragua, he was robbed again during a three-week trek through the mountains. In Guatemala, he had to bribe the police to continue north.

In October 2016, he arrived at the California border and went to the port of entry in Calexico, a small town more than 100 miles east of San Diego. US and international law protect migrants’ right to request asylum, and Trump administration officials have repeatedly urged asylum-seekers to go to ports of entry. Once in the United States, Damus was quickly transferred to the Geauga County jail to await his asylum hearing.

The entrance to the Geauga County jail in Chardon, Ohio.

Noah Lanard

Shortly before Trump took office, ICE denied Damus’ first parole request, on the grounds that he was a flight risk because he lacked sufficient community ties. For the next year, Damus was on his own, aside from assistance from his Ohio immigration lawyer, Elizabeth Ford. Convicted criminals came and went as he lived in the windowless room that held 20 prisoners and, to him, felt saturated with carbon dioxide. Each day brought the same routine: Lights on at 6, head count, breakfast at 7, dinner at 5, head count, lights out at 11. He was humiliated, ashamed, and cut off from his wife and two young children in Haiti. International calls and letters were not allowed. For hope, he returned to a passage from the Book of Hebrews that assures that “discipline always seems painful…at the time, but later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness.” For strength, he turned to Job, who bore burdens even greater than his.

Eighty-six percent of Haitians were denied asylum between 2012 and 2017. Yet in April 2017, Cleveland immigration judge Alison Brown granted Damus asylum. ICE made the rare decision to appeal Damus’ asylum grant and kept him in jail while the case was considered by the Board of Immigration Appeals, a division of the Justice Department. The appeals board sided with ICE and ordered Brown to reconsider parts of her decision. She granted Damus asylum for the second time in January 2018. ICE appealed again. Damus had now been in jail for 14 months, and there was no end in sight. Damus compared his experience to showing up at someone’s home and asking for help. America let him in and then treated him like a robber, he said.

ICE has long detained more people than its detention centers can hold, but under Trump, the number of detainees has shot up to record highs. ICE has let far fewer asylum-seekers out of detention, while also targeting long-settled undocumented immigrants who spend more time in detention because they have strong cases for remaining in the United States and are less likely to be deported quickly. As a result, it has expanded its capacity at both dedicated immigration detention centers and local jails it pays to hold immigrants. The Geauga County jail gets $70 per day per immigrant from ICE, or more than $25,000 per year, according to ICE records from 2017. The average number of immigrants at the jail more than doubled between 2014 and 2018, from 28 to 76 in a facility with a total capacity of 182. Nationally, ICE held roughly 14,500 migrants at more than 170 city and county jails in 2018—more than a third of the agency’s inmates. All across the country were people like Damus who’d followed the legal procedures to seek asylum and ended up isolated in jail cells in places where they’d never planned to be.

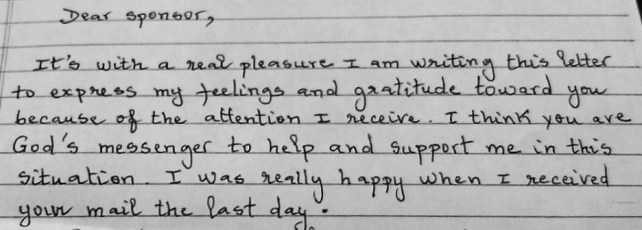

Ford, working pro bono, put together a second parole application after Damus was awarded asylum a second time in January and ICE again appealed. She tried to head off ICE’s claim that Damus lacked community ties by getting a local family to offer to house him. Through Anne Hill, an immigration activist, Ford got in touch with Hart and Benjamin. They immediately agreed to sponsor Damus, even though they had never met him. “We are empty nesters and have a large home,” they wrote in a letter to ICE, in which they listed their professional qualifications: Benjamin was a lawyer and Hart was an accountant.

Later that month, Damus heard an announcement over the jail’s intercom: “Damus visit.” He thought it was a mistake and didn’t respond. Then he heard it again. He went over to the monitors and saw what he described as two white faces. He couldn’t communicate much with Hart and Benjamin during that first visit. He barely spoke English, and Benjamin knew only rudimentary French, but they eventually found ways to understand each other. Hart and Benjamin wrote Damus three letters a week in French, with the help of Google Translate, and mapped out uplifting conversations in advance of their weekly Sunday visits. Damus was often on the verge of giving up and voluntarily allowing himself to be deported back to Haiti. Their goal was to keep him fighting. Chantal Dothey, a doctor who had moved to Ohio from Belgium, visited him on Friday nights after hearing about his case from Hill.

ICE policy requires the agency to assess each parole request individually and consider the facts of the case. ICE denied Damus’ parole request one day after Ford sent in the paperwork, even though he’d been granted asylum and ICE’s appeal was pending. Government data later showed that ICE’s Detroit field office, which covers Ohio, denied almost every asylum-seeker’s parole application in the first months of the Trump administration. This was happening across the country, in a trend that started in the Obama administration but accelerated dramatically under Trump. In five field offices including Detroit, the average rate of parole approvals dropped from 92 percent between 2011 and 2013 to less than 4 percent between February and September 2017, even though ICE claimed its parole policy had not changed.

In early February, Damus met with Freda Levenson, the legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio, about a potential lawsuit. Along with Damus’ charm and character, Levenson was struck by the food he was served. “It was this pallid, pale, indistinguishable, undefinable gunk with this thin mush over it,” she said.

“He did everything according to the law,” Levenson later said. “Every single thing right. The person that broke the law here was the government. He was the innocent party.” In March, the ACLU, Human Rights First, and the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies filed a class-action lawsuit challenging ICE’s blanket parole denials, with Damus as the named plaintiff.

“I have not been outside for more than a year,” Damus said in a March court declaration. “I have not even glimpsed natural light. I have not breathed fresh air or felt the sun on my face, and I never know if it is cold or hot outside, if the sun is out, and if the seasons are changing.” Since his detention, Damus said, he had been “unbearably sad, uncomfortable and totally lacking in privacy.”

Damus’ case applies specifically to asylum-seekers who enter the United States legally. Currently, asylum-seekers who enter the United States without authorization have an easier path to getting out of confinement. They can be granted bond by immigration judges, who are generally more willing to release them than ICE, which makes the determination for people who come to official ports of entry. The Justice Department is expected to announce a change imminently that will require all immigrants to get parole from ICE, which would place all asylum-seekers in Damus’ position.

As Damus’ cases inched forward, Hart and Benjamin contrived an improbable line of communication between Damus and his family in Haiti. Their bishop got in touch with his church’s national headquarters and learned of an upcoming trip to Haiti. Damus wrote a letter to his wife, Adeline, and a church member hand-delivered it. A slightly simpler process emerged after Dothey found Damus’ wife on Facebook. Damus wrote letters and mailed them to Hart, who scanned and emailed them to Adeline. Hart would then print and mail the response to Damus. She saved Damus’ original letters in the hopes of giving them to him if he got out.

The jail didn’t allow Damus to make international calls, but Coralie Saint-Louis, a volunteer interpreter for the nonprofit Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti, made it possible by having Damus call her and patching him through to his wife back home. Hart and Benjamin tried to give Damus books in French, but the jail said donations for individual inmates were not allowed. They settled on photocopying books and mailing them 20 pages at a time, the maximum length for a letter. Damus asked for a French version of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.

Damus’ best hope of being released came over the summer, when the federal judge hearing the class-action case ruled that ICE had to follow its parole guidelines and give due consideration to each application. Ford put together a third parole application, this time with letters from a dozen community members including a local judge, a city councilwoman, and clergy. ICE sent an official to meet with Damus, then denied him parole a third time. Ford didn’t hesitate when asked if ICE had made a good-faith effort to evaluate Damus’ request. “Oh, no, they’re not seriously considering this,” she told me, adding, “That’s ridiculous.”

An excerpt of Benjamin and Hart’s second letter to ICE offering to sponsor Damus.

The ACLU focuses on forcing systemic changes and rarely takes individual cases. It made an exception for Damus. Two ACLU attorneys demanded Damus’ release in a September letter to ICE and made clear that he was willing to wear an ankle monitor. After ICE ignored the letter, the ACLU brought a lawsuit to demand that a federal judge release Damus. It was the first time Ford had ever had such a lawsuit filed on behalf of one of her clients, and she thought it was a longshot.

Then came another setback: Brown, the immigration judge, denied Damus asylum at his third hearing after the Board of Immigration Appeals overturned his second asylum grant. Now Damus was the one who had to appeal. But he had lost hope and planned to go back to Haiti. Saint-Louis, who provided moral support along with language interpretation, persuaded him to keep going. After the call with her, he cried.

Damus had grown wary of life in the United States when we first spoke in October. Back in Haiti, an American doctor had told him the United States needed professionals like him, and he took it to heart. Now he said that if he were ever released, he would be afraid of Americans he encountered in the outside world. One of his cellmates had problems with drugs and frequently talked in his sleep. “It’s inexplicable, it’s unacceptable, and intolerable,” Damus said about his incarceration. He felt that the years he had lost to jail were his biggest failure in life.

Outside the jail, Hart, Benjamin, and dozens of Ohioans, who called themselves Ansly’s Army, were protesting ICE’s decision to keep Damus incarcerated. They held rallies and prayer vigils with ministers outside ICE’s Cleveland office on Thursdays, on one occasion attracting nearly 60 people. The police once observed them with a German Shepherd in tow, though there was no need for it. “We’re all geriatrics,” Benjamin joked. Each person carried a different letter of a sign that read “Free Ansly.”

Later in October, Dothey drove out past the strip malls and country roads that lead to the Geauga County jail. As usual, she slid her ID under a two-way mirror and told an invisible official she was there to visit Damus. Inside the visitation room, Damus’ features were washed out on the monitor beneath a webcam encased in the beige plastic of outdated electronics, although his striped prison uniform was clearly visible. Damus did most of the talking, in French, while Dothey listened. She was his first visitor since he had reached two years of incarceration earlier that week. “Two years in the US,” he told me dejectedly in English. “Two years in the US.” He added that he felt bad all the time these days. His hearing in the ACLU’s suit to get him released was still three months away, and there was little to look forward to. The screen flashed off for a second to warn that the visit was almost over. One minute later, it read, “No Signal.”

The empty room Benjamin and Hart kept ready for Damus.

Noah Lanard

Two days after Dothey’s visit, Hart and Benjamin were tabling in support of Damus at church. Hart told a church group about a meeting of Ansly’s Army later that day and then headed to the jail to visit Damus. The meeting of his supporters took place at Hart and Benjamin’s Cleveland Heights home, a seven-bedroom 1915 Tudor. Molly Brudnick, a 82-year-old retired social worker, captured the mood in the room. “No matter what we do,” she said, “no matter what the ACLU does, no matter what his attorney does, we still have Ansly in jail for no reason other than the absolute power of ICE.” Most of the half-dozen people in the room had not been involved in immigration activism before Trump took office. The meeting pointed to what may be one of Trump’s most lasting and unintentional legacies: an organized progressive base attuned to the injustices of modern immigration enforcement.

The next day, a federal judge moved up Damus’ January hearing to November 28. The judge, Judith Levy, ordered that Damus appear at the hearing. The government asked if a video conference would suffice, but Levy responded that no, he would need to come in person. Damus would be wearing civilian clothes for the first time since getting to the border. Levenson, the ACLU attorney, was feeling increasingly optimistic. But Ford, who had been with Damus through all his disappointments, thought there was no way Levy would rule in Damus’ favor.

On November 28, Hart, Benjamin, and about 30 others piled onto a chartered bus for the three-hour drive from Cleveland Heights to the federal courthouse in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Damus showed up in the courtroom shackled at the legs, and Levy immediately ordered that the shackles be removed. During a recess, Hart and Benjamin hugged Damus for the first time. Levy decided she needed more information to make a ruling and ordered a follow-up call the next day. Damus spent the night in jail in Detroit. He couldn’t sleep and decided that if the court declined to release him, he would give up and go back to Haiti.

Before the call, the government told the ACLU it was willing to settle. It would release Damus if he agreed to wear an ankle monitor and live with his sponsors, the same conditions the ACLU and Damus had agreed to in September. Ford got a call from an ICE officer asking her to arrange for someone to pick up Damus at the Cleveland ICE office in one hour. She called Hart and Benjamin. “Call me when he’s in the car,” she told them. “When you have him in the car, then I’ll know it’s true.”

Last Friday, 768 days after he was first detained, Damus walked out of the Cleveland ICE office as a free man. He wore a dark suit and a white shirt buttoned to the top without a tie, and he beamed. “I want go to church,” Damus told reporters in English. “Tell God, ‘Thank you.’ He give me my life.” That night, Damus and Ansly’s Army celebrated at the Hart-Benjamin house with steak and champagne. On Saturday, Hart and Benjamin got him set up with a phone, email address, and a library card. Sunday was church—two masses and many more hugs—and a tour of downtown Cleveland. And throughout it all, many calls home. Since leaving for Brazil, Damus had missed his son’s first, second, third, and fourth birthdays. Had ICE not appealed his asylum grant, he would have already been able to apply for his family to join him in the United States.

Damus speaks to members of Ansly’s Army at the party celebrating his release.

Courtesy of Benjamin and Hart

Damus had his first quiet morning on Tuesday. He’d been surprised to see how often Americans eat in restaurants and was still looking forward to a home-cooked Haitian meal of rice, beans, and chicken. He was happier and more spirited than I’d ever heard him.

But his prospects are still daunting. Now that he is out of detention, his case will likely be a lower priority for the Board of Immigration Appeals. Hart and Benjamin have been told to be prepared to have Damus living with them for two years. The Board of Immigration Appeals has ruled against him twice, and there is reason to believe it will do so again. That would force him either to appeal to a federal court or to accept deportation.

But after so much hardship, everyone is enjoying a rare period of respite, even if it is mixed with the sadness of knowing that Damus lost two years of his life. “When you think about it, it’s just kind of sick that we can be happy about this,” Levenson said. “Because it’s misery ending.”

Unlike so many people who have been incarcerated by ICE, Damus is still in America. He plans to put his experience in jail to good use. On Tuesday, he spoke to an immigrant advocacy group about his time in Geauga County. He had received cards from the group but thought they came from an individual and expected to talk to one person. When he arrived and saw the night’s program, he was surprised to find that he was speaking to a crowd of about 30. As at every turn in his saga, he had more support behind him than he could have foreseen.

Damus at a dinner at Hart’s son’s home after his release from jail. Courtesy of Benjamin and Hart